commentarY

Tisha B'Av: Facing Our Traumas

For the Jewish people, summer brings the anniversary of our greatest national trauma. On Tisha B’Av, we don't simply mourn the loss of a building—we grieve the pain of divine abandonment. As Lamentations (the megillah or scroll customarily read on Tisha B'Av) asks: “Eicha?” or “How?—how could all this happen?”

Tisha B’Av 5781

by Yahnatan Lasko, Beth Messiah Congregation, Montgomery Village, MD

“Tell me about the most traumatic thing that ever happened to you.”

I was seated on the couch. Across from me sat a counselor. His question surprised me not with how personal it was, but because of how quickly its answer would usher him into the heart of my personal pain, fears, and struggles.

Some of us have been blessed with relatively trauma-free lives. But others have experienced a trauma in our past. It may have been a betrayal by a loved one, or perhaps a tragic accident. In the midst of these painful circumstances, we may even question God: “How could you let this happen?”

For the Jewish people, summer brings the anniversary of our greatest national trauma. On Tisha B’Av, we don't simply mourn the loss of a building—we grieve the pain of divine abandonment. As Lamentations (the megillah customarily read on Tisha B'Av) asks: “Eicha?” or “How?—how could all this happen?”

Like the garden He laid waste His dwelling,

destroyed His appointed meeting place.

Adonai has caused moed and Shabbat

to be forgotten in Zion.

In the indignation of His anger

He spurned king and kohen.

The Lord rejected His altar,

despised His Sanctuary.

He has delivered the walls of her citadels

into the hand of the enemy.

They raised a shout in the house of Adonai

as if it were the day of a moed. (Lam 2:6–7)

The author's pain is palpable:

How can I admonish you?

To what can I compare you,

O daughter of Jerusalem?

To what can I liken you, so that I might console you,

O virgin daughter of Zion?

For your wound is as deep as the sea!

Who can heal you? (Lam 2:13)

The poem of the ensuing chapter contains a confession of Israel’s own liability for the Temple’s destruction: "We have sinned and rebelled, and you have not forgiven” (Lam 3:42). The sages of the Talmud similarly acknowledged Israel’s role in bringing about the destruction of the Second Temple:

But why was the second Sanctuary destroyed, seeing that in its time they were occupying themselves with Torah, mitzvot, and gemilut chasidim [the practice of charity]? It fell because of sinat chinam [hatred without cause]. (Yoma 9b)

Given all this pain and loss, sin and judgment, is it surprising that we find Messiah at the center? Forty years before the destruction of that Second Temple, Yeshua came into Jerusalem and pronounced words of judgment over the city and its temple. These pronouncements came from Messiah not in triumph, but rather in a deep lament:

O Jerusalem, Jerusalem who kills the prophets and stones those sent to her! How often I longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing! Look, your house is left to you desolate! (Matt 23: 37–38)

Just a few days later, Yeshua himself experienced divine abandonment in the most profound sense. Hanging on a cross, he uttered his last words, according to Matthew’s and Mark’s accounts: “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?”—”My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (Matt 27:46, Mark 15:34). With his last cry, Yeshua prophetically binds himself to the impending divine judgment he himself prophesied, going ahead of the Jewish people into exile.

What is your greatest trauma? Have you struggled at times, asking God, “Where were you when this happened to me?” Perhaps you try to minimize the pain by avoiding the memory altogether, yet still it haunts you, rushing in at unexpected times.

We can try to numb ourselves, but ignoring traumas won’t make them go away. Difficult as it may be, only facing our traumas enables us to truly hear words of comfort such as those of Isaiah 53:4: “Surely he . . . carried our sorrows.”

Facing trauma is just as necessary corporately as it is individually. As the apostle Paul wrote to the Yeshua-believing community in Corinth, “Godly sorrow brings repentance, which leads to salvation” (2 Cor 7:10 NIV). By entering into the trans-generational sorrow of our people on Tisha B’Av, we not only position ourselves to truly hear God’s words of comfort, but we also help to sustain the tradition of godly sorrow, hastening the day when all Israel will receive Messiah and his Spirit of comfort. If you are a gentile, you are not only enjoined to mourn together with Israel (Rom 12:15b); you are also uniquely able to fulfill key elements of Israel's consolation as written in the Prophets (Isa 60:1–16; 61:5, 9).

So as we approach Tisha B’Av this year, let these words of Yeshua guide us: “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.”

This article first appeared in the Summer 2010 UMJC Twenties Newsletter. All Scripture references, unless otherwise noted, are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

How to Rebuke with Respect

If you love someone, honor them, even at your own expense. Get in the habit of safeguarding others’ honor and reputation. The starting point for this is being in touch with your own infinite value; only one who is secure in their place, who has “reputation to give,” as it were, is able to guard others’ honor generously.

Parashat Devarim, Deuteronomy 1:1–3:22

David Nichol, Congregation Ruach Israel, Boston

One of my favorite aspects of the Jewish interpretive tradition is the mileage the sages get out of the text of Tanakh. I recently heard Rabbi Ethan Tucker compare the way the rabbis of the midrash read the Torah to how one might read a love letter. A lover who receives a letter from their beloved will find meaning in the placement of a comma or an unusual word choice. If we read the Torah as a letter from God, the more lovesick we are, the more we read meaning into every pregnant pause, unconventional spelling, and unexpected phrasing. The rabbis of the midrash exemplify this approach, seeming to say, if we yearn deeply to hear the voice of God, we take even little details of the text very seriously; we read not just between the lines, but between every letter.

So it’s no surprise that the midrash finds something of note in the very first verse of Parashat Devarim:

These are the words that Moses spoke to all Israel across the Jordan—in the wilderness, in the Arabah opposite Suph, between Paran and Tophel, Laban, Hazeroth and Di-Zahab. (Deut 1:1)

It begins, “V’eleh hadevarim asher diber Moshe el kol Yisra’el,” “These are the words which Moses addressed to all Israel...” Immediately we might ask, why does it not just start with vayomer Moshe, “Moses said…,” or vaydaber el kol Yisra’el, “Moses spoke to all Israel”? Why does it start with, “These are the words”?

Of course, the sages asked the same question. Rashi, following the midrash (Sifrei Devarim) and targums (ancient Aramaic translations of Tanakh), reads “words” here as “words of rebuke.” After all, the midrash reasons, look at other uses of davar/devarim (“word/words”) in Tanakh. Many of those usages precede a rebuke or admonition, such as Amos 1 (“The words of Amos…”), Jeremiah 7 (“The word which came to Jeremiah...”), and others.

So if the (seemingly extraneous) use of devarim/words in the passage indicates rebuke, where is this rebuke? Read in full, Rashi’s comment explains:

Because these are words of reproof and he is enumerating here all the places where they provoked God to anger, therefore he suppresses all mention of the matters in which they sinned and refers to them only by a mere allusion contained in the names of these places out of regard for Israel [or “for the honor of Israel”].

It is the place names themselves that include the rebuke. Where Moses seems to be just listing a bunch of place names, he’s in fact alluding to the events that happened there. It’s like when I remind my wife about the late-night stop at the service area near Rochester, NY, on a car trip to Michigan. I don’t need to add, “You know, when both kids were vomiting in their car seats.” Believe me, she remembers. So the Israelites presumably cringe at the mention of these places.

This raises the question: why not be more explicit? Everybody knows what happened! Why does the text not just spell it out? Why not just say it? The first verse could have been like this:

These are the words which Moses spoke with all Israel beyond the Jordan, reproving them because they had sinned in the wilderness, and had provoked the Lord to anger on the plains over against the Sea of Suph, in Pharan, where they scorned the manna; and in Hazeroth, where they provoked to anger on account of flesh, and because they had made the golden calf.

In fact, that’s exactly how it’s rendered by the ancient Aramaic translation, Targum Onkelos (~4th century CE). However, the text of the Torah is much more subtle, not mentioning these specific events at all.

I propose two reasons that Moses might be circumspect with respect to Israel’s sins in the wilderness. First, the dignity of humans is a central Jewish value; conversely, public humiliation is a serious offense. The Talmud underscores the seriousness by stating that “anyone who humiliates another in public, it is as though he were spilling blood” (Bava Metzia 58b). Quoted above, Rashi attributes the circumspection to God’s concern for Israel’s honor or glory.

This leads us to ask why God is so concerned about Israel’s honor. Certainly human dignity is important; according to the Talmud, guarding the dignity of another takes precedence even over the observance of a prohibition in Torah (Berakhot 19b). But even more fundamentally, God loves Israel, and we care about the honor of those we love. “When Israel was a youth I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son” (Hos 11:1).

The second reason is more practical. This speech from Moses isn’t about dwelling on the past. The sins of Israel aren’t decisive enough to fracture the relationship. No, Israel has a mission, a shelichut, something to accomplish. Just a few verses later, God tells the people that it’s time to get moving: “You have stayed long enough at this mountain. Turn, journey on…” (1:6). It’s been forty years, and it’s not the time for rehashing old arguments, or bringing up failures of the past. That would be a distraction from the task at hand.

We can learn lessons from both of these reasons.

If you love someone, honor them, even at your own expense. Get in the habit of safeguarding others’ honor and reputation. The starting point for this is being in touch with your own infinite value; only one who is secure in their place, who has “reputation to give,” as it were, is able to guard others’ honor generously. Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe put it well:

The beginning of all individual work is specifically the experience of man’s exaltedness. Anyone who has never focused on man’s exaltedness from his very creation, and whose only self-work is to know more and more about the bad sides of himself and to make himself suffer as a result—that person will sink deeper and deeper into despair, and in the end, will make peace with the bad out of sheer lack of hope of ever changing it. (Alei Shur, vol 1)

But our insecurities are in vain, since our value is beyond measure! As Yeshua said, “Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them shall fall to the ground apart from your Father’s consent. But even the hairs of your head are all numbered. So do not fear; you are worth more than many sparrows” (Matthew 10:30-31).

Once you are confident in your own value, you become free to turn toward reminding those you love of their intrinsic worth.

And who hasn’t rehashed old arguments, allowing themselves to focus on their own anger or unresolved feelings of betrayal, processing their own anger in the guise of rebuking another? There is always a temptation to reach into the bag and bring out old offenses, recycling the weapons that once hurt you, to hurl them back at their original owner. But to do so is rarely helpful.

I find this to be particularly relevant as a parent. Certainly some of the “rebukes” directed toward my children are for the sake of their edification and growth. But all of them? Hardly. Sometimes it’s more about me than about what is best for them.

On the other hand Moses seems to anticipate Paul’s words: “Let no harmful word come out of your mouth, but only what is beneficial for building others up according to the need, so that it gives grace to those who hear it” (Eph 4:29).

And so in one verse, we find deep teachings about how to relate to each other by imitating the Creator. May he strengthen our hands to preserve each other’s honor, and when we must rebuke, to do so in proper measure, and out of love.

Individualism Meets Responsibility

The concept of individualism tempered by participation in the collective whole has been challenged this past year, as the emphasis on individuals and their rights seems to have skyrocketed. The problem is that individualism apart from participation in the collective whole leads to chaos.

Parashat Matot-Masei, Numbers 30:2–36:13

Dr. Vered Hillel, Netanya, Israel

Right action tends to be defined in terms of general individual rights and standards that have been critically examined and agreed upon by the whole society. —Lawrence Kohlberg, American psychologist known for his theory on the stages of moral development

The concept of individualism tempered by participation in the collective whole has been challenged this past year, as the emphasis on individuals and their rights seems to have skyrocketed. The problem is that individualism apart from participation in the collective whole leads to chaos. For example, see the closing verse of the book of Judges (21:25): “In those days there was no king in Israel. Everyone did what was right in his own eyes.” But when individual uniqueness and rights are tempered in relationship to the collective whole, orderliness and harmony abound.

This week’s Torah portion exemplifies Kohlberg’s statement, as it demonstrates the intertwining of the rights, actions, and situations of individuals with the needs of the collective whole. Our parasha concludes the Book of Numbers, which records the final segments of Israel’s journey from Egypt to the land of Canaan. It ends with the children of Israel standing on the banks of the Jordan River in Moab, ready to cross into the Promised Land. The forty-two places Israel encamped during their forty-year period of wandering in the wilderness are recorded in Numbers 33:1–49. This itinerary points out that the Jewish people were on a real, historical, flesh-and-blood journey and also reveals things about B’nei Israel’s spiritual journey, about their relationship with Adonai and the calling they would embody once in the Promised Land. Hashem planned and directed Israel’s every move. He declared his mercies and compassion, as well as his great love for his chosen people, throughout the adventure. During the journey, Hashem taught Israel to love and fear him and to trust and appreciate the security, love, and care he provides. The itinerary demonstrates Hashem’s love and care for the community as a whole.

In last week’s parasha, Pinchas, we saw Hashem’s love, care, and justice for individuals through the story of Zelophehad’s daughters (Num 27:1–7). This week’s parasha picks up the saga of Zelophehad’s daughters in the final verses of both the parasha and the Book of Numbers (36:1–13). When read together, the two parts of the daughters’ story illustrate the importance of individuals being an active part of a collective whole, meaning a tribe, people-group, or society.

In part one, Zelophehad’s daughters approached Moses and the leaders of the children of Israel requesting the right to inherit their deceased father’s land allotment, since there were no sons (Num 27:1–7). The sisters requested their rights as individuals, not as a group. They were individuals who needed to be treated according to their uniqueness and particularities, including their extraordinary situation; no previously-given legislation or precedent existed upon which to base a decision. So Moses, as was his pattern, took the matter to Hashem, who recognized the justice of the sisters’ cause and granted their request. This incident demonstrates the importance of Hashem’s love and care for individuals and that each person’s unique identity, rights, and situations are particular to them.

Part two of the story tempers the rights of the individual with that of the collective whole. The leaders of Zelophehad’s clan approached Moses and the leaders of the children of Israel, just as the daughters had done. The clan leadership objected to the daughter’s inheritance of their father’s land. The leaders rightly claimed that if the daughters were to marry outside of the tribe of Manasseh, the land would automatically pass to the husband’s tribe, thereby depriving the tribe of Manasseh of its land inheritance. Here again there was no legislation or precedent upon which to judge the request. Moses took the request to Hashem, who recognized the justice of the leaders’ request. As a result, Moses decreed that Zelophehad’s daughters must marry within the tribe of Manasseh, which is exactly what the young women did; they married their first cousins, their father’s nephews. The complete story of Zelophehad’s daughters, part 1 and part 2, teaches us the importance of balancing our individual uniqueness, situations, and rights with the larger collective whole.

The importance of balancing individual uniqueness and rights with the good of the collective whole is also seen in the request by Reuben and Gad to settle in the conquered territory on the east-side of the Jordan River (Num 32:1–38). Initially Moses emphatically rejected their request, but after subsequent discussion a compromise was reached. Moses conceded to the request of the two tribes with the stipulation that they would cross the Jordan River and battle alongside the children of Israel until every tribe was settled in the land of inheritance. The tribes of Gad and Reuben initially spoke from their individuality as a tribe, without regard for B’nei Israel as a whole. They were looking out for themselves; their highest priority was their wealth and prosperity, and their own comfort and future. These two tribes only consented to help all of the children of Israel settle in the land after their negotiations with Moses and their acceptance of his stipulations. The tribes of Gad and Reuben received their individual requests, in essence establishing their individual rights. At the same time, these individual requests were tempered by the demand for the two tribes to fight alongside all of Israel until the entire community was settled in the land of Canaan. Three clans from the tribe of Manasseh also settled on the east side of the Jordan River. However, they never requested this privilege, nor were they given any stipulations as were the tribes of Gad and Reuven. First, it seems that the land allotted to the tribe of Manasseh on the east side of the Jordan falls within the territorial boundaries of the children of Israel as outlined in Numbers chapter 34, so it was already designated as part of their inheritance. Second, the other half of the tribe of Manasseh settled in the Land of Canaan, choosing to join the collective whole of Israel, whereas Gad and Reuben did not.

We are currently in the three weeks of repentance before Tisha B’Av. Let us use this time to reflect on how our individual uniqueness can be tempered in light of our participation in the People of God, our communities, society, and countries. Remember Peter’s exhortation, “you like living stones are being built together into a spiritual house” (1 Pet 2:5).

Chazak, chazak, v’nitchazek! Be strong, be strong, and let us be strengthened!

Illustration from https://www.fruitfullyliving.com/.

Jerusalem the Waiting Bride

The words of Jeremiah the prophet draw our attention beyond our undeniable failures as a people to our equally undeniable foundation as a people chosen and loved by God. And it’s particularly striking that the Lord is speaking here specifically to Jerusalem.

The First Haftarah of Affliction, Jeremiah 1:1–2:3

Rabbi Russ Resnik

The words of Jeremiah, the son of Hilkiah . . . to whom the word of the Lord came in the days of Josiah the son of Amon, king of Judah . . . until the end of the eleventh year of Zedekiah, the son of Josiah, king of Judah, until the captivity of Jerusalem in the fifth month. (Jeremiah 1:1–3)

The fifth month of the Hebrew calendar is Av, and on its ninth day, Tisha b’Av, 586 BCE, the holy temple was destroyed by the Chaldeans, launching what Jeremiah describes starkly as “the captivity of Jerusalem.” For three weeks leading up to this mournful day, we read passages from the prophets, the Haftarot of Affliction, beginning with Jeremiah chapter 1.

Jeremiah describes his calling from God, who set him apart from before birth as a prophet to bring a message warning of judgment to come, along with a hint of hope:

Behold, I have put my words in your mouth.

See, I have set you this day over nations and over kingdoms,

to pluck up and to break down,

to destroy and to overthrow,

to build and to plant. (Jer 1:9b–10)

Jewish tradition doesn’t ignore the warnings of judgment, and we recognize the past judgment on Tisha b’Av each year, but our tradition teaches us to also look for the note of hope—“to build and to plant.” And so the reading for this week concludes with the first three verses of Jeremiah 2:

The word of the Lord came to me, saying, “Go and proclaim in the hearing of Jerusalem, Thus says the Lord,

“I remember the devotion of your youth,

your love as a bride,

how you followed me in the wilderness,

in a land not sown.

Israel was holy to the Lord,

the firstfruits of his harvest.”

This lovely vision pictures Hashem’s romance with Israel, who followed him out of Egypt and into the wilderness like a bride devoted to her husband. The prophet’s words draw our attention beyond our undeniable failures as a people to our equally undeniable foundation as a people chosen and loved by God. And it’s particularly striking that Hashem is speaking here specifically to Jerusalem. Jerusalem didn’t literally follow him in the wilderness and had no apparent role in the narrative of redemption from Egypt at all. Yet, by Jeremiah’s time, Jerusalem represents the soul of the people Israel, so that her story and Israel’s story are deeply intertwined.

. . .

In the days of his earthly ministry, Messiah Yeshua looked ahead to another Tisha b’Av—the date of a second destruction of the temple, this time by Rome, in 70 CE. On his way to Jerusalem for his final Passover, Yeshua is well aware of his coming crucifixion, and yet even more troubled by the crucifixion of Jerusalem that will come not long afterwards. Some Pharisees have warned him that Herod, ruler of Galilee, is seeking to kill him, so he’d better move on, and Yeshua replies,

Go and tell that fox . . . “It cannot be that a prophet should perish away from Jerusalem.” O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing! Behold, your house is forsaken. And I tell you, you will not see me until you say, “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!” (Luke 13:32–35)

The last two verses here (13:34–35) appear also in Matthew 23:37–39, but in a different context. In Matthew, Yeshua says these words not on the way to Jerusalem, as in Luke, but after his triumphal entry into the city when the crowds had called out, “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!” (Matt 21:9). In Matthew’s version, therefore, the promise “you will not see me” contains an additional word—“again” (Matt 23:39). This minor detail suggests that Matthew sees the triumphal entry as a prophetic enactment of Yeshua’s future return, when Jerusalem will see him “again” and this time cry out “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!”

There’s another difference in the two accounts. In Matthew 23:37, Yeshua says to Jerusalem “you were not willing” after having a number of disputes with the Jerusalem authorities (Matt 21:10–22:46). In Luke’s version, however, Yeshua says “you will not see me” before he has even arrived in Jerusalem, and before he has tested Jerusalem’s “willingness” to respond.

How then do we interpret Yeshua’s sadness at Jerusalem’s rebuff, apparently before it even happens? How can Yeshua claim that the city “will not see” him, shortly before he shows up and is seen there? Yeshua seems to be acting here as a prophet speaking God’s own words in the name of God. As commentator Robert Tannehill argues, the words “how often have I desired to gather you” (Luke 13:34) refer to “the long history of God’s dealing with Jerusalem,” and the words “you will not see me” likewise refer not to Yeshua, but to God: “Verse 35 is speaking of the departure of Jerusalem’s divine protector, who will not return to Jerusalem until it is willing to welcome its Messiah, ‘the one who comes in the name of the Lord.’”

This interpretation brings Luke 13 into harmony with our first Haftarah of Affliction, Jeremiah 1:1–2:3. In Luke’s account, the longing for Jerusalem’s welcoming response belongs not only to Yeshua but even more to God, whose love for the city and whose grief at its wickedness is not a recent development but has extended through multiple generations, as Jeremiah also reveals. Accordingly, the predominant tone of Yeshua’s words here is one of lament. Nevertheless, a more positive note emerges in the end: “You will not see me until you say, ‘Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!’” (Luke 13:35, emphasis added). We have reason to hope that the divine presence, whose departure renders the city vulnerable to its enemies (“Behold, your house is forsaken”), will return again, to comfort and glorify Jerusalem.

The condition for such a future return is clear: the city—apparently still in its character as the capital of the Jewish people—must offer the same welcome to the Messiah that he will receive from his Galilean followers later in Luke’s account, when he enters the city a few days before Passover.

Yeshua’s crucifixion during Passover sets the stage for his resurrection on the third day. It also expresses Yeshua’s identification with Jerusalem, which will endure a similar fate at the hands of Rome a generation later—and will be resurrected when Messiah returns. Crucifixion bears the seed of resurrection to come. Tisha b’Av is a day of mournful remembrance, but also a day of hope.

But let’s seek not only hope for the future but also guidance for life today in the words of Jeremiah and Messiah Yeshua, in the way they both speak of Jerusalem. Hashem chooses to address his people not in abstract or generic terms, but in intimate terms as Jerusalem his bride. Yeshua verbalizes God’s intimate longing to gather Jerusalem’s children under his wings. They both remind us to pay attention to the living, breathing, impassioned person near us, to not turn persons into objects, either of our admiration or, perhaps more commonly, of our disdain. God looks at a face and remembers a story even as he warns of judgment to come. We can do something similar amid our everyday encounters, as we treat others with kindness and dignity. Thus we can have hope not only for the future redemption, sure to come, but also for redemptive human interaction while we await it.

Portions of this drash are adapted from Besorah: The Resurrection of Jerusalem and the Healing of a Fractured Gospel, by Mark Kinzer and Russ Resnik. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2021.

Scripture references are from the ESV.

Almost a Prophet

Like a play within a play, the episode with Balaam confronts us with a truly paradoxical figure: a God-fearer who could prophetically proclaim the rise of Israel but dies merely a soothsayer, almost as a passing footnote.

Parashat Balak, Numbers 22:2–25:9

Ben Volman, Kehillat Eytz Chaim, Toronto

Like a play within a play, the episode with Balaam (or as in the CJB, Bilam) confronts us with a truly paradoxical figure: a God-fearer who could prophetically proclaim the rise of Israel but dies merely a soothsayer, almost as a passing footnote. Strangely enough, the rabbis actually refer to this lengthy interlude as “the book of Balaam.” In his day, Balaam must have been of great repute. Yet in this sidra featuring his four great oracles, he’s portrayed with a mixture of honor and comic relief. Even with the long shadow cast by his prophecies, the rabbis generally give him short shrift.

It all begins with an offer from Balak, the Moabite king, that he was sure Balaam could not refuse: a lavish fortune to place curses on Israel. It was an era when armies had professional sorcerers to curse their enemies, but Balaam’s original answer suggests an unexpected spiritual depth from this gentile: “Even if Balak were to give me his palace filled with silver and gold, I cannot go beyond the word of Adonai my God to do anything, great or small” (22:18).

Though warned by God to only do what God has allowed (v. 20), an unsuspecting Balaam has incurred the Lord’s wrath. While urging his donkey toward the rendezvous with Balak, he’s riding into the drawn sword of the Angel of the Lord. The master may be blind, but the donkey isn’t. The beast, acting as the true “seer” is only the first of several humiliations.

Under Balaam’s repeated furious beating, the donkey that saved his life speaks up. Perhaps we can explain this not as the voice of the donkey, but more the ventriloquist work of the Lord. The irony is fully played out when the master angrily yells at his donkey he wishes he had a sword to kill it just as his eyes are opened to the death-wielding Angel.

Balaam seems truly chastened. And his relationship with the Lord appears genuine enough to earnestly speak the words ba’al peh, placed in his mouth. Rashi is not impressed, however, and thinks that the description of God making himself manifest to Balaam (va-yikar—literally “he fell in”) suggests a lesser relationship than God had with true prophets.

Still, the poetry is not just impressive, but resonates through history, as in, “a people that will dwell alone / and not think itself one of the nations” (23:9). This description of Israel as distinctively separate is now almost taken as doctrine in a common worldview divided between Jew and gentile. And there’s brilliant word-play: “May I die as the righteous die!” with “righteous” translated from y’sharim—echoing the name of Israel, Y’shurun (23:10).

When his original plan fails, Balak presses the seer to try another spot for cursing. Balaam can only proclaim: “Look, I am ordered to bless; / when he blesses, I can’t reverse it. / . . . Adonai their God is with them / and acclaimed as king among them” (23:20–21). As for the Israel that Balaam elaborately depicts with the strength and power of a lion and a lioness—we barely recognize that people, which has been struggling since they left Egypt, resisting God, arguing with Moshe, and complaining the full length of the desert. Now they’re praised as fully worthy of blessing: “How lovely are your tents, Ya‘akov; / your encampments, Isra’el!” (24:5).

Balak urges Balaam to stop, “Don’t curse and don’t bless.” Instead, Balaam will prophesy of Israel’s coming dominance: “They shall devour enemy nations” (24:8). Finally, there is a promise that will again resonate for centuries as a promise identified with Messiah, and applied by Rabbi Akiva in the second century CE to Bar Kochba: “I behold him, but not soon — / a star will step forth from Ya‘akov, / a scepter will arise from Isra’el” (24:17ff.).

An infuriated Balak tells the seer that he’s never getting that promised wealth, and instead receives Balaam’s prophecies of the “last days” against Israel’s enemies. When they part ways, the rabbis interpret the place to which Balaam returned (li’m’kmo, his place) to mean “hell” (Mishnah Par. 3:5).

But we will see him again. In Numbers 31 we learn that Balaam set a trap for the men of Israel, seducing them to the immoral worship and prostitutes that please the Ba’al gods of fertility. Except that Balaam’s cleverly covert ways have finally led to his ruin—and he is slain with Israel’s enemies at Midian.

That’s not the last word on him, by any means. He’ll be repudiated later in Deuteronomy, then Joshua, Nehemiah, Micah, and on into the B’rit Chadashah, including this condemnation by Peter (Kefa): “These people have left the straight way and wandered off to follow the way of Bil‘am Ben-B‘or, who loved the wages of doing harm but was rebuked for his sin” (2 Peter 2:15–16).

Was he a real prophet or a gifted soothsayer? The Talmud suggests that he began as a true prophet, but abandoned the faith for gain—so that the original oracles were authentic, but these were to him like a “fishhook” from which he struggled to break free (Sanh. 105a–106b).

Another surprise—his name is written into fragments of writing on a plastered wall in an ancient Temple in Deir’Alla, Jordan (about 70 kms north of the Dead Sea). This unique archaeological find recounts a strange vision of the notable seer clearly identified as “Bal’am son of Be’or.” Again we’re reminded, this man must have been a notable figure in his day.

“Absolute power corrupts absolutely,” but most of us are corrupted with much more gradual, incremental steps off the moral track. Despite all of Balaam’s public pieties, after the bribes of Balak, others must have come, perhaps more generous. Finally, the seer’s weakest impulses apparently prevailed. Who knows what excuses he gave himself?

No figure so fully brings to life the warning of Yeshua,

Not everyone who says to me, “Lord, Lord!” will enter the Kingdom of Heaven . . . On that Day, many will say to me, “Lord, Lord! Didn’t we prophesy in your name? . . . Didn’t we perform many miracles in your name?” Then I will tell them to their faces, “I never knew you!” (Matt 7:21–23)

One has to wonder—might he not have been so much more? After the Lord whom he recognized as the true God had revealed the significance of Israel and the blessings they were under, why did Balaam align himself with God’s enemies? The brilliant Franz Rosenzweig, who was about to become a follower of Yeshua, but declined after a Yom Kippur service in which he dedicated himself to Judaism, has another suggestion. Balaam’s error, he says, “was not taking God at his first words: ‘Do not go with them.’ Because the next time God will without fail speak the words of the demon that is within us—‘You may go.’” And there, but for the grace of God, go you and I.

All Scripture references are from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

Buy a Ticket Already!

Everyone knows that simply looking at something cannot cure a deadly snakebite. What healed the Israelites was the power of God, through their display of faith in looking at the serpent raised up by Moses. It’s a testament to God’s character that, despite the lack of faith shown by the Israelites again and again, once they repented, he gave them a means to display faith in him once more, and by it, be saved from certain death.

Parashat Chukat: Numbers 19:1–22:1

Chaim Dauermann, Simchat Yisrael, West Haven, CT

Here’s an old joke you’ve probably heard before: A man desperately wants to win the lottery, as he knows it will solve his profound financial troubles. Every night, he prays to God, asking him to grant him this one, simple request. However, after weeks and weeks of praying, he has not won the lottery, and eventually he becomes despondent. In his anguish, he cries out to God, asking why he has not yet won. In response, a booming voice sounds from the heavens: “So buy a ticket already!” It’s just a joke, but the lesson is a good one: getting help from God doesn’t mean that nothing will be required of us.

All throughout the Torah record, God is revealing himself to humanity, teaching us about who he is. Many of these events have become formative and foundational tales in our culture: Noah’s ark, the crossing of the Red Sea, the Ten Plagues, and the story of Sodom and Gomorrah are but a well-known few. But this week’s parashah, Chukat, features one story about God that would be easy to miss if we didn’t know where to look for it, just one tiny anecdote tucked amidst the more significant-seeming beats of the wider narrative: the story of the bronze serpent.

One thing that the Torah’s wilderness narrative makes clear is that the children of Israel excelled at complaining, and Parashat Chukat is no exception. In Numbers 20, the children of Israel had complained mightily of their lack of water, and in response, God gave Moses some instructions for what to do. He told him merely to tell the rock to provide, but Moses took things a step further, out of his own frustration, and struck the rock with his staff. Although God was ultimately displeased with him, it did not prevent abundant water from gushing forth. There was more than enough to satisfy the needs of the Israelites.

But then, in the next chapter, we hear of yet more grumbling from the children of Israel: “And the people spoke against God and against Moses, ‘Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we loathe this worthless food’” (Num 21:5).

The food they no doubt referred to was the manna they had in abundance, which by the power of God fell from the sky six days a week (with a double portion before the sabbath) to fulfill all of their nutritional needs. God had delivered them from slavery, provided them food and water time and time again, and had led them to the land he had promised them—which they had failed to enter, out of their own fear—yet still they complained. God was not slow to respond: “Then the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died” (Num 21:6). Desperate for relief, the people appealed to Moses, “‘We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord and against you. Pray to the Lord, that he take away the serpents from us.’ So Moses prayed for the people” (Num 21:7).

Although the Bible is mum on the exact meaning of “fiery serpent,” it’s generally understood to be a poisonous snake. (Some have put an even finer point on things, and surmised that these were saw-scaled vipers—snakes which remain plentiful throughout the Middle East, and are the most dangerous in the world. Even today, no anti-venom exists to treat their bite.) Whatever these fiery serpents were, God had a peculiar prescription for relief of their venom: “And the Lord said to Moses, ‘Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.’ So Moses made a bronze serpent and set it on a pole. And if a serpent bit anyone, he would look at the bronze serpent and live” (Num 21:8–9).

Now, anyone knows that simply looking at something, whether a bronze serpent or anything else, cannot cure a deadly snakebite. What healed the Israelites was the power of God, through their display of faith in looking at the serpent raised up by Moses. It’s a testament to God’s character that, despite the lack of faith shown by the Israelites again and again, once they repented, he gave them a means to display faith in him once more, and by it, be saved from certain death. This particular story is instructive because of what it tells us about the nature of God and the redemption he offers us. To put a finer point on it: It’s instructive about the faith he requires of us.

Upon hearing the good news about Yeshua, it’s easy for some to react in an incredulous manner. Just believe, and we are saved? Why would God do something like that? Though it may seem peculiar at first hearing, it is not outside the pattern of God’s character, as we see the exact same process modeled for us, on a smaller scale, in this passage in Chukat: instead of a snake’s venom, think of sin; instead of a bronze model of a serpent, think of the Messiah. In the wilderness, God provided redemption to the children of Israel through the likeness of that which was killing them. So, too, could it be said of his provision of Messiah: “By sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin, he condemned sin in the flesh” (Rom 8:3b).

For the Israelites in the wilderness, it was not quite so simple as looking at the snake and being healed: They had to first repent before God provided them with an antidote to the venom, in the form of the bronze serpent. And then, when looking upon the serpent, they had to believe they would be healed. So, too, must we do when it comes to Messiah: “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9). Or, as Yeshua himself said: “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matt 4:17b).

Perhaps the most famous gospel passage in the world is John 3:16: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.” These words of Yeshua testify to the pure and simple gospel message. But it is easier to understand the reality this passage portrays if we keep in mind what Yeshua says in the two verses preceding it: “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life” (John 3:14–15).

If we are ready to repent, God is ready to save us. All that remains left to do is buy a ticket.

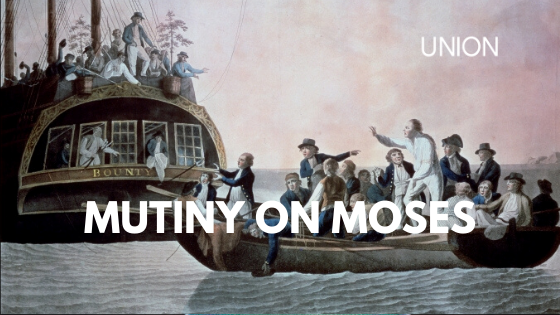

Mutiny on Moses

Ever heard the title Mutiny on the Bounty? On April 28, 1789, Lieutenant Fletcher Christian seized control of HMS Bounty, and set Captain William Bligh adrift in a small boat on the open sea. I mention it here, because we’re looking at one of the Hebrew Bible’s versions of a mutiny—in this case, against Moses not Bligh.

Parashat Korach, Numbers 16:1-18:32

by Dr. Jeffrey Seif

Ever heard the title Mutiny on the Bounty? On April 28, 1789, Lieutenant Fletcher Christian seized control of HMS Bounty, and set Captain William Bligh adrift in a small boat on the open sea. I mention it here, because we’re looking at one of the Hebrew Bible’s versions of a mutiny—in this case, against Moses not Bligh.

This week we’re told Korach (or Korah) “rose up against Moses” (16:1–2a). It wasn’t simply a personal dispute, however. It was political. With a mind to put checks on Moses’ authority, and garner more and more authority for himself and his associates, Korach “took two hundred and fifty men” with him, all of whom were “men of renown” (16:2). “You’ve gone too far! All the community is holy—all of them—and Adonai is with them,” was their battle cry. “Who do you think you are, Moses?” they exclaimed, and “We don’t need you telling us what to do” (paraphrase). The charge closes with a question: “Why do you exalt yourself above the assembly of Adonai?” (16:3). Sounds like a mutiny to me—on the open sand, not the open sea.

The HMS Bounty left England in 1787. The crew had a five-month layover in Tahiti, during which time they settled in and co-mingled with the islanders. Crew members became lax, prompting the captain to impose disciplines on his crew—adjudged to be his prerogative. Chagrined by Bligh’s (mis)management, Lt. Christian rebelled, and the better part of the crew with him. T’was a mutiny! As noted, Captain Bligh was put off on a small boat and set adrift on the open seas. That was Bligh’s situation. What of Moses’ back-story?

Moses had been walking down a rough stretch of highway for some time, before Korach actually took him on. In Numbers 10:11, the people left Sinai and disembarked for Canaan. In 11:1ff, their kvetching over lack of provisions invoked Moses’ ire. In 12:1-2, Moses’ sister Miriam expressed chagrin over her sister-in-law, Moses’ wife. Aaron was drawn into her consternation, and together they uttered a comment that appears later—on the lips of Korach: “Has Adonai spoken only through Moses? Hasn’t he also spoken through us?” (12:2). The Hebrews were restless while en-route to Canaan, and it only got worse when they arrived. Our last parasha, Sh’lach l’cha, told how a reconnaissance mission into Canaan, launched from Kadesh-Barnea, turned into a feasibility study—one with dire consequences (Num 13:1ff). Spies assessed Canaan, and returned with various pieces of information. The spies processed the data but offered unsolicited advice along with it: “we cannot attack these people because, they are stronger than we,” was the upshot of their report (13:31). In sum, Israelites were disconcerted by circumstances they happened upon en-route to Canaan, and they were chagrined by their prospects for success in a soon-coming war with the intimidating Canaanites. “Enough already!” was Korach’s response. He and others believed political change was necessary.

I’ve never commanded a sea-faring vessel, and I’ve never led multiple hundreds of thousands of people through a wilderness. For my part, I’ve been involved in religious leadership for over thirty years. Incessantly taken aback by pressures and problems associated with the rabbinic or pastoral office, I’ve forever read myself as Moses in the Korach story, and Korach and his associates as vociferous associates disinclined to follow my lead. In sum, I refracted the narrative through the prism of my experience and used it to tacitly justify myself and vilify my detractors. Perhaps you have too. Is that fair, though?

Though there are congregational applications, to be sure, the problem I have with reading the passage through my experience now is that it betrays a core hermeneutical principle I hammered as a seminary professor for years: the first interpretation of a passage belongs to the first recipients of it—not the exegete. This is axiomatic. Never mind my context. What was Moses’ context?

Moses wasn’t a rabbi or a reverend attending to the personal one-on-one spiritual needs of one or two hundred people. He wasn’t a religious therapist/counselor. Moses wasn’t tasked with responsibilities associated with building communal consensus to chart paths forward, either. Congregational boards wrestle direction, personnel issues and expenditures, and interact with rabbis and reverends to get it all done. Unlike the reverends and rabbis and boards of today, Moses of yesterday was something of a political leader—much as he was a religious leader. The Mosaic economy he brought forth had a juridical component, one that dealt with a host of criminal and civil mandates. Reverends and rabbis have power to suggest a course of action—not demand it; Moses did, and he actually had power to even effect a death sentence. The Mosaic code imposed mandatory tax burdens, too, in order to support the Levites who were vested with responsibility to manage Israel’s civil affairs and oversee its criminal ones. Rabbis and reverends politely ask for a buck; Moses’ code taxed for it. The ancient world was driven by an agrarian economy, one regulated tightly in the Torah by various Mosaic promulgations. Do reverends, rabbis and boards regulate congregants’ economies? I think not. Some thought Moses took too much power. Korach said as much. Might you have thought or said so, too?

Alighting upon political issues as I close, and not pastoral ones, I am wondering if God’s people would do well to be a bit more respectful toward legitimate, political leaders. My reading of Korach prompts applications to congregational life, to be sure—it can’t help but do that. It also prompts me to advocate for better civil discourse and responsibility, reminding me that we do well to respect those in authority—and so heed the words of the Rabbi from Tarsus, who beckoned us to do just that (Rom. 13:1–7).

This commentary first appeared on UMJC.org, June 21, 2017.

All Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

Monsters, Giants, and Other Formidable Obstacles

The fears, horrors, and insecurities of our childhoods do not disappear with time, as we might imagine, but rather remain buried deep in our psyche only to reemerge in more sophisticated expressions. Unless we slay, shrink, or unmask the monsters and giants of our past, they make a home next to our “child within.”

Parashat Sh’lach L’cha, Numbers 13:1–15:41

Paul L. Saal, Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

I originally wrote this d’var Torah in 2008. I cannot remember what fears I felt forced to confront then, but somehow this commentary feels every bit as relevant today. Much has been said about the fears we faced as we went into quarantine or semi-lockdown mode. But 15 months later we deal with a totally different set of fears on the way out. To vaccinate or not to vaccinate; going back to the office, school, or even synagogue; what are the correct procedures and protocols? And the greatest fear of all, putting on my hard clothes that fit last year. The one thing that has not changed is the nature of fear itself. So, I hope this drash offers some perspective and some hope!

In the spring of 2002, I went to an art exhibit featuring a group of pictures painted by a good friend who was beginning the process of leaving the safety of a career as a commercial artist and pursuing an art form that was uniquely his own. The collection was entitled quite simply, “Monsters.” I was not prepared for the transition in his work. My friend’s commercial work had always been clean, crisp, and professional and uncluttered. His new art was dark, convoluted, layered and primitive, obscuring warm colors with dark shadows.

What my friend had done was to take his seven-year-old son’s crayon drawings of monsters and reinterpret them in a more adult, almost surrealist genre. The oil re-creations hung next to the crayon originals in this sophisticated Massachusetts gallery. Though there was no written explanation of the work, it communicated to me an honest, yet often ignored reality of life. The fears, horrors, and insecurities of our childhoods do not disappear with time, as we might imagine, but rather remain buried deep in our psyche only to reemerge in more sophisticated genres and expressions. Unless we deal with, slay, shrink, or unmask the monsters and giants of our past, they make a home next to our “child within.”

Giants of Old and Now

The Torah portion this week begins with Moses sending out twelve agents, one from each tribe, to examine the land and give a report to the people. They all reported that the land was a good land that did indeed “flow with milk and honey” (Num 13:28). But ten of the twelve tribes saw only the potential for calamity in the land and could not imagine that the God who had guided them to this land might also deliver it into their hands. Their report is very telling: “we looked like grasshoppers to ourselves, as so we must have looked to them” (13:33). What is even more telling is the reaction of most of the people, who wept all night and complained about their leaders, imagining that they would have all been better off staying in Egypt. In fact, they even contemplated heading back to Egypt. In their minds they were still slaves, undeserving of freedom.

On the surface their reaction seems so illogical that it would have been not only silly but also improbable. Of course, their lives in Egypt were a 400-year living hell—beatings, starvation, thankless labor, and often-unceremonious deaths at the hands of ruthless masters. Yet how can we explain that even today, in the midst of our “enlightened” society, there are those who remain under the thumb of abject abuse? Wives and children who are regularly beaten, employees who stay in thankless underpaid jobs, and devotees who remain in systems of spiritual abuse, exhibit the same tendency to endure the hardship of the known, rather than face the giants and monsters that loom so large in their imagination.

In stark contrast though, the spies of our Haftarah portion, Joshua 2:1–24, give us a renewed sense of hope. They went into Jericho after forty years of wandering and came out with a completely opposite opinion to their predecessors: “Truly the Lord has delivered into our hands all of the land; and moreover all of the inhabitants of the land melt before us” (Josh 2:24). What happened from one generation to the next? How did they conquer their fear? They spent forty years observing that an unseen force nurtured, protected, and preserved them. They came to believe that the God who had delivered them from bondage for the sake of their fathers, and who had promised them the land they were about to enter, could and would bring it to pass. The fact is, fear is to courage as inhaling is to exhaling. It is hope, though, that gives us the courage to do what we are afraid to do. We fear and we hope at the same time; and fear lurks behind hope, just as the bright face of the moon hides its dark side.

The Many Faces of Courage

Courage has multiple faces. It can mean saying no to compromise, or it can mean making a difficult compromise. It can entail dying a heroic death or living through terrible pain. It can mean fighting a good fight or knowing when it is best for all to concede. But courage always involves facing our fears.

Having courage often means enduring when troubles are upon us. Morrie Schwartz exemplifies this passive kind of courage as recorded in the book Tuesdays with Morrie, by Mitch Albom. Morrie was Mitch’s beloved professor with whom he had kept in sporadic contact. But when Morrie became terminally ill Mitch decided to visit him with regularity. The book documents their every Tuesday meetings and Morrie’s rapid physical decline. But as his condition declined his inner courage became more evident.

The Children of Israel certainly endured much torment during the years of enslavement. Much is made of their lapses of faith and mutinous activities, but not enough is spoken of Israel’s emerging courage. In large measure Israel endured despite endless foes and constant threat to their survival, and so it continues today. Through inquisition, holocaust, pogrom, and jihad, Israel has grown in its passive courage.

But active courage is also essential. This requires us to act well at the risk of danger. We look our fears full in the face and do what we must in spite of it. Israel had to muster this type of courage as they prepared to enter the fortified city of Jericho. It would have been easier to find elsewhere to sojourn. After all they had livestock, and gold and treasures taken from Egypt. Weren’t they the descendants of nomads and, after all, weren’t their encampments in the wilderness vastly superior to their past life of bondage in Egypt? But that would not have allowed them to fulfill their destiny.

Ruby Bridges is no longer a household name. But when the Louisiana public schools were integrated back in the turbulent 1960s Ruby was the first little girl to cross the line and enter a previously segregated public elementary school. Having only sheriff’s deputies and State Policemen between herself and the assembly of bigots who came out to spit and hurl insults, the courageous little girl walked the gauntlet to a new school where she would have no friends, no acceptance, and no comfort. When interviewed, Ruby’s mother described why Ruby did what she did: “There’s a lot of people who talk about doing good, and a lot of people who argue about what’s good and what’s not good, but there were also some other folks who put their lives on the line for what’s right.” Active courage is no more difficult to muster than passive courage, but easier to put off. Much of our procrastination is a sluggish denial of our fears.

Oxford English Dictionary defines courage as “facing danger without fear.” This may be a popular opinion, but I think it’s patently untrue. In fact, I believe only people who are afraid truly exhibit courage. The question is, where do we get the strength to do the things we are afraid of? The answer is hope. The spies in this week’s Haftarah portion in a sense are the reconstituted courage of Caleb and Joshua, who stood up to the masses and their own monsters and giants, and believed the promises of God. Continuing a forty-year journey of monotony, pain, and suffering demanded resolve, courage, and spiritual stamina. As a result, the people of Israel were birthed in a womb of hope. God met all their needs and led them toward his promises. So, in this sense hope was their fear as seen through the lens of their courage.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a German pastor who risked everything to fight the Nazis. He was put in prison, and from there he penned letters that give people hope today. In one, he wrote this prayer: “Give me the hope that will deliver me from fear and faintheartedness.” He was given hope and hope gave him courage. The Nazis killed Bonhoeffer anyway. But his hope was not unrealized. The Nazis were defeated, and God was seen, as he always is, as the ultimate victor.

We are often afraid that we are losing the fight, and we suffer fear and anxiety. But hope brings back a faith that we will win. So, face those fears, large and small, head on, and echo the words of Rav Shaul, “I can do all things through Messiah who strengthens me” (Phil 4:13).

Faith Is Not an Easy Journey

When walking by faith, we are not guaranteed the knowledge of the “whats and whys” of our walk. Like Israel, we may not know how long that walk might be or what its various stops or detours might be like. We can have our hopes or ideas, but in all things, we must trust in Hashem.

Parashat Beha’alotcha, Numbers 8:1–12:16

by Michael Hillel, Netanya, Israel

From the time I left the bus, that muggy, dark evening on the 6th of August 1972, I learned the discipline of following orders . . . immediately. I should mention that the bus dropped me and the rest of the passengers in a debarkation area at the Recruit Training Depot, Parris Island, South Carolina. So, from the moment we stepped off the bus and onto the tarmac, we learned that when an order was given, we had to do everything we could to obey it—and whether that order made sense or not did not matter in the slightest. We also learned, fairly quickly, that the time to do said orders was immediately, and without hesitation—unless it was a time-related order like, you will be ready to go in exactly 15 minutes. This learning process continued for the next three months of basic training and then carried on for the next twelve years as I served on active duty in the United State Marine Corps.

What does this trip down memory lane have to do with this week’s parasha, you may ask? Hopefully it will become clear soon.

This week’s parasha is Beha’alotcha (“when you set up”). There are numerous items covered in this parasha, but I want to focus on Numbers 9:15–23, which begins,

On the day the Tabernacle was erected, the cloud covered the Tabernacle. By evening until morning, the cloud above the Tent of Testimony had an appearance like fire. It was that way continually. The cloud covered it, and by night it appeared like fire. (9:15–16)

This passage is reminiscent of the scene in Exodus 40 when the setup of the Tabernacle was completed, and it was consecrated.

So, Moses finished the work. Then the cloud covered the Tent of Meeting, and the glory of Adonai filled the Tabernacle. For the cloud of Adonai was on the Tabernacle by day and a fire was there by night, in the sight of all the house of Israel throughout all their journeys. (Exod 40:33–34, 38)

One can but imagine the sight this was. In the very middle of the camp and ringed by the tribe of Levi, who had charge of the Tabernacle (Num 1:50), was the visible Presence of Adonai, surrounded by the rest of the Israelites, as well as by the myriads of those who accompanied them in the Exodus. The Presence appeared either as a cloud by day or pillar of fire by night, and was seen 24/7 in the midst of Bnei-Yisrael, the people of Israel.

Now comes the connection with my little trip down memory lane:

Whenever the cloud lifted up from above the Tent, then Bnei-Yisrael would set out, and at the place where the cloud settled, there Bnei-Yisrael would encamp. At the mouth of Adonai, Bnei-Yisrael would set out, and at the mouth of Adonai they would encamp. All the days that the cloud remained over the Tabernacle; they would remain in camp. (Num 9:17–18)

It appears that Bnei-Yisrael moved, not at their own initiative but at the command of Adonai (or Hashem). The passage goes on to state that at times the camp would remain in place for many days, at other times for just a few days, and on occasion, just overnight. In the Word Bible Commentary on Numbers, Philip J. Budd rightly agrees with most other biblical commentators that, while Israel’s history was rife with episodes of obedience and disobedience, in the matter of the Tabernacle in the Wilderness they at least stayed on track. Equally, Israel’s obedience to move or not to move showed a dependence upon Hashem’s right, and even responsibility, to guide Israel through the trials of the Wilderness. I believe Budd’s most important observation, however, is that, “The movement of God, symbolized by the cloud, and God’s times may not always be subject to rational explanation. Man’s (Israel’s and our) commitment is to follow in faith” (p. 104).

But, as Israel discovered, following Hashem by faith was not an easy journey.

If any of you have ever gone camping, remember how long it took to set up your camp for the evening, or maybe for the weekend, or even an extended campout. Now multiply that by 603,550 (Num 1:46), plus wives, children, Levites, servants, livestock etc. Finally consider that if you were in that crowd of 600,000 plus, setting up camp, you had no idea if this was going to be an overnighter or if you might be there for a year or even more. With this in mind, words from the author of Hebrews become even more meaningful. “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of realities not seen” (Heb 11:1).

When walking by faith, we are not guaranteed the knowledge of the “whats and whys” of our walk. Like Israel, we may not know how long that walk might be or what its various stops or detours might be like. We can have our hopes or ideas, but in all things, we must trust in

Hashem and his guidance as we walk out life’s journey. In this life of chaos and confusion, we can hold onto these words from the Psalmist: “For this God is our God, forever and ever! He will guide us to the end” (Psa 48:14).

In this we can have the assurance that just as Hashem guided and directed Bnei Israel in the Wilderness, with all of the side trips and detours, he will guide us through the wildernesses of our lives as well. Likewise, just like Bnei-Yisrael in the Wilderness, we too should “walk by faith, not by sight” (2 Cor 5:7).

Shabbat shalom u’mevorach!

All Scripture references are from the Tree of Life version (TLV)

A Cure for Jealousy

A man becomes suspicious that his wife has been cheating on him. He has no proof, only his feelings of jealousy. So, the husband publicly accuses his wife of adultery and brings her to the temple to perform a ritual to prove her guilt.

Parashat Naso, Numbers 4:21-7:89

by Jared Eaton, Simchat Yisrael, West Haven, CT

Parshat Naso contains one of the most difficult and uncomfortable passages in the Bible: the details of the Sotah Jealousy Ritual found in Numbers 5:12–31.

A man becomes suspicious that his wife has been cheating on him. He has no proof, only his feelings of jealousy. So, the husband publicly accuses his wife of adultery and brings her to the temple to perform a ritual to prove her guilt.

The woman is brought before the priest and has her hair uncovered and loosened, not a big deal in our society, but in communities where keeping your hair covered is a sign of modesty, this is the equivalent of being stripped naked.

The husband makes an offering to God and then what almost seems like a magic spell happens. The priest fills a bowl full of holy water then mixes dirt from the temple floor into it. The priest then writes on a parchment, that if the woman has been unfaithful, then God will curse her. He will cause her belly to become swollen and her insides to rot. The woman must agree to this curse and then the priest mixes the parchment into the dirty water and then the woman has to drink the foul concoction. If the woman is guilty of adultery, then immediately the waters will become bitter inside of her and cause her to rot from the inside out. If she is pregnant with another man’s child, the child will die and she will be accursed among her people for as long as she lives, which will not likely be long. The woman will bear her guilt, but the husband will be free of guilt.

Pretty nasty stuff. Even apart from the hideous death it promises to unfaithful women, it seems so humiliating, even to the innocent.

Is this what the Bible teaches? To brutalize the weak, to treat our wives like property? To resort to superstition and mysticism when dealing out justice? Or is there something deeper going on here?

The Sotah ritual does sound like magic. It’s complex and deeply symbolic and difficult for the modern reader to wrap their head around. So, let’s imagine a contemporary situation, in which the temple still exists and biblical law is still in effect, to illustrate how the Sotah ritual as interpreted in the Talmud (b.Sotah 2a) might be used.

Meet Sara and Lenny. They have a happy marriage, but lately things have been rough. Sara works at a downtown office, and in recent months has become friendly with one of her coworkers, Bob. Sara and Bob eat lunch together every day, talk on the phone often, and have started to spend time together outside of work.

Lenny isn’t feeling good about this. He feels that Sara and Bob’s relationship is undermining his own relationship with his wife. Lenny asks his rabbi what to do and the rabbi tells him that the Talmud states that he should confront his wife about his feelings and do so in the presence of two close, trusted friends, so there will be witnesses, who can intervene in case things get heated.

Lenny takes the rabbi’s advice. In front of their friends Joe and Jane, he asks Sara to not be alone with Bob anymore. Sara agrees that she won’t see Bob anymore and the issue seems like it’s resolved, but a week later, Joe and Jane are out taking a walk and what do they see but Sara and Bob together? They follow them for a bit and to their dismay they see Sara and Bob walk into a hotel.

They feel obligated to tell Lenny what they witnessed. Lenny is distraught and asks them if they are sure; did they actually see the adulterous act? Joe and Jane have to admit that they didn’t actually witness any adulterous activity; all they saw was the opportunity for adultery.

So once again Lenny confronts his wife. He tells her what Joe and Jane saw. Sara admits, that yes, she went into the hotel with Bob, but it was only to have lunch at their restaurant. She swears that she didn’t do anything else with Bob and that she has been faithful to her husband.

Lenny and Sara are at an impasse. Lenny has good reason to be jealous. Sara continued her relationship with Bob even after her husband had asked her to end it. Sara insists that she has been faithful but doesn’t have anything other than her word to prove it. What is this couple to do?

Lenny and Sara go back to their rabbi, and he tells them that there are only two possible solutions at this point. Either they can decide to dissolve the marriage immediately, regardless of Sara’s guilt or innocence, or they can choose to re-establish a trusting relationship based on Lenny’s acceptance of his wife’s innocence.

Lenny and Sara love each other, and they don’t want to split up. But how can Lenny trust Sara now? She insists that she’s innocent but there’s no way to prove what really went on after they went into that hotel. There’s no way for Lenny to dispel his lingering doubts. Their marriage seems doomed.

But then the rabbi suggests a solution. There was a witness to what happened in the hotel he says. God! Sara’s innocence can only be attested to by God himself. “How?” they ask. So, the Rabbi tells them about the Sotah ritual.

Lenny and Sara go to the temple and the priest instructs them on how to perform the Sotah Ritual.

First, the husband has to bring an offering for his wife to demonstrate that they are participating in a mutual effort towards reconciliation.

Next, the priest takes a clay jar, and fills it with water from the sanctuary wash bin, and takes dust from the sanctified earth on which the temple stands.

Finally, the priest writes down the two possible consequences of the Sotah test. If Sara has been unfaithful to Lenny, the water will turn bitter inside her, but if she is telling the truth and has been faithful, the water will not harm her, and she will be blessed with fertility and bear children. Sarah then has to voluntarily agree to the terms of the test. If she doesn’t agree the whole test becomes invalidated.

Finally, the priest places the parchment into the jar, and the writing becomes dissolved into the water, and then comes the moment of truth.

Sarah stands before the priest and has her hair uncovered and let loose over her shoulders. It sounds unnecessarily humiliating, but the rabbis argue that this isn’t done as punishment. If it were, they would have done it in public where everyone can see. Instead, she loosens her hair only once she’s sequestered with her husband and the priest as a symbolic representation of her vulnerability and dependence on the mercy of God.

Sarah holds up the bowl to her lips and tilts it back. At that moment Lenny realizes that this all has been a huge mistake, he realizes he doesn’t care what Sara may have or have not done, she’s the love of his life and he can’t imagine life without her. He doesn’t need some crazy test to tell him that he wants to be with her forever.

Lenny leaps to knock the bowl from Sara’s hands but it’s too late, she’s already drunk the waters. Lenny stands back motionless, unable to even breathe as he waits to see what will happen to his wife. After moment, Sara grimaces and says, “That tasted awful! But otherwise, I feel… pretty good.” Lenny bursts into tears of relief and he rushes to embrace his wife. Sara has passed the test. She has proven herself a faithful woman. And the trust between her and her husband has been restored.

So, what happened here? Is the Sotah test magic? The truth is Sara was never in any danger at all. The water she drinks, while dirty, is completely harmless by itself. In order for the water to harm her, God would have to come down and perform a miracle in order to prove her guilty!

At no point in the whole process is the woman forced to do anything against her will. According to the Talmudic interpretation of the biblical text, if Lenny demanded the test and Sara didn’t want to do it, she always had the option to ask for a divorce instead. In fact, since there was no evidence that she had committed adultery, the divorce would have been considered no fault and Lenny would have to pay her alimony.

The Sotah test can only be taken voluntarily and only an innocent woman would agree to it. If Sara had really been unfaithful, she almost certainly would have taken the option of divorce rather than face the dire consequences of the test. Only a woman who still genuinely loves her husband and wants to restore his trust in her would have the courage and faith in God’s justice to take the test.

When Sara entered the temple, her reputation was in shambles. Her friends, family and coworkers wondered if she was an unfaithful wife and thought less of her for it. But when she emerges from the temple whole and unharmed, hand in hand with her husband she is vindicated before the whole community. Both her reputation and her relationship with her husband have been restored. Soon after, according to Gods promise, she and Lenny conceive their first child and continue on in their journey together.

I love a happy ending.

The great medieval scholar Ramban notes “there is nothing amidst all the ordinances of Torah that depends upon a miracle, except this matter.” In every other case, God tells us to rule amongst ourselves according to his laws. But when a marriage is threatened, God himself steps off his throne and comes down to deal with it personally.

God’s involvement in the Sotah test demonstrates the level of his presence in every marriage. The union between husband and wife and their faithfulness towards each other is a special object of Gods attention. How much more should we value that relationship ourselves?