commentarY

The Temple in the Torah and Today

As Israel stood listening to Moshe at the edge of the Promised Land, they were still a people whose greatest patriarchs had been nomads buried in a distant cave bought from strangers. So it’s unlikely they could have imagined a future temple of soaring dimensions to the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

Parashat Re’eh, Deuteronomy 11:26–16:17

by Ben Volman, Kehillat Eytz Chaim, Toronto

As Israel stood listening to Moshe at the edge of the Promised Land, they were still a people whose greatest patriarchs had been nomads buried in a distant cave bought from strangers. So it’s unlikely they could have imagined a future temple of soaring dimensions to the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob; an edifice to rival the storied palaces and temples of Pharaoh. Yet the kernel of that vision is embedded here in Devarim/Deuteronomy 12:10–12:

When you cross the Yarden and live in the land Adonai your God is having you inherit, and he gives you rest from all your surrounding enemies, so that you are living in safety; then you will bring all that I am ordering you to the place Adonai your God chooses to have his name live—your burnt offerings, sacrifices, tenths, the offering from your hand, and all your best possessions that you dedicate to Adonai; and you will rejoice in the presence of Adonai.

Rashi suggests that these verses should be understood as an instruction to build the Jerusalem Temple, based on a parallel reference to the words indicating that Israel was “at rest” from its enemies under King David. He quotes 2 Samuel 7:1–2: “After the king had been living in his palace awhile and Adonai had given him rest from all his surrounding enemies, the king said to Natan the prophet, ‘Here, I’m living in a cedar-wood palace; but the ark of God is kept in a tent!’”

Indeed, the ark had been stored in temporary circumstances for too long, since having been displaced from Shiloh. David had already shown the political foresight to establish his capital in Jerusalem and had every reason to turn his attention to building a new spiritual center for the kingdom. Ancient palaces of kings were often combined with adjoining temples. As we know, despite David’s heart and much of his wealth being dedicated to the vision of a temple, he wouldn’t live to see it built.

But even the brief points here in Deuteronomy lay out the primary impetus that spurred him and his son, Shlomo, to build the “House of the Lord.” While we’re inclined to view the temple primarily as a place for blood sacrifices, its true purpose is quite different and laid out clearly in 12:11: “the place Adonai your God chooses to have his name live.”

This temple is, above all, a place where God’s people will encounter the divine presence. We see that purpose substantially in evidence during the dedication of Shlomo’s Temple: a “cloud,” which once signified the Presence of the Lord that led Israel by day through the desert, reappears with new significance:

When the cohanim came out of the Holy Place, the cloud filled the house of Adonai, so that, because of the cloud, the cohanim could not stand up to perform their service; for the glory of Adonai filled the house of Adonai. (1 Kings 8:10–11)

As the psalmists often confirm, it is the Lord’s presence that draws Israel to worship at the Temple:

Go up, Adonai, to your resting-place,

you and the ark through which you give strength.

May your cohanim be clothed with righteousness;

may those loyal to you shout for joy. (Psa 132:8–9)

The presence of the Temple in the place “he chooses” (the point in Deuteronomy 12:11 is repeated emphatically in vv. 13 and 14) acts as a further sign confirming God’s unique covenantal relationship to the whole nation of Israel and the election of his people, whom he has brought up from bondage. This role of the Temple is explicitly envisioned in the Torah even earlier than Deuteronomy. At the very moment when the people celebrate their escape from the hand of Pharaoh and his army, the Song of Moshe declares:

You will bring them in and plant them

on the mountain which is your heritage,

the place, Adonai, that you made your abode,

the sanctuary, Adonai, which your hands established. (Exod 15:17)

Israel will experience the Temple as a source of blessing for the nation (Hag 2:15ff.) and yet it’s also to be a source of spiritual hope for the foreigner (who also receives attention in this parasha, since we were once foreigners in Egypt—see Deut 10: 19). Thus, in his prayer of dedication, Shlomo declared that the Temple would be a place for the nations to turn to when they seek the Lord (1 Kings 8:41–43), a vision further foreseen in Isaiah’s prophecy of a future when the Temple will be “a house of prayer for all peoples” (Isa 56:7).

Finally, of course, it is a place for sacrifice, for personal consecration, and to draw in the nation for the pilgrimage holy days in the spring and fall: “your burnt offerings, sacrifices, tenths, the offering from your hand, and all your best possessions that you dedicate to Adonai; and you will rejoice in the presence of Adonai” (Deut 12:12a). Nor is the Temple to be restricted to the elite, the wealthy, or the mature. Worshipers are commanded to include “your sons and daughters, your male and female slaves and the Levi staying with you, inasmuch as he has no share or inheritance with you” (Deut 12:12b).

All these visions that were fulfilled on a site where Israel worshiped for a thousand years now seem to lie shattered under the massive stone remains of Herod’s Temple. Many of us have walked among these ruins not far from the Western Wall, under the Al Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock. These tactile reminders of Yeshua’s prophetic warning, “not one stone will be left standing” (Matt 24:2; Mark 13:2; Luke 21:6) have often been seen in Christianity and Islam as a rebuke to Israel, the end of her covenant relationship with God.

But the restoration of Jerusalem as a Jewish city in 1967, also foretold by Yeshua (Luke 21:24), requires equal attention. The reclaiming of the Old City and the Kotel, Israel’s holiest site for worship, had international repercussions—the so-called “Jerusalem effect” which not only empowered Jewish identity for a generation, but has been directly linked to the rebirth of modern Messianic Judaism.

After spending precious time in prayer at the Kotel, I can attest, perhaps like many of you, to having experienced a profound sense of God’s presence. And I can’t help reliving the various sensations of my visits there: the humbling aura from those towering, massive stone walls that seem to embrace our prayers captured in the tiny notes crammed between the stones; the endless variety of visitors from around the globe; the prodding recollection that we have a generational duty to rebuild the Beit HaMikdash; the ascending flocks of swallows nesting in those ancient walls, a reminder that we are only a brief moment among all the generations since the original vision laid before Israel on the plains of Mo’av. And yet that kernel of a vision for “the place Adonai your God chooses to have his name live” is still shaping Jewish history, my history and yours.

All Scripture citations are from the Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

On the Border of the Promised Land

Our entire parashah illustrates a valid point for us today: unless we remember the past, our present has no foundation. As our people have put it often, ma’aseh avot, siman l’banim, “what happened to our ancestors in the past is a lesson for us, their descendants.”

Parashat Ekev, Deuteronomy 7:12–11:25

David Friedman, UMJC Rabbi, Jerusalem

As our parashah begins, our ancestors are standing on the border of the Land of Promise, readying themselves to enter by listening to Moshe’s teachings for a month-long time period. Our entire parashah illustrates a valid point for us today: unless we remember the past, our present has no foundation. As our people have put it often, ma’aseh avot, siman l’banim, “what happened to our ancestors in the past is a lesson for us, their descendants.”

The coming entry into Israel for our ancestors must have been an exciting time. Their nomadic existence was about to change, as they would now eat normal food, drink water from springs and rivers in the Land, experience cooler weather, live in their own private homes on their own private land holdings, and be able to pursue their own affairs. To live properly, according to the Torah, would be the center-point of this new national life. This alone would determine whether the tribes would be blessed by God in their new home. So we find Moshe busy, driving home lessons for the people to remember as they embark on their new life together.

Moshe emphasized something crucial in his tamsit (the overall main point of our parashah’s teaching). We find it in Deuteronomy 10:12–13:

And now, O Israel, what does Adonai your God, ask of you? Only to fear Adonai your God, to walk in all His ways and to love Him, and to worship Adonai your God, with all your heart and with all your life, and to keep the instructions of Adonai, and His statutes, which I teach you this day, for your good. (Chabad translation, modified)

Everything that Moshe instructs the people in today’s parashah centers around these two verses. Fearing God, loving him, keeping his instructions and worshiping him is what Moshe is encouraging them to do. Indeed, the things mentioned in these two verses are all-encompassing. All of life was to be brought under the protective and holy wings of God. Similar to Deuteronomy 6:4–6, which we read in last week’s parasha, these verses are telling us that every aspect of life is to be lived for God’s purposes. This is not a complicated message. It’s not secretive, it's not reserved for only kohens, Levites and tribal elders. It is what is required of everyone in the nation, from all 12 tribes.

What would be the consequences if the nation did what vv. 12–13 state? What would happen if the entire nation followed and obeyed God? Once again today’s parashah answers this question:

And it will be, because you will heed these ordinances and keep them and perform, that Adonai your God, will keep for you the covenant and the kindness that He swore to your forefathers. And He will love you and bless you and multiply you; He will bless the fruit of your womb and the fruit of your soil, your grain, your wine, and your oil, the offspring of your cattle and the choice of your flocks, in the land which He swore to your forefathers to give you. You shall be blessed above all peoples: There will be no sterile male or barren female among you or among your livestock. And Adonai will remove from you all illness, and all of the evil diseases of Egypt which you knew, He will not set upon you, but He will lay them upon all your enemies. (7:12–15, Chabad translation)

In these verses we see God’s intentions—that the people would be blessed richly through their obedience and Torah-loving lifestyle. But as always, Torah is honest and gives us both sides of the story. What would be the consequences if the nation didn’t follow and obey God? (The book of Judges details what this looked like in real history.) Our parashah tells us what ignoring God’s instructions will result in:

If you forget the Lord your God and follow other gods, and worship them, and prostrate yourself before them, I bear witness against you this day, that you will surely perish. (Deut 8:19)

And again:

Beware, lest your heart be misled, and you turn away and worship strange gods and prostrate yourselves before them. And the wrath of Adonai will be kindled against you, and He will close off the heavens, and there will be no rain, and the ground will not give its produce, and you will perish quickly from upon the good land that Adonai gives you. (Deut 11:16–17)

In a common ancient Torah discussion (termed pilpul, literally a “peppering” of questions and answers), our holy Messiah was asked: “Rabbi, which is the greatest mitzvah (instruction) in the Torah?” The questioner was asking Yeshua, “Rabbi, would you boil the Torah down to what we have to do to please God?” It’s not a bad question; in fact it’s a good one, one that lots of rabbis were asked and responded to throughout Jewish history, up until today. Our holy Messiah Yeshua responded: “‘Love Adonai your God with all your heart and with all your life, and with all your wealth.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Torah and the Prophets hang on these two instructions.” (Matt 22:37–40 NIV, modified)

At the very end of our parashah, the previous instructions of Deuteronomy 6 are repeated. They explain to us that the Torah must always be set before us, as our blueprint, our guide, and must always encompass our ideals as a people:

And you shall set these words of Mine upon your heart and upon your life, and bind them for a sign upon your hand and they shall be for ornaments between your eyes. And you shall teach them to your sons to speak with them, when you sit in your house and when you walk on the way and when you lie down and when you rise. (11:18–19, Chabad translation)

So today’s parashah is Moshe’s tamsit for Israel, that is, his focus on a main and crucial point that he continually emphasizes throughout all of his teachings in the Torah. He strategically teaches it in today’s parashah, right before the entry into the Land of Israel. That time was a very historic and important set of days in which to review how to live in order to receive God’s blessings in the Land. And that is what we see him doing: teaching vigorously so that the people will take what is important to them into the Land, and remember . . . to love Adonai at all times. We should pay attention to this crucial teaching today, so that its truth will not be lost upon us, the banim (descendants) of ancient Israel. As it is written: ma’aseh avot, siman l’banim—what happened to our ancestors is a lesson for us.

Shabbat shalom!

Torah Tips for a Tough Text

I’ve been dialoguing with a Jewish friend of mine who is reading through the Torah and asking me questions. Recently, he asked me something I’ve heard other folks ask as well, “What does it mean that the Jewish people are chosen? Isn’t that kind of self-centered?”

Parashat Va’etchanan, Deuteronomy 3:23-7:11

David Wein, Tikvat Israel Messianic Synagogue, Richmond, VA

I’ve been dialoguing with a Jewish friend of mine who is reading through the Torah and asking me questions. Recently, he asked me something I’ve heard other folks ask as well, “What does it mean that the Jewish people are chosen? Isn’t that kind of self-centered?” In response, I thought of Sha’ul’s encouragement to the community in Corinth:

For you see your calling, brothers and sisters, that not many are wise according to human standards, not many are powerful, and not many are born well. Yet God chose the foolish things of the world so He might put to shame the wise; and God chose the weak things of the world so He might put to shame the strong; and God chose the lowly and despised things of the world, the things that are as nothing, so He might bring to nothing the things that are—so that no human might boast before God. (1 Cor. 1:26-29, TLV)

Paul is suggesting that chosenness is a matter of God’s favor on the “weak” who are strong in Hashem. But I wanted to give my friend an equivalent encouragement from the Hebrew Scriptures, so I suggested he read Deuteronomy 7, which is in this week’s parashah:

It is not because you are more numerous than all the peoples that Adonai set His love on you and chose you—for you are the least of all peoples. Rather, because of His love for you and His keeping the oath He swore to your fathers, Adonai brought you out with a mighty hand and redeemed you from the house of slavery, from the hand of Pharaoh king of Egypt. (Deut 7:7-8)

“Same idea,” I thought. “This will be encouraging,” I thought. Israel was chosen not because they were great and mighty but because they were weak and through them God’s redemption would unfold. However, I forgot about the verses right before this passage:

When Adonai your God brings you into the land you are entering to possess and drives out many nations before you—the Hittite and the Girgashite and the Amorite, the Canaanite and the Perizzite, the Hivite and the Jebusite, seven nations more numerous and mightier than you—and Adonai your God gives them over to you and you strike them down, then you are to utterly destroy them. You are to make no covenant with them and show no mercy to them. You are not to intermarry with them—you are not to give your daughter to his son, or take his daughter for your son. For he will turn your son away from following Me to serve other gods. Then the anger of Adonai will be kindled against you, and He will swiftly destroy you. Instead, you are to deal with them like this: tear down their altars, smash their pillars, cut down their Asherah poles, and burn their carved images with fire. For you are a holy people to Adonai your God—from all the peoples on the face of the earth, Adonai your God has chosen you to be His treasured people.

My friend came back to me, after my recommendation:

“I read Deuteronomy 7.”

“So, what’d you think?” I inquired.

“You know, it’s this sort of thing that turned me off from Judaism and the Torah many years ago.” (It was here that I remembered the bit in this chapter about utterly destroying those seven nations.)

“Ah, yes,” I stammered.

“Why does God say to destroy these other people in the land?”

“Well, I can offer some explanation now, but let me do some research and get back to you on that.”

So, as an open letter to my friend, here is the result of that research, starting with seven interpretive Torah tips for tough texts:

Look to the immediate context

Look to the halakhah

Look to the morality in Torah

Look to the ancient near east worldview

Look to the Shema

Look to the messianic era

Look to Yeshua

First, let’s look to the immediate context. Notice in the original text, that it has already begun to be interpreted. The interpretation of the “destruction” (kherem in Hebrew) comes as “don’t intermarry with them” and “get rid of their high places and idols.” In other words, it’s a caution against idolatry. Intermarriage seems to function well in the Scriptures (as with Ruth) when the non-Israelite spouse clings to the God of Israel, and the people of Israel. Otherwise, as with King Solomon, it can lead to idolatry.

This brings us to halakhah, which is tip number two. First, how is this interpreted later in the Scriptures themselves? The theologian Matthew Lynch provides this example:

In the book of Kings, we read how the High Priest Hilkiah found the long lost ‘Book of the Law’ in the Temple, which most think is the book of Deuteronomy. When Josiah heard the book read, he was horrified that he and the people were not in compliance.

So, Josiah went on a rampage, tearing down every known place of illicit worship. The narrator of Kings makes a point of the fact that Josiah carried out all the commands of Deuteronomy 7:5 (the kherem text), but not against Canaanite peoples. Instead, he carried out kherem against (Israelite!) places of worship.

In other words, Josiah carried out the kherem command of Deuteronomy 7:5, yet without exterminating entire people groups. He didn’t go hunting for Hivites and Girgashites, but instead, understood the true sense of the law by seeking radical differentiation from all forms of “Canaanite” religion.

Later halakhah within Judaism follows the logic of the righteous king, Josiah: worshiping the God of Israel alone.

This brings us to tip number three: look to the morality in Torah. The general thrust of the ethic in Torah is very clear on this matter: be kind to the stranger, because you were strangers in Egypt. The laws and counsel about compassion for the ger (resident immigrant) abound, and were probably used as the backbone for Paul’s counsel and encouragement towards non-Jews in the body of Messiah. These are part of the immutable laws (covenant) that is binding on Israel for all time, always. The kherem instructions are always bound by a specific circumstance; not so with the covenantal laws.

Would that I could elaborate on tips four through seven, but this drash has a word limit, so I suppose for the rest of the story, you’ll have to listen to my sermon this week in person, via zoom, or later on the Tikvat Israel podcast (available wherever fine podcasts are downloaded). Shameless plug notwithstanding, I will close with a bit of tip number seven. Some words from Yeshua, the living Torah, on how we should treat our enemies:

You have heard that it was said, “You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.” But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes His sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. (Matthew 5:43-45)

Tisha B'Av: Facing Our Traumas

For the Jewish people, summer brings the anniversary of our greatest national trauma. On Tisha B’Av, we don't simply mourn the loss of a building—we grieve the pain of divine abandonment. As Lamentations (the megillah or scroll customarily read on Tisha B'Av) asks: “Eicha?” or “How?—how could all this happen?”

Tisha B’Av 5781

by Yahnatan Lasko, Beth Messiah Congregation, Montgomery Village, MD

“Tell me about the most traumatic thing that ever happened to you.”

I was seated on the couch. Across from me sat a counselor. His question surprised me not with how personal it was, but because of how quickly its answer would usher him into the heart of my personal pain, fears, and struggles.

Some of us have been blessed with relatively trauma-free lives. But others have experienced a trauma in our past. It may have been a betrayal by a loved one, or perhaps a tragic accident. In the midst of these painful circumstances, we may even question God: “How could you let this happen?”

For the Jewish people, summer brings the anniversary of our greatest national trauma. On Tisha B’Av, we don't simply mourn the loss of a building—we grieve the pain of divine abandonment. As Lamentations (the megillah customarily read on Tisha B'Av) asks: “Eicha?” or “How?—how could all this happen?”

Like the garden He laid waste His dwelling,

destroyed His appointed meeting place.

Adonai has caused moed and Shabbat

to be forgotten in Zion.

In the indignation of His anger

He spurned king and kohen.

The Lord rejected His altar,

despised His Sanctuary.

He has delivered the walls of her citadels

into the hand of the enemy.

They raised a shout in the house of Adonai

as if it were the day of a moed. (Lam 2:6–7)

The author's pain is palpable:

How can I admonish you?

To what can I compare you,

O daughter of Jerusalem?

To what can I liken you, so that I might console you,

O virgin daughter of Zion?

For your wound is as deep as the sea!

Who can heal you? (Lam 2:13)

The poem of the ensuing chapter contains a confession of Israel’s own liability for the Temple’s destruction: "We have sinned and rebelled, and you have not forgiven” (Lam 3:42). The sages of the Talmud similarly acknowledged Israel’s role in bringing about the destruction of the Second Temple:

But why was the second Sanctuary destroyed, seeing that in its time they were occupying themselves with Torah, mitzvot, and gemilut chasidim [the practice of charity]? It fell because of sinat chinam [hatred without cause]. (Yoma 9b)

Given all this pain and loss, sin and judgment, is it surprising that we find Messiah at the center? Forty years before the destruction of that Second Temple, Yeshua came into Jerusalem and pronounced words of judgment over the city and its temple. These pronouncements came from Messiah not in triumph, but rather in a deep lament:

O Jerusalem, Jerusalem who kills the prophets and stones those sent to her! How often I longed to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing! Look, your house is left to you desolate! (Matt 23: 37–38)

Just a few days later, Yeshua himself experienced divine abandonment in the most profound sense. Hanging on a cross, he uttered his last words, according to Matthew’s and Mark’s accounts: “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?”—”My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (Matt 27:46, Mark 15:34). With his last cry, Yeshua prophetically binds himself to the impending divine judgment he himself prophesied, going ahead of the Jewish people into exile.

What is your greatest trauma? Have you struggled at times, asking God, “Where were you when this happened to me?” Perhaps you try to minimize the pain by avoiding the memory altogether, yet still it haunts you, rushing in at unexpected times.

We can try to numb ourselves, but ignoring traumas won’t make them go away. Difficult as it may be, only facing our traumas enables us to truly hear words of comfort such as those of Isaiah 53:4: “Surely he . . . carried our sorrows.”

Facing trauma is just as necessary corporately as it is individually. As the apostle Paul wrote to the Yeshua-believing community in Corinth, “Godly sorrow brings repentance, which leads to salvation” (2 Cor 7:10 NIV). By entering into the trans-generational sorrow of our people on Tisha B’Av, we not only position ourselves to truly hear God’s words of comfort, but we also help to sustain the tradition of godly sorrow, hastening the day when all Israel will receive Messiah and his Spirit of comfort. If you are a gentile, you are not only enjoined to mourn together with Israel (Rom 12:15b); you are also uniquely able to fulfill key elements of Israel's consolation as written in the Prophets (Isa 60:1–16; 61:5, 9).

So as we approach Tisha B’Av this year, let these words of Yeshua guide us: “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.”

This article first appeared in the Summer 2010 UMJC Twenties Newsletter. All Scripture references, unless otherwise noted, are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

How to Rebuke with Respect

If you love someone, honor them, even at your own expense. Get in the habit of safeguarding others’ honor and reputation. The starting point for this is being in touch with your own infinite value; only one who is secure in their place, who has “reputation to give,” as it were, is able to guard others’ honor generously.

Parashat Devarim, Deuteronomy 1:1–3:22

David Nichol, Congregation Ruach Israel, Boston

One of my favorite aspects of the Jewish interpretive tradition is the mileage the sages get out of the text of Tanakh. I recently heard Rabbi Ethan Tucker compare the way the rabbis of the midrash read the Torah to how one might read a love letter. A lover who receives a letter from their beloved will find meaning in the placement of a comma or an unusual word choice. If we read the Torah as a letter from God, the more lovesick we are, the more we read meaning into every pregnant pause, unconventional spelling, and unexpected phrasing. The rabbis of the midrash exemplify this approach, seeming to say, if we yearn deeply to hear the voice of God, we take even little details of the text very seriously; we read not just between the lines, but between every letter.

So it’s no surprise that the midrash finds something of note in the very first verse of Parashat Devarim:

These are the words that Moses spoke to all Israel across the Jordan—in the wilderness, in the Arabah opposite Suph, between Paran and Tophel, Laban, Hazeroth and Di-Zahab. (Deut 1:1)

It begins, “V’eleh hadevarim asher diber Moshe el kol Yisra’el,” “These are the words which Moses addressed to all Israel...” Immediately we might ask, why does it not just start with vayomer Moshe, “Moses said…,” or vaydaber el kol Yisra’el, “Moses spoke to all Israel”? Why does it start with, “These are the words”?

Of course, the sages asked the same question. Rashi, following the midrash (Sifrei Devarim) and targums (ancient Aramaic translations of Tanakh), reads “words” here as “words of rebuke.” After all, the midrash reasons, look at other uses of davar/devarim (“word/words”) in Tanakh. Many of those usages precede a rebuke or admonition, such as Amos 1 (“The words of Amos…”), Jeremiah 7 (“The word which came to Jeremiah...”), and others.

So if the (seemingly extraneous) use of devarim/words in the passage indicates rebuke, where is this rebuke? Read in full, Rashi’s comment explains:

Because these are words of reproof and he is enumerating here all the places where they provoked God to anger, therefore he suppresses all mention of the matters in which they sinned and refers to them only by a mere allusion contained in the names of these places out of regard for Israel [or “for the honor of Israel”].

It is the place names themselves that include the rebuke. Where Moses seems to be just listing a bunch of place names, he’s in fact alluding to the events that happened there. It’s like when I remind my wife about the late-night stop at the service area near Rochester, NY, on a car trip to Michigan. I don’t need to add, “You know, when both kids were vomiting in their car seats.” Believe me, she remembers. So the Israelites presumably cringe at the mention of these places.

This raises the question: why not be more explicit? Everybody knows what happened! Why does the text not just spell it out? Why not just say it? The first verse could have been like this:

These are the words which Moses spoke with all Israel beyond the Jordan, reproving them because they had sinned in the wilderness, and had provoked the Lord to anger on the plains over against the Sea of Suph, in Pharan, where they scorned the manna; and in Hazeroth, where they provoked to anger on account of flesh, and because they had made the golden calf.

In fact, that’s exactly how it’s rendered by the ancient Aramaic translation, Targum Onkelos (~4th century CE). However, the text of the Torah is much more subtle, not mentioning these specific events at all.

I propose two reasons that Moses might be circumspect with respect to Israel’s sins in the wilderness. First, the dignity of humans is a central Jewish value; conversely, public humiliation is a serious offense. The Talmud underscores the seriousness by stating that “anyone who humiliates another in public, it is as though he were spilling blood” (Bava Metzia 58b). Quoted above, Rashi attributes the circumspection to God’s concern for Israel’s honor or glory.

This leads us to ask why God is so concerned about Israel’s honor. Certainly human dignity is important; according to the Talmud, guarding the dignity of another takes precedence even over the observance of a prohibition in Torah (Berakhot 19b). But even more fundamentally, God loves Israel, and we care about the honor of those we love. “When Israel was a youth I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son” (Hos 11:1).

The second reason is more practical. This speech from Moses isn’t about dwelling on the past. The sins of Israel aren’t decisive enough to fracture the relationship. No, Israel has a mission, a shelichut, something to accomplish. Just a few verses later, God tells the people that it’s time to get moving: “You have stayed long enough at this mountain. Turn, journey on…” (1:6). It’s been forty years, and it’s not the time for rehashing old arguments, or bringing up failures of the past. That would be a distraction from the task at hand.

We can learn lessons from both of these reasons.

If you love someone, honor them, even at your own expense. Get in the habit of safeguarding others’ honor and reputation. The starting point for this is being in touch with your own infinite value; only one who is secure in their place, who has “reputation to give,” as it were, is able to guard others’ honor generously. Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe put it well:

The beginning of all individual work is specifically the experience of man’s exaltedness. Anyone who has never focused on man’s exaltedness from his very creation, and whose only self-work is to know more and more about the bad sides of himself and to make himself suffer as a result—that person will sink deeper and deeper into despair, and in the end, will make peace with the bad out of sheer lack of hope of ever changing it. (Alei Shur, vol 1)

But our insecurities are in vain, since our value is beyond measure! As Yeshua said, “Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them shall fall to the ground apart from your Father’s consent. But even the hairs of your head are all numbered. So do not fear; you are worth more than many sparrows” (Matthew 10:30-31).

Once you are confident in your own value, you become free to turn toward reminding those you love of their intrinsic worth.

And who hasn’t rehashed old arguments, allowing themselves to focus on their own anger or unresolved feelings of betrayal, processing their own anger in the guise of rebuking another? There is always a temptation to reach into the bag and bring out old offenses, recycling the weapons that once hurt you, to hurl them back at their original owner. But to do so is rarely helpful.

I find this to be particularly relevant as a parent. Certainly some of the “rebukes” directed toward my children are for the sake of their edification and growth. But all of them? Hardly. Sometimes it’s more about me than about what is best for them.

On the other hand Moses seems to anticipate Paul’s words: “Let no harmful word come out of your mouth, but only what is beneficial for building others up according to the need, so that it gives grace to those who hear it” (Eph 4:29).

And so in one verse, we find deep teachings about how to relate to each other by imitating the Creator. May he strengthen our hands to preserve each other’s honor, and when we must rebuke, to do so in proper measure, and out of love.

Individualism Meets Responsibility

The concept of individualism tempered by participation in the collective whole has been challenged this past year, as the emphasis on individuals and their rights seems to have skyrocketed. The problem is that individualism apart from participation in the collective whole leads to chaos.

Parashat Matot-Masei, Numbers 30:2–36:13

Dr. Vered Hillel, Netanya, Israel

Right action tends to be defined in terms of general individual rights and standards that have been critically examined and agreed upon by the whole society. —Lawrence Kohlberg, American psychologist known for his theory on the stages of moral development

The concept of individualism tempered by participation in the collective whole has been challenged this past year, as the emphasis on individuals and their rights seems to have skyrocketed. The problem is that individualism apart from participation in the collective whole leads to chaos. For example, see the closing verse of the book of Judges (21:25): “In those days there was no king in Israel. Everyone did what was right in his own eyes.” But when individual uniqueness and rights are tempered in relationship to the collective whole, orderliness and harmony abound.

This week’s Torah portion exemplifies Kohlberg’s statement, as it demonstrates the intertwining of the rights, actions, and situations of individuals with the needs of the collective whole. Our parasha concludes the Book of Numbers, which records the final segments of Israel’s journey from Egypt to the land of Canaan. It ends with the children of Israel standing on the banks of the Jordan River in Moab, ready to cross into the Promised Land. The forty-two places Israel encamped during their forty-year period of wandering in the wilderness are recorded in Numbers 33:1–49. This itinerary points out that the Jewish people were on a real, historical, flesh-and-blood journey and also reveals things about B’nei Israel’s spiritual journey, about their relationship with Adonai and the calling they would embody once in the Promised Land. Hashem planned and directed Israel’s every move. He declared his mercies and compassion, as well as his great love for his chosen people, throughout the adventure. During the journey, Hashem taught Israel to love and fear him and to trust and appreciate the security, love, and care he provides. The itinerary demonstrates Hashem’s love and care for the community as a whole.

In last week’s parasha, Pinchas, we saw Hashem’s love, care, and justice for individuals through the story of Zelophehad’s daughters (Num 27:1–7). This week’s parasha picks up the saga of Zelophehad’s daughters in the final verses of both the parasha and the Book of Numbers (36:1–13). When read together, the two parts of the daughters’ story illustrate the importance of individuals being an active part of a collective whole, meaning a tribe, people-group, or society.

In part one, Zelophehad’s daughters approached Moses and the leaders of the children of Israel requesting the right to inherit their deceased father’s land allotment, since there were no sons (Num 27:1–7). The sisters requested their rights as individuals, not as a group. They were individuals who needed to be treated according to their uniqueness and particularities, including their extraordinary situation; no previously-given legislation or precedent existed upon which to base a decision. So Moses, as was his pattern, took the matter to Hashem, who recognized the justice of the sisters’ cause and granted their request. This incident demonstrates the importance of Hashem’s love and care for individuals and that each person’s unique identity, rights, and situations are particular to them.

Part two of the story tempers the rights of the individual with that of the collective whole. The leaders of Zelophehad’s clan approached Moses and the leaders of the children of Israel, just as the daughters had done. The clan leadership objected to the daughter’s inheritance of their father’s land. The leaders rightly claimed that if the daughters were to marry outside of the tribe of Manasseh, the land would automatically pass to the husband’s tribe, thereby depriving the tribe of Manasseh of its land inheritance. Here again there was no legislation or precedent upon which to judge the request. Moses took the request to Hashem, who recognized the justice of the leaders’ request. As a result, Moses decreed that Zelophehad’s daughters must marry within the tribe of Manasseh, which is exactly what the young women did; they married their first cousins, their father’s nephews. The complete story of Zelophehad’s daughters, part 1 and part 2, teaches us the importance of balancing our individual uniqueness, situations, and rights with the larger collective whole.

The importance of balancing individual uniqueness and rights with the good of the collective whole is also seen in the request by Reuben and Gad to settle in the conquered territory on the east-side of the Jordan River (Num 32:1–38). Initially Moses emphatically rejected their request, but after subsequent discussion a compromise was reached. Moses conceded to the request of the two tribes with the stipulation that they would cross the Jordan River and battle alongside the children of Israel until every tribe was settled in the land of inheritance. The tribes of Gad and Reuben initially spoke from their individuality as a tribe, without regard for B’nei Israel as a whole. They were looking out for themselves; their highest priority was their wealth and prosperity, and their own comfort and future. These two tribes only consented to help all of the children of Israel settle in the land after their negotiations with Moses and their acceptance of his stipulations. The tribes of Gad and Reuben received their individual requests, in essence establishing their individual rights. At the same time, these individual requests were tempered by the demand for the two tribes to fight alongside all of Israel until the entire community was settled in the land of Canaan. Three clans from the tribe of Manasseh also settled on the east side of the Jordan River. However, they never requested this privilege, nor were they given any stipulations as were the tribes of Gad and Reuven. First, it seems that the land allotted to the tribe of Manasseh on the east side of the Jordan falls within the territorial boundaries of the children of Israel as outlined in Numbers chapter 34, so it was already designated as part of their inheritance. Second, the other half of the tribe of Manasseh settled in the Land of Canaan, choosing to join the collective whole of Israel, whereas Gad and Reuben did not.

We are currently in the three weeks of repentance before Tisha B’Av. Let us use this time to reflect on how our individual uniqueness can be tempered in light of our participation in the People of God, our communities, society, and countries. Remember Peter’s exhortation, “you like living stones are being built together into a spiritual house” (1 Pet 2:5).

Chazak, chazak, v’nitchazek! Be strong, be strong, and let us be strengthened!

Illustration from https://www.fruitfullyliving.com/.

Jerusalem the Waiting Bride

The words of Jeremiah the prophet draw our attention beyond our undeniable failures as a people to our equally undeniable foundation as a people chosen and loved by God. And it’s particularly striking that the Lord is speaking here specifically to Jerusalem.

The First Haftarah of Affliction, Jeremiah 1:1–2:3

Rabbi Russ Resnik

The words of Jeremiah, the son of Hilkiah . . . to whom the word of the Lord came in the days of Josiah the son of Amon, king of Judah . . . until the end of the eleventh year of Zedekiah, the son of Josiah, king of Judah, until the captivity of Jerusalem in the fifth month. (Jeremiah 1:1–3)

The fifth month of the Hebrew calendar is Av, and on its ninth day, Tisha b’Av, 586 BCE, the holy temple was destroyed by the Chaldeans, launching what Jeremiah describes starkly as “the captivity of Jerusalem.” For three weeks leading up to this mournful day, we read passages from the prophets, the Haftarot of Affliction, beginning with Jeremiah chapter 1.

Jeremiah describes his calling from God, who set him apart from before birth as a prophet to bring a message warning of judgment to come, along with a hint of hope:

Behold, I have put my words in your mouth.

See, I have set you this day over nations and over kingdoms,

to pluck up and to break down,

to destroy and to overthrow,

to build and to plant. (Jer 1:9b–10)

Jewish tradition doesn’t ignore the warnings of judgment, and we recognize the past judgment on Tisha b’Av each year, but our tradition teaches us to also look for the note of hope—“to build and to plant.” And so the reading for this week concludes with the first three verses of Jeremiah 2:

The word of the Lord came to me, saying, “Go and proclaim in the hearing of Jerusalem, Thus says the Lord,

“I remember the devotion of your youth,

your love as a bride,

how you followed me in the wilderness,

in a land not sown.

Israel was holy to the Lord,

the firstfruits of his harvest.”

This lovely vision pictures Hashem’s romance with Israel, who followed him out of Egypt and into the wilderness like a bride devoted to her husband. The prophet’s words draw our attention beyond our undeniable failures as a people to our equally undeniable foundation as a people chosen and loved by God. And it’s particularly striking that Hashem is speaking here specifically to Jerusalem. Jerusalem didn’t literally follow him in the wilderness and had no apparent role in the narrative of redemption from Egypt at all. Yet, by Jeremiah’s time, Jerusalem represents the soul of the people Israel, so that her story and Israel’s story are deeply intertwined.

. . .

In the days of his earthly ministry, Messiah Yeshua looked ahead to another Tisha b’Av—the date of a second destruction of the temple, this time by Rome, in 70 CE. On his way to Jerusalem for his final Passover, Yeshua is well aware of his coming crucifixion, and yet even more troubled by the crucifixion of Jerusalem that will come not long afterwards. Some Pharisees have warned him that Herod, ruler of Galilee, is seeking to kill him, so he’d better move on, and Yeshua replies,

Go and tell that fox . . . “It cannot be that a prophet should perish away from Jerusalem.” O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing! Behold, your house is forsaken. And I tell you, you will not see me until you say, “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!” (Luke 13:32–35)

The last two verses here (13:34–35) appear also in Matthew 23:37–39, but in a different context. In Matthew, Yeshua says these words not on the way to Jerusalem, as in Luke, but after his triumphal entry into the city when the crowds had called out, “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!” (Matt 21:9). In Matthew’s version, therefore, the promise “you will not see me” contains an additional word—“again” (Matt 23:39). This minor detail suggests that Matthew sees the triumphal entry as a prophetic enactment of Yeshua’s future return, when Jerusalem will see him “again” and this time cry out “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!”

There’s another difference in the two accounts. In Matthew 23:37, Yeshua says to Jerusalem “you were not willing” after having a number of disputes with the Jerusalem authorities (Matt 21:10–22:46). In Luke’s version, however, Yeshua says “you will not see me” before he has even arrived in Jerusalem, and before he has tested Jerusalem’s “willingness” to respond.

How then do we interpret Yeshua’s sadness at Jerusalem’s rebuff, apparently before it even happens? How can Yeshua claim that the city “will not see” him, shortly before he shows up and is seen there? Yeshua seems to be acting here as a prophet speaking God’s own words in the name of God. As commentator Robert Tannehill argues, the words “how often have I desired to gather you” (Luke 13:34) refer to “the long history of God’s dealing with Jerusalem,” and the words “you will not see me” likewise refer not to Yeshua, but to God: “Verse 35 is speaking of the departure of Jerusalem’s divine protector, who will not return to Jerusalem until it is willing to welcome its Messiah, ‘the one who comes in the name of the Lord.’”

This interpretation brings Luke 13 into harmony with our first Haftarah of Affliction, Jeremiah 1:1–2:3. In Luke’s account, the longing for Jerusalem’s welcoming response belongs not only to Yeshua but even more to God, whose love for the city and whose grief at its wickedness is not a recent development but has extended through multiple generations, as Jeremiah also reveals. Accordingly, the predominant tone of Yeshua’s words here is one of lament. Nevertheless, a more positive note emerges in the end: “You will not see me until you say, ‘Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!’” (Luke 13:35, emphasis added). We have reason to hope that the divine presence, whose departure renders the city vulnerable to its enemies (“Behold, your house is forsaken”), will return again, to comfort and glorify Jerusalem.

The condition for such a future return is clear: the city—apparently still in its character as the capital of the Jewish people—must offer the same welcome to the Messiah that he will receive from his Galilean followers later in Luke’s account, when he enters the city a few days before Passover.

Yeshua’s crucifixion during Passover sets the stage for his resurrection on the third day. It also expresses Yeshua’s identification with Jerusalem, which will endure a similar fate at the hands of Rome a generation later—and will be resurrected when Messiah returns. Crucifixion bears the seed of resurrection to come. Tisha b’Av is a day of mournful remembrance, but also a day of hope.

But let’s seek not only hope for the future but also guidance for life today in the words of Jeremiah and Messiah Yeshua, in the way they both speak of Jerusalem. Hashem chooses to address his people not in abstract or generic terms, but in intimate terms as Jerusalem his bride. Yeshua verbalizes God’s intimate longing to gather Jerusalem’s children under his wings. They both remind us to pay attention to the living, breathing, impassioned person near us, to not turn persons into objects, either of our admiration or, perhaps more commonly, of our disdain. God looks at a face and remembers a story even as he warns of judgment to come. We can do something similar amid our everyday encounters, as we treat others with kindness and dignity. Thus we can have hope not only for the future redemption, sure to come, but also for redemptive human interaction while we await it.

Portions of this drash are adapted from Besorah: The Resurrection of Jerusalem and the Healing of a Fractured Gospel, by Mark Kinzer and Russ Resnik. Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2021.

Scripture references are from the ESV.

Almost a Prophet

Like a play within a play, the episode with Balaam confronts us with a truly paradoxical figure: a God-fearer who could prophetically proclaim the rise of Israel but dies merely a soothsayer, almost as a passing footnote.

Parashat Balak, Numbers 22:2–25:9

Ben Volman, Kehillat Eytz Chaim, Toronto

Like a play within a play, the episode with Balaam (or as in the CJB, Bilam) confronts us with a truly paradoxical figure: a God-fearer who could prophetically proclaim the rise of Israel but dies merely a soothsayer, almost as a passing footnote. Strangely enough, the rabbis actually refer to this lengthy interlude as “the book of Balaam.” In his day, Balaam must have been of great repute. Yet in this sidra featuring his four great oracles, he’s portrayed with a mixture of honor and comic relief. Even with the long shadow cast by his prophecies, the rabbis generally give him short shrift.

It all begins with an offer from Balak, the Moabite king, that he was sure Balaam could not refuse: a lavish fortune to place curses on Israel. It was an era when armies had professional sorcerers to curse their enemies, but Balaam’s original answer suggests an unexpected spiritual depth from this gentile: “Even if Balak were to give me his palace filled with silver and gold, I cannot go beyond the word of Adonai my God to do anything, great or small” (22:18).

Though warned by God to only do what God has allowed (v. 20), an unsuspecting Balaam has incurred the Lord’s wrath. While urging his donkey toward the rendezvous with Balak, he’s riding into the drawn sword of the Angel of the Lord. The master may be blind, but the donkey isn’t. The beast, acting as the true “seer” is only the first of several humiliations.

Under Balaam’s repeated furious beating, the donkey that saved his life speaks up. Perhaps we can explain this not as the voice of the donkey, but more the ventriloquist work of the Lord. The irony is fully played out when the master angrily yells at his donkey he wishes he had a sword to kill it just as his eyes are opened to the death-wielding Angel.

Balaam seems truly chastened. And his relationship with the Lord appears genuine enough to earnestly speak the words ba’al peh, placed in his mouth. Rashi is not impressed, however, and thinks that the description of God making himself manifest to Balaam (va-yikar—literally “he fell in”) suggests a lesser relationship than God had with true prophets.

Still, the poetry is not just impressive, but resonates through history, as in, “a people that will dwell alone / and not think itself one of the nations” (23:9). This description of Israel as distinctively separate is now almost taken as doctrine in a common worldview divided between Jew and gentile. And there’s brilliant word-play: “May I die as the righteous die!” with “righteous” translated from y’sharim—echoing the name of Israel, Y’shurun (23:10).

When his original plan fails, Balak presses the seer to try another spot for cursing. Balaam can only proclaim: “Look, I am ordered to bless; / when he blesses, I can’t reverse it. / . . . Adonai their God is with them / and acclaimed as king among them” (23:20–21). As for the Israel that Balaam elaborately depicts with the strength and power of a lion and a lioness—we barely recognize that people, which has been struggling since they left Egypt, resisting God, arguing with Moshe, and complaining the full length of the desert. Now they’re praised as fully worthy of blessing: “How lovely are your tents, Ya‘akov; / your encampments, Isra’el!” (24:5).

Balak urges Balaam to stop, “Don’t curse and don’t bless.” Instead, Balaam will prophesy of Israel’s coming dominance: “They shall devour enemy nations” (24:8). Finally, there is a promise that will again resonate for centuries as a promise identified with Messiah, and applied by Rabbi Akiva in the second century CE to Bar Kochba: “I behold him, but not soon — / a star will step forth from Ya‘akov, / a scepter will arise from Isra’el” (24:17ff.).

An infuriated Balak tells the seer that he’s never getting that promised wealth, and instead receives Balaam’s prophecies of the “last days” against Israel’s enemies. When they part ways, the rabbis interpret the place to which Balaam returned (li’m’kmo, his place) to mean “hell” (Mishnah Par. 3:5).

But we will see him again. In Numbers 31 we learn that Balaam set a trap for the men of Israel, seducing them to the immoral worship and prostitutes that please the Ba’al gods of fertility. Except that Balaam’s cleverly covert ways have finally led to his ruin—and he is slain with Israel’s enemies at Midian.

That’s not the last word on him, by any means. He’ll be repudiated later in Deuteronomy, then Joshua, Nehemiah, Micah, and on into the B’rit Chadashah, including this condemnation by Peter (Kefa): “These people have left the straight way and wandered off to follow the way of Bil‘am Ben-B‘or, who loved the wages of doing harm but was rebuked for his sin” (2 Peter 2:15–16).

Was he a real prophet or a gifted soothsayer? The Talmud suggests that he began as a true prophet, but abandoned the faith for gain—so that the original oracles were authentic, but these were to him like a “fishhook” from which he struggled to break free (Sanh. 105a–106b).

Another surprise—his name is written into fragments of writing on a plastered wall in an ancient Temple in Deir’Alla, Jordan (about 70 kms north of the Dead Sea). This unique archaeological find recounts a strange vision of the notable seer clearly identified as “Bal’am son of Be’or.” Again we’re reminded, this man must have been a notable figure in his day.

“Absolute power corrupts absolutely,” but most of us are corrupted with much more gradual, incremental steps off the moral track. Despite all of Balaam’s public pieties, after the bribes of Balak, others must have come, perhaps more generous. Finally, the seer’s weakest impulses apparently prevailed. Who knows what excuses he gave himself?

No figure so fully brings to life the warning of Yeshua,

Not everyone who says to me, “Lord, Lord!” will enter the Kingdom of Heaven . . . On that Day, many will say to me, “Lord, Lord! Didn’t we prophesy in your name? . . . Didn’t we perform many miracles in your name?” Then I will tell them to their faces, “I never knew you!” (Matt 7:21–23)

One has to wonder—might he not have been so much more? After the Lord whom he recognized as the true God had revealed the significance of Israel and the blessings they were under, why did Balaam align himself with God’s enemies? The brilliant Franz Rosenzweig, who was about to become a follower of Yeshua, but declined after a Yom Kippur service in which he dedicated himself to Judaism, has another suggestion. Balaam’s error, he says, “was not taking God at his first words: ‘Do not go with them.’ Because the next time God will without fail speak the words of the demon that is within us—‘You may go.’” And there, but for the grace of God, go you and I.

All Scripture references are from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

Buy a Ticket Already!

Everyone knows that simply looking at something cannot cure a deadly snakebite. What healed the Israelites was the power of God, through their display of faith in looking at the serpent raised up by Moses. It’s a testament to God’s character that, despite the lack of faith shown by the Israelites again and again, once they repented, he gave them a means to display faith in him once more, and by it, be saved from certain death.

Parashat Chukat: Numbers 19:1–22:1

Chaim Dauermann, Simchat Yisrael, West Haven, CT

Here’s an old joke you’ve probably heard before: A man desperately wants to win the lottery, as he knows it will solve his profound financial troubles. Every night, he prays to God, asking him to grant him this one, simple request. However, after weeks and weeks of praying, he has not won the lottery, and eventually he becomes despondent. In his anguish, he cries out to God, asking why he has not yet won. In response, a booming voice sounds from the heavens: “So buy a ticket already!” It’s just a joke, but the lesson is a good one: getting help from God doesn’t mean that nothing will be required of us.

All throughout the Torah record, God is revealing himself to humanity, teaching us about who he is. Many of these events have become formative and foundational tales in our culture: Noah’s ark, the crossing of the Red Sea, the Ten Plagues, and the story of Sodom and Gomorrah are but a well-known few. But this week’s parashah, Chukat, features one story about God that would be easy to miss if we didn’t know where to look for it, just one tiny anecdote tucked amidst the more significant-seeming beats of the wider narrative: the story of the bronze serpent.

One thing that the Torah’s wilderness narrative makes clear is that the children of Israel excelled at complaining, and Parashat Chukat is no exception. In Numbers 20, the children of Israel had complained mightily of their lack of water, and in response, God gave Moses some instructions for what to do. He told him merely to tell the rock to provide, but Moses took things a step further, out of his own frustration, and struck the rock with his staff. Although God was ultimately displeased with him, it did not prevent abundant water from gushing forth. There was more than enough to satisfy the needs of the Israelites.

But then, in the next chapter, we hear of yet more grumbling from the children of Israel: “And the people spoke against God and against Moses, ‘Why have you brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness? For there is no food and no water, and we loathe this worthless food’” (Num 21:5).

The food they no doubt referred to was the manna they had in abundance, which by the power of God fell from the sky six days a week (with a double portion before the sabbath) to fulfill all of their nutritional needs. God had delivered them from slavery, provided them food and water time and time again, and had led them to the land he had promised them—which they had failed to enter, out of their own fear—yet still they complained. God was not slow to respond: “Then the Lord sent fiery serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many people of Israel died” (Num 21:6). Desperate for relief, the people appealed to Moses, “‘We have sinned, for we have spoken against the Lord and against you. Pray to the Lord, that he take away the serpents from us.’ So Moses prayed for the people” (Num 21:7).

Although the Bible is mum on the exact meaning of “fiery serpent,” it’s generally understood to be a poisonous snake. (Some have put an even finer point on things, and surmised that these were saw-scaled vipers—snakes which remain plentiful throughout the Middle East, and are the most dangerous in the world. Even today, no anti-venom exists to treat their bite.) Whatever these fiery serpents were, God had a peculiar prescription for relief of their venom: “And the Lord said to Moses, ‘Make a fiery serpent and set it on a pole, and everyone who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.’ So Moses made a bronze serpent and set it on a pole. And if a serpent bit anyone, he would look at the bronze serpent and live” (Num 21:8–9).

Now, anyone knows that simply looking at something, whether a bronze serpent or anything else, cannot cure a deadly snakebite. What healed the Israelites was the power of God, through their display of faith in looking at the serpent raised up by Moses. It’s a testament to God’s character that, despite the lack of faith shown by the Israelites again and again, once they repented, he gave them a means to display faith in him once more, and by it, be saved from certain death. This particular story is instructive because of what it tells us about the nature of God and the redemption he offers us. To put a finer point on it: It’s instructive about the faith he requires of us.

Upon hearing the good news about Yeshua, it’s easy for some to react in an incredulous manner. Just believe, and we are saved? Why would God do something like that? Though it may seem peculiar at first hearing, it is not outside the pattern of God’s character, as we see the exact same process modeled for us, on a smaller scale, in this passage in Chukat: instead of a snake’s venom, think of sin; instead of a bronze model of a serpent, think of the Messiah. In the wilderness, God provided redemption to the children of Israel through the likeness of that which was killing them. So, too, could it be said of his provision of Messiah: “By sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin, he condemned sin in the flesh” (Rom 8:3b).

For the Israelites in the wilderness, it was not quite so simple as looking at the snake and being healed: They had to first repent before God provided them with an antidote to the venom, in the form of the bronze serpent. And then, when looking upon the serpent, they had to believe they would be healed. So, too, must we do when it comes to Messiah: “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9). Or, as Yeshua himself said: “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matt 4:17b).

Perhaps the most famous gospel passage in the world is John 3:16: “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life.” These words of Yeshua testify to the pure and simple gospel message. But it is easier to understand the reality this passage portrays if we keep in mind what Yeshua says in the two verses preceding it: “And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life” (John 3:14–15).

If we are ready to repent, God is ready to save us. All that remains left to do is buy a ticket.

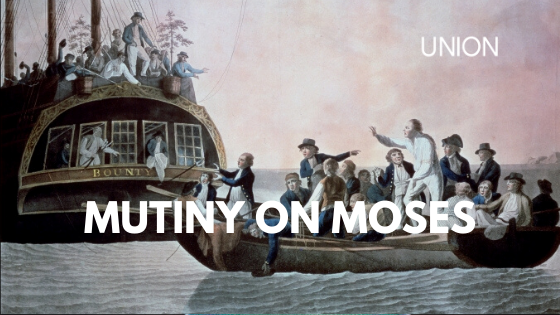

Mutiny on Moses

Ever heard the title Mutiny on the Bounty? On April 28, 1789, Lieutenant Fletcher Christian seized control of HMS Bounty, and set Captain William Bligh adrift in a small boat on the open sea. I mention it here, because we’re looking at one of the Hebrew Bible’s versions of a mutiny—in this case, against Moses not Bligh.

Parashat Korach, Numbers 16:1-18:32

by Dr. Jeffrey Seif

Ever heard the title Mutiny on the Bounty? On April 28, 1789, Lieutenant Fletcher Christian seized control of HMS Bounty, and set Captain William Bligh adrift in a small boat on the open sea. I mention it here, because we’re looking at one of the Hebrew Bible’s versions of a mutiny—in this case, against Moses not Bligh.

This week we’re told Korach (or Korah) “rose up against Moses” (16:1–2a). It wasn’t simply a personal dispute, however. It was political. With a mind to put checks on Moses’ authority, and garner more and more authority for himself and his associates, Korach “took two hundred and fifty men” with him, all of whom were “men of renown” (16:2). “You’ve gone too far! All the community is holy—all of them—and Adonai is with them,” was their battle cry. “Who do you think you are, Moses?” they exclaimed, and “We don’t need you telling us what to do” (paraphrase). The charge closes with a question: “Why do you exalt yourself above the assembly of Adonai?” (16:3). Sounds like a mutiny to me—on the open sand, not the open sea.

The HMS Bounty left England in 1787. The crew had a five-month layover in Tahiti, during which time they settled in and co-mingled with the islanders. Crew members became lax, prompting the captain to impose disciplines on his crew—adjudged to be his prerogative. Chagrined by Bligh’s (mis)management, Lt. Christian rebelled, and the better part of the crew with him. T’was a mutiny! As noted, Captain Bligh was put off on a small boat and set adrift on the open seas. That was Bligh’s situation. What of Moses’ back-story?

Moses had been walking down a rough stretch of highway for some time, before Korach actually took him on. In Numbers 10:11, the people left Sinai and disembarked for Canaan. In 11:1ff, their kvetching over lack of provisions invoked Moses’ ire. In 12:1-2, Moses’ sister Miriam expressed chagrin over her sister-in-law, Moses’ wife. Aaron was drawn into her consternation, and together they uttered a comment that appears later—on the lips of Korach: “Has Adonai spoken only through Moses? Hasn’t he also spoken through us?” (12:2). The Hebrews were restless while en-route to Canaan, and it only got worse when they arrived. Our last parasha, Sh’lach l’cha, told how a reconnaissance mission into Canaan, launched from Kadesh-Barnea, turned into a feasibility study—one with dire consequences (Num 13:1ff). Spies assessed Canaan, and returned with various pieces of information. The spies processed the data but offered unsolicited advice along with it: “we cannot attack these people because, they are stronger than we,” was the upshot of their report (13:31). In sum, Israelites were disconcerted by circumstances they happened upon en-route to Canaan, and they were chagrined by their prospects for success in a soon-coming war with the intimidating Canaanites. “Enough already!” was Korach’s response. He and others believed political change was necessary.

I’ve never commanded a sea-faring vessel, and I’ve never led multiple hundreds of thousands of people through a wilderness. For my part, I’ve been involved in religious leadership for over thirty years. Incessantly taken aback by pressures and problems associated with the rabbinic or pastoral office, I’ve forever read myself as Moses in the Korach story, and Korach and his associates as vociferous associates disinclined to follow my lead. In sum, I refracted the narrative through the prism of my experience and used it to tacitly justify myself and vilify my detractors. Perhaps you have too. Is that fair, though?

Though there are congregational applications, to be sure, the problem I have with reading the passage through my experience now is that it betrays a core hermeneutical principle I hammered as a seminary professor for years: the first interpretation of a passage belongs to the first recipients of it—not the exegete. This is axiomatic. Never mind my context. What was Moses’ context?

Moses wasn’t a rabbi or a reverend attending to the personal one-on-one spiritual needs of one or two hundred people. He wasn’t a religious therapist/counselor. Moses wasn’t tasked with responsibilities associated with building communal consensus to chart paths forward, either. Congregational boards wrestle direction, personnel issues and expenditures, and interact with rabbis and reverends to get it all done. Unlike the reverends and rabbis and boards of today, Moses of yesterday was something of a political leader—much as he was a religious leader. The Mosaic economy he brought forth had a juridical component, one that dealt with a host of criminal and civil mandates. Reverends and rabbis have power to suggest a course of action—not demand it; Moses did, and he actually had power to even effect a death sentence. The Mosaic code imposed mandatory tax burdens, too, in order to support the Levites who were vested with responsibility to manage Israel’s civil affairs and oversee its criminal ones. Rabbis and reverends politely ask for a buck; Moses’ code taxed for it. The ancient world was driven by an agrarian economy, one regulated tightly in the Torah by various Mosaic promulgations. Do reverends, rabbis and boards regulate congregants’ economies? I think not. Some thought Moses took too much power. Korach said as much. Might you have thought or said so, too?

Alighting upon political issues as I close, and not pastoral ones, I am wondering if God’s people would do well to be a bit more respectful toward legitimate, political leaders. My reading of Korach prompts applications to congregational life, to be sure—it can’t help but do that. It also prompts me to advocate for better civil discourse and responsibility, reminding me that we do well to respect those in authority—and so heed the words of the Rabbi from Tarsus, who beckoned us to do just that (Rom. 13:1–7).

This commentary first appeared on UMJC.org, June 21, 2017.

All Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).