commentarY

Ironic Blessings for Tumultuous Times

Our current world situation prompts us to cry, “how long, O Lord, how long?” The promised star out of Jacob has come, yet we still live with war, famine, pestilence, and death. As we walk through these tumultuous times, remember three points drawn from Balaam’s oracles.

Parashat Balak, Numbers 22:2–25:9

Dr. Vered Hillel, Netanya, Israel

The story of Balak and Balaam is one of the most well-known in Numbers, full of irony, fascinating parallels, reversals, patterns of threes, curses and blessings. The Israelites are approaching the end of their forty years in the wilderness. They have already fought and won wars against Sichon, king of the Amorites, and Og, king of Bashan, leaving the Moabites worried about Israel’s advance. Instead of confronting the Israelites in war, Balak summons Balaam. Three times Balak sends messengers to Balaam to entice him to come and curse the Israelites. Twice Balaam refuses. The third time God tells him to go with Balak’s men and to speak only what God commands.

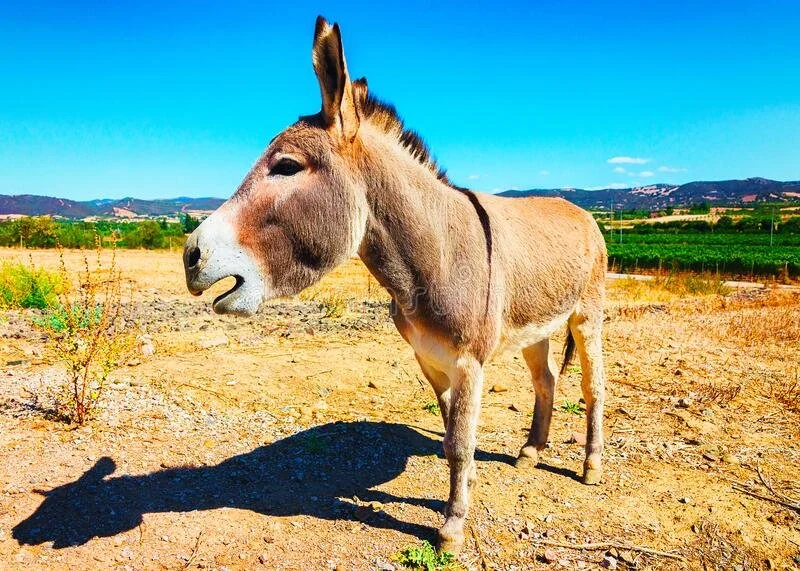

You know the rest of the story: on his way to Moab, Balaam encounters an angel of Hashem, hindering his way. However, only his donkey sees the hindering angel. In the first encounter, the donkey turns off into a field; in the second, it presses against a wall and injures Balaam’s right foot; in the third, it lies down and refuses to move. By the third time, Balaam is so angry that he answers the donkey as if getting into an argument with a donkey is an everyday occurrence. Hashem opens Balaam’s eyes; he sees the angel and falls on his face in repentance. The angel of Hashem charges Balaam to continue to Balak, warning Balaam to say only what he tells him.

Notice the sequence of threes in Balak’s summons of Balaam and Balaam’s encounter with the angel of Hashem. The narrative continues this pattern. From three different vantage points, Balak entreats Balaam to curse Israel. Each time Balaam blesses Israel instead. Just as Balaam gets angry with the donkey, Balak becomes angry with Balaam for not doing what he wishes. Balaam responds to Balak’s anger with a prophecy about the end of days and the coming of Messiah.

Balaam’s three blessings and the prophecy of the end days are exquisite and highly dignified poetry, set in the middle of the narrative and developed with it. Without the narrative, the poetic utterances are almost incomprehensible. The narrative elucidates the allusions to personalities, nations and events in the poetry. For example, in both the narrative and poetry, Balaam’s rise in esteem is inversely matched by the downgrading of Balak. In the first blessing, Balak is called the King of Moab; in the second, he is an ordinary human; in the third blessing and the eschatological/messianic prophecy, Balaam ignores Balak completely.

In the first blessing, Num 22:41–23:12, Balaam explains that Balak, a mortal king, requires him to curse Israel, but the King of kings requires him to bless Israel. Two central themes emerge 1) the election of Israel, which set them apart from all other nations (Num 23:9), and 2) the blessing of their significant number (Num 23:10). These two themes echo the call of Abraham (Gen 12:2), “I will make of you a great nation,” and the blessing of Jacob (Gen 28:14), “Your offspring will be like the dust of the earth.” Balaam says, “Here is a people living alone and not reckoning itself among the nations! Who can count the dust of Jacob or number the dust cloud of Israel?” Balaam’s statement reinforces that Israel alone is Hashem’s am segula, his elected and treasured possession (cf. Exod 19:5).

The second blessing, Num 23:13–26, centers on Hashem’s closeness to Israel and presence in their midst. Balaam no longer addresses Balak as a king but refers to Balak as a mere human with a transitory nature. In contrast, Balaam shows that Hashem is not capricious; he does not alter his purpose. He is the unchanging provider and guardian who accompanies his people Israel in triumphant sovereignty. Israel is invincible with Hashem as their King, like a lion, strong in battle.

The third blessing, Num 23:27–24:9, is characterized by more imaginative and figurative language than the previous two blessings. The Spirit of God comes upon Balaam, and he proclaims, “Ma tovu ohaleicha Ya’acov—How goodly are your tents, Jacob, your dwelling places, Israel!” (Num 24:5–7). This blessing emphasizes the beauty, prosperity, and fruitfulness of Jewish life. Rashi states that the adjective “goodly” in 24:5 refers to Israel’s moral and ethical goodness, and that Balaam is praising the purity and chastity of the Jewish people. The simple meaning of the term encapsulates the full range of perfection—beauty, charm, simplicity, and purity.

Numbers 24:6 and 7 intertwine the motif of water with plant imagery. Biblically, water symbolizes abundance, freshness, and vitality, and plant imagery speaks of upright living. Psalm 1:3 says a righteous man is like a tree planted by streams of water, and Jeremiah 31:11 relates that redeemed Israel is like a well-watered garden and will not languish anymore. The garden imagery connects to the creation of the world and Eden: “And the Lord God planted a garden . . . and made all kinds of trees to grow out of the ground that were pleasing to the eye” (Gen 2:8–9).

Suddenly the poem changes to another type of good—the people of Israel will be exalted over the surrounding nations. This oracle proclaims victory over the enemies of God and his people. The imagery of the lion lying down to rest in peace conjures up a picture of peace as in Lev 26:6: “And I will give peace in the land, and you will lie down, and none will make you afraid.” Furthermore, the blessing concludes, “blessed is everyone who blesses you and cursed is everyone who curses you” (Num 24:9), pointing back to Balaam’s first blessing and those of Abraham (Gen 12:3) and Jacob (Gen 27:29).

In one final ironic twist, Balaam curses Israel’s enemies (Num 24:10–25) and prophesies that Israel will crush the surrounding nations and be blessed while the other nations will be doomed.

These verses encapsulate a well-known messianic prophecy: “I see him, but not now: I behold him, but not near—a star shall come out of Jacob, and a scepter shall rise out of Israel” (Num 24:15–19). Jewish and Christian interpreters understand this verse to refer to a future ruler of Israel. Jewish interpreters see a reference to King David or Bar Kochva, who led a revolt against Rome in the second century CE, and Christian interpreters see Yeshua. However, neither interpretation completely fulfills the prophecy. We still look forward to the days when all the enemies of God and his people will be subdued and put under his feet, and when war, famine, pestilence, and death will be conquered.

Our current world situation prompts us to cry, “how long, O Lord, how long?” (cf. Hab 1:2). The promised star out of Jacob has come, yet we still live with war, famine, pestilence, and death. As we walk through these tumultuous times, remember three points drawn from Balaam’s oracles. God is the sovereign King who will complete what he began, the invincible and unchanging guardian who lives among his people, and the victor who will subjugate all his enemies under his feet and bring peace. May we live uprightly like a tree planted by streams of water and like a well-watered garden that in the kingdom of God produces abundance, thirty, sixty, and a hundredfold (Mark 4:8, 20)!

Does the Torah Teach about an Afterlife?

“Christians worry about eternal judgment and whether they’ll go to heaven or hell when they leave this world. Jews are concerned about life in this world, and how to make it a better place while they’re here.”

Parashat Chukat, Numbers 19:1–22:1

Russ Resnik, UMJC Rabbinic Counsel

“Christians worry about eternal judgment and whether they’ll go to heaven or hell when they leave this world. Jews are concerned about life in this world, and how to make it a better place while they’re here.”

I’ve heard this sort of comparison many times, and there’s some truth to it. Christianity does emphasize the afterlife more than Judaism does, and Judaism does focus more on this life and how to live redemptively within it. But even a quick look at traditional Judaism reveals that it has plenty of concern, and lots to say, about the life to come. In one of our earliest post-biblical texts, Rabbi Jacob says, “This world is like an antechamber before the World to Come. Prepare yourself in the antechamber so that you may enter the banqueting hall” (Avot 4.21, Koren Siddur).

Still, it’s true that there’s very little about the afterlife in the Torah itself, the text upon which the whole edifice of Jewish thinking rests. One early Jewish text responds to this fact by declaring that anyone who says the teaching about resurrection doesn’t derive from the Torah has no share in the world to come (m. Sanhedrin 10.1). One scholar notes,

The insistence, against the plain sense of the text, that the Torah asserts the resurrection of the dead, is an indication of the importance that the rabbis attach to the belief, while the threat of losing one’s portion in the world to come for rejecting not the belief itself, but rather the claim that it comes from the Torah, presumably reflects some anxiety about its derivation. (Martha Himmelfarb in The Jewish Annotated New Testament)

I won’t argue about whether our sages felt “some anxiety about” deriving belief in the resurrection from the “plain sense” of Torah, but I’ll be happy to consider a hint of life beyond this life in this week’s parasha:

And the people of Israel, the whole congregation, came into the wilderness of Zin in the first month, and the people stayed in Kadesh, and Miriam died there and was buried there. And there was no water for the congregation, and they gathered themselves against Moses and against Aaron. (Num 20:1–2)

The water runs out after Miriam dies and our sages conclude that Israel’s supply of water in the wilderness depended on the merit of Miriam, Moses’ big sister, who was instrumental in saving his life as a baby (Exod 2:1–10) and later became a prophetess and leader herself (Exod 15:20–21), although not without flaws, like her two brothers (Num 12).

Miriam lives on after her death through her legacy, but of course, that’s hardly a share in the world to come, or the sort of resurrection the rabbis are discussing in Sanhedrin 10.1. But there’s a clue of something more in the wording here: “Miriam died there and was buried there.” Why does “there,” or sham in Hebrew, appear twice, when it could have simply said, “Miriam died and was buried there”? The word “there/sham” points ahead to a second death in our parasha. When the time for Aaron’s death comes, the Lord tells Moses to bring him and his son Eleazar to Mount Hor. “And Aaron shall be gathered and die there.”

Moses did as Hashem commanded. And they went up Mount Hor in the sight of all the congregation. And Moses stripped Aaron of his garments and put them on Eleazar his son. And Aaron died there on the top of the mountain. (Num 20:26b–28a, emphasis added)

“There” is a common word, of course, but it’s striking that it is again repeated unnecessarily. We’ve already been told that Aaron shall “die there” on Mount Hor, and then we’re told again that “Aaron died there on the top of the mountain.” The sages see in this repetition a connection between the deaths of Aaron and Miriam so that the details of Aaron’s death apply to Miriam as well.

Aaron doesn’t just die, as we’re told of Miriam, but “shall be gathered and die there.” This gathering is described more fully several times in the account of our forefathers in Genesis. Abraham dies and is “gathered to his people” (Gen 25:8), as are Isaac (35:29), Jacob (49:33)—and even Ishmael (25:17). I’ve heard this phrase explained as a reflection of ancient burial customs, in which the recently deceased corpse is placed in a tomb until the flesh decomposes. Then the bones are placed in an interior chamber of the tomb where the bones of the ancestors lie, thus being “gathered to his people.” But something different seems to be going on here. Back in Genesis, Jacob was gathered to his people well before his body was returned to the land of Canaan and the ancestral burial site. Likewise, Aaron isn’t literally gathered to his people, and the same is true of his brother Moses, who dies soon after Aaron. When the time comes, Hashem tells Moses,

“Go up this mountain of the Abarim, Mount Nebo. . . . And die on the mountain which you go up, and be gathered to your people, as Aaron your brother died in Mount Hor and was gathered to his people.” (Deut 32:49–50)

Aaron was gathered to his people on Mount Hor, but no ancestors were buried there—in the plain sense of Scripture he was not literally gathered to his people. This is even more evident with Moses:

So Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab, according to the word of the Lord, and he buried him in the valley in the land of Moab opposite Beth-peor; but no one knows the place of his burial to this day. (Deut 34:5–6)

Here’s another superfluous “there/sham.” The text could have simply said, “So Moses the servant of the Lord died in the land of Moab,” but “there/sham” links his death to the deaths of his siblings Miriam and Aaron. They’re all gathered to their people, not through an ancient burial custom, but through joining their forebears in another realm, in a life beyond this one.

It’s possible that the phrase “gathered to his people” simply means joining them in death without any reference to life beyond death. But Messiah Yeshua draws upon the words of Torah to make the teaching about the afterlife more explicit.

“But that the dead are raised, even Moses showed, in the passage about the bush, where he calls the Lord the God of Abraham and the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob. Now he is not God of the dead, but of the living, for all live to him.” (Luke 20:37–38)

“All live to him.” There is life beyond this life, life in God, and the Torah itself testifies of it.

We must admit, though, that this testimony is not as explicit as we might think it deserves. One can read through the whole Torah and miss its promise of the afterlife. Why is this so? Perhaps the Torah is providing a balance between focusing on the afterlife to the point of neglecting real life in this world and, on the other hand, denying any afterlife at all. The assurance of life to come gives us courage and hope in this life, and at the same time remains mysterious and undefined enough to avoid diverting our attention from this world and our assignment within it. As the sages say,

This world is like an antechamber before the World to Come. Prepare yourself in the antechamber so that you may enter the banqueting hall.

Scripture references are from the English Standard Version (ESV) adapted by the author.

I've Met Korah

Leadership can be brutal. Many may be initially intoxicated with the idea of leading others, but give it a few weeks, months, or years, and one will encounter challenges. One of the most difficult aspects of leadership is when a friend, partner, or associate comes against you, and you experience betrayal.

Parashat Korach, Numbers 16:1–18:32

Barri Cae Seif, Sar Shalom/Prince of Peace, Arlington, TX

Leadership can be brutal. Many may be initially intoxicated with the idea of leading others, but give it a few weeks, months, or years, and one will encounter challenges. One of the most difficult aspects of leadership is when a friend, partner, or associate comes against you, and you experience betrayal. Betrayal can occur within a marriage, within a business partnership, within the corporate environment, and within ministry.

Not only is betrayal painful, it also severs relationships. Some relationships may have been fostered for years or decades, and yet they can be destroyed within a short while. Jealousy within an organization can truly bring havoc. I’ve walked through this experience of betrayal myself. Rather than address the issues head on, I chose to ignore and overlook indiscretions until it was too late. It really doesn’t matter if you are Moses, Abraham, or Yeshua, betrayal is going to occur, and jealousy will raise its ugly head against you.

As we look at the opening of Numbers 16, we see that Korah had been scheming behind the scenes against Moses and Aaron. Korah had one question for Moses: “Who do you think you are?! Who made you God, why do you exalt yourself above the assembly of the Lord?” Moses was from the tribe of Levi, and he was chosen by God to lead. Every leader needs to be sure that God has called them into that place of leadership. I always saw myself as an excellent follower. I never wanted leadership. However, when God called me into a leadership role years ago, I knew that it was his call upon my life and not my own. Followership is important in any realm of life, and the most important followership that any of us can have is to follow Yeshua, our Messiah.

Korah, however, had his own ideas about how things should be run. He assembled 250 council appointees who were in one accord with him. This was a conspiracy to accuse Moses of exalting himself above God.

They assembled against Moses and Aaron. They said to them, “You’ve gone too far! All the community is holy—all of them—and Adonai is with them! Then why do you exalt yourselves above the assembly of Adonai?” (Num 16:3 TLV)

As I continue to read through Numbers 16, I can say that I’ve met Korah.

When I read this passage, I still get riled up. I’ve been in this position. Moses fell on his face after these accusations (16:4). Although I did not fall on my face when I was falsely accused, I could feel overwhelming sorrow grow in my heart. I still get sad. As I tried to support my answers with documentation, my critics had already made up their own minds. They knew better than I, and they wanted control.

Pride can take over an organization. Pride can motivate individuals to do things that they normally would not do. Pride can draw people together, especially if they desire to conspire against a leader. I have been there. I’ve experienced it first-hand. After a few days of prayer, along with ten days of fasting from social media, etc., I knew that I needed to walk away from the organization that I’d birthed. One of the valuable helps in walking through this crisis was a book by Anne Graham Lotz, Wounded by God’s People. Lotz writes:

Rejection, disapproval, or abuse by God’s people can be devastating because if you and I are not careful, we may confuse God’s people with God. And God’s people don’t always act like God’s people should. The way you and I handle being rejected and wounded is critical. Our response can lead to healing . . . or to even more hurt. (Kindle ed., loc. 259)

There is a cost to leadership. We learn about Moses’ humility as he walks through this trial. It’s one thing to endure pain that is physical, but it’s another thing when those who were your friends turn on you. Moses did not decide this issue within his own ability. He turned the test over to God.

Then he said to Korah and all his following saying, “In the morning Adonai will reveal who is His and who is holy. The one whom He will let come near to Him will be the one He chooses to come near to Him. Do this, Korah and your whole following! Take for yourselves censers. Put fire and incense into them in the presence of Adonai. Tomorrow the man that Adonai chooses will be the holy one! You sons of Levi are the ones who have gone too far!” (Num 16:5–7)

We then read about the showdown. Korah, Dathan, and Abiram brought firepans before the Lord, and Moses “warned the assembly saying, ‘Move away from the tents of these wicked men! Don’t touch anything that is theirs, or you will be swept away because of all their sins!’”

So they moved away from near the dwelling of Korah, Dathan and Abiram. Dathan and Abiram came outside and were standing at the entrance of their tents with their wives, their children, and their little ones.

Moses said, “By this you will know that Adonai has sent me to do all these works, that they are not from my own heart. If every one of these men die a common death and experience what happens to all people, then Adonai has not sent me. But if Adonai brings about a new thing, and the earth opens her mouth and swallows them and everything that is theirs, and they go down alive into Sheol, then you will know that these men have despised Adonai.” (Num 16:26–30)

My guess is that Korah, Dathan and Abiram had no idea that they would soon suddenly perish, but as soon as Moses finished saying these things, the ground split under them.

The earth opened its mouth and swallowed them, along with all their households, all of Korah’s people and all their possessions. They went down alive into Sheol, they and everything that was theirs. The earth closed over them, and they were gone from among the community.

All Israel around them fled at their outcry, for they shouted, “Perhaps the earth will swallow us!”

Fire also came out from Adonai and consumed the 250 men offering the incense. (Num 16:32–35)

There is a point in ministry leadership when we realize have to turn it all over to God. As we approach our battles, we can acknowledge our weakness. “I have been crucified with Messiah! It is no longer I who live but Messiah lives in me. And the life I now live in the body, I live by trusting Ben Elohim, who loved me and gave Himself up for me” (Gal 2:20). We surrender our finiteness into the hands of Infinite God and wait on Him, to bring forth His perfect results.

We believers in Yeshua are so blessed because we can turn to God’s word and receive comfort. The Ruach HaKodesh, the Holy Spirit, will lead us into all truth. What great encouragement we receive from Hebrews 12:3: “Consider Him who has endured such hostility by sinners against Himself, so that you may not grow weary in your souls and lose heart.”

When we go through these challenging times, we can rest assured that the Lord is in control. What a comfort! What joy! We can trust Him to give just enough light for the next step. He is our Rock of Refuge, and we can trust Him.

All Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

Follow Fear or Follow Faith?

Moses sends out twelve men, a man from every tribe, “every one a leader among them,” to spy out the land. This action reveals the partnership between God and his people that marks all of our godly activities here on earth: We follow God’s word to do his work, yet we also have to prepare by developing intelligent plans. Herein lies our dilemma.

Parashat Shelach L’kha: Numbers 13:1–15:41; Haftarah: Joshua 2:1–24

Rachel Wolf, Congregation Beth Messiah, Cincinnati

In last week’s portion, Beha’alotkha, the people of Israel, following the cloud of the Lord, moved for the first time, after more than a year, from the Wilderness of Sinai. There they had heard the voice of God from the Mountain and, as one people, had sincerely proclaimed fidelity to God’s covenant. However, Fear quickly led them to desperately seek solace in other (more manageable) gods, like the calf of gold. After the glorious descriptions in Beha’alotkha of the tribes and the Mishkan departing the camp at Sinai in beautiful order, there is almost immediate complaining and weeping. Fear has struck again, causing all manner of discontent and accusations.

In this week’s portion Israel has moved on to the Wilderness of Paran. The location of Paran is not certain but seems to be on the west side of the Gulf of Aqaba, southwest of Eilat. Here we are at a crossroads. Moses is making preparations, per God’s instructions, to enter and conquer the Land of Israel’s inheritance.

The Twelve

In chapter 13, Moses sends out twelve men, a man from every tribe, “every one a leader among them,” to spy out the land. This action reveals the partnership between God and his people that marks all of our godly activities here on earth: We follow God’s word to do his work, yet we also have to prepare by developing intelligent plans. Herein lies our dilemma. Because we are charged with practical and creative responsibility, it is often hard to know how, or where, faith comes into the picture. It is easy to take on the responsibility, not only for planning and doing, but for the outcome.

When the twelve return, they all agree it is a good land. But, having seen the inhabitants of the land, ten of them allow themselves to retreat into Fear. They fear the unknown; they assess their inadequacy to do the job; and they blubber that this whole “leaving Egypt” idea was a big mistake.

But it’s worse than that!

Remember: every one of these men are the chosen, respected “leaders among [the tribes].” Not only do they quickly retreat into Fear, they exaggerate the dangers and by their report bring “all the congregation” into such a fearful state that the people weep all night and decide to choose a leader who will take them back to Egypt! (14:1–4).

I want to say something here about the importance of young leadership. At this point, Moses and Aaron simply fall on their faces (14:5), presumably praying. But I suspect they are also totally exhausted by the continuous complaining and inability of the people to believe God and bear with some difficulties.

This is when Caleb and Joshua step up, take the helm, and speak up. They tear their clothes in the traditional act of mourning and repentance, and then speak forcefully to the people not to fear (14:6–10). Unfortunately, they could not unearth the quickly sprouting seeds of fear that had been recklessly sown by the ten. God had to step in. But these courageous young leaders continued to serve Moses and the people of Israel until they entered the Land.

The fateful consequence of following Fear is that none of the “fear generation” enter the land of promise. In addition, they sentence their children and grandchildren to 40 years of wandering in the wilderness.

Now, let’s look at the Second Round of Spies, in our Haftarah portion, Joshua 2.

Forty years later, poised to enter the Land, Joshua, now in top leadership, sends, this time, two spies (it seems Joshua learned something from his previous intelligence gathering experience) to check out the situation at Jericho. The spies meet Rahab, a woman who lives right at the wall of the city and seems to be somewhat of a busybody—up on all of the news! She tells these two Israelites that the “terror of the Israelites and their God has fallen on the people of the land” and they are all faint-hearted. She hides the two spies, shows them kindness, and works out a deal with them to preserve her family when they come back to destroy the city. The ten spies in Shelach L’kha let Fear control them when they saw the sheer size of the giant Anakites. With hindsight we can now see that the fear of the Lord had fallen on the inhabitants of the land, giving the Israelites a significant advantage.

Rahab feared, but her fear led her to faith in the God of Israel.

Had the ten leader-spies forty years earlier controlled their natural human emotion of fear, and allowed themselves to be encouraged by the faith of Joshua and Caleb (surely the twelve conferred together as they trudged back to Paran), the outcome would have been quite different. They would have had to fight, but God knew that fear would become their ally instead of their mortal enemy. He, himself, would cause the hearts of the people dwelling in the land to “melt with fear,” as the story of the exodus spread abroad.

As we focus on God’s Word, and allow ourselves to be encouraged by those blessed with positive faith, we can turn our fears into faith in God’s goodness and into positive action. Fear is a malicious and miserly taskmaster. To give in to fear is to retreat into helplessness, to use our God-given imagination against ourselves. God desires that we partner with him with faith in his faithfulness. This will, at times, entail enduring suffering, but it is the only way to achieve his best in and for us.

In my experience this is easy to understand but quite a bit harder to actually accomplish, especially as the world grows dark around us. We are creatures who naturally seek safety for ourselves and for our loved ones. There are no pat answers. Yeshua, in Luke 21, exhorts us to stay alert and aware, yet to realize that “when these things begin to take place, straighten up and raise your heads, because your redemption is drawing near.” And as we approach the period of the haftarot of rebuke and consolation, we can join together, with our ancestors, and feed our imaginations with the sublime words of Isaiah:

Arise, shine, for your light has come,

and the glory of the Lord has risen upon you.

For behold, darkness shall cover the earth,

and thick darkness the peoples;

but the Lord will arise upon you,

and his glory will be seen upon you. (Isa 60:1–2)

Called to Bring Light

Finally, after so many months remaining in the shadow of Sinai, Moshe will at last be leading God’s people toward the promised land. But just as Israel’s story is about to unfold in new ways, this parasha provides some reflective insights for us to consider.

Parashat Beha’alotkha, Numbers 8:1–12:16

Ben Volman, UMJC Vice President

Finally, after so many months in the shadow of Sinai, Moshe will at last be leading God’s people toward the promised land. But just as Israel’s story is about to unfold in new ways, this parasha provides some reflective insights for us to consider.

Parashat Beha’alotkha begins with the opening instructions for Aaron concerning the menorah, that unique lampstand to light the first interior room of the Tabernacle. What did it look like? Perhaps the most memorable image of the lampstand was carved from stone on the victory Arch of Titus in Rome. Even today, after 2000 years, it clearly depicts the Romans celebrating their plunder from the burnt remains of Herod’s Temple—the menorah at the center.

Both the opening of our Torah passage beginning in Bamidbar (Numbers) 8 and the haftarah reading in Zechariah 2:14–4:7 highlight something extremely important: the intentional identification of Israel’s spiritual leadership with the menorah. Aaron has just watched while the princes of the nation presented bountiful gifts for the service and worship of Hashem. Aaron could never have matched their largesse, but as if in consolation, Rashi tells us, “The Holy One, Blessed Be He, said to him, “Your part is of greater importance than theirs, for you will kindle and set in order the lamps.’”

Aaron’s specific task here is to focus the light of the lamps forward, which he does exactly as required, and we’re reminded that the menorah was hammered out of gold precisely according to the pattern given to Moshe by Hashem (Num 8:4). The moment is one of complete harmony in the relationship between God, Israel, and the High Priest. The midrashim on this passage include Israel’s questioning why the “the Light of the world” would need a lampstand in the place of his holy presence. The reply comes: “Not that I require your light, but that you may perpetuate the light that I conferred on you as an example to the nations of the world.” The answer perfectly reflects Isaiah 60:2ff: “Nations will go toward your light / and kings toward your shining splendor.” Aaron’s legacy as the first High Priest will be to remind those who follow him that, in spite of all the ways they may fall short, their calling is still to be the living embodiment of inspiration, hope, and vision both to Israel and eventually “a light to the nations” (Isa 49:6).

The haftarah portion, describing the dream visions of Zechariah, also sheds light on the difficult but high calling of Israel’s spiritual leaders. The young prophet is determined to inspire his community: the returned exiles from Babylon who are resisting the call of their leaders—Yehoshua the High Priest and the Jewish governor, Zerubavel—to rebuild the Temple. The people are discouraged by years of poor harvests and a depressed economy. But the great task can only be done together.

Zechariah’s visions in chapter 3 affirm God’s choice of Yehoshua as Israel’s worthy High Priest and in the final vision of the haftarah in chapter 4, there is a word from the Lord for the governor, Zerubavel. The prophet sees the great sign of a golden menorah surrounded by two olive trees. The menorah is a symbol of promise that the lights of the Temple will be rekindled, and these men, inspiring and challenging the people of God, have been given the task by God’s anointing: “Not by force, and not by power, but by my Spirit,” says Adonai-Tzva’ot (Zech. 4:6). That remarkable visionary phrase sums up the challenge of true godly leadership. We find our way forward not by our force of will but guided in the light of the will of God.

Yeshua, our ultimate and true Kohen HaGadol, also brings us back to the significance of God’s leading us in the light. As Yochanan (John) wrote in the opening words of his Besorah, “In him was life, and the life was the light of mankind. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not suppressed it” (John 1:4–5). This is the light of his Spirit that equips each one of us who follows him: “If we are walking in the light, as he is in the light, then we have fellowship with each other, and the blood of his Son Yeshua purifies us from all sin” (1 John 1:7).

In each of these settings, from Aaron to the post-exilic struggles to rebuild the Temple to Yeshua himself, we see how leadership among God’s people is both perilous and inspiring. Criticizing leaders and tearing at the foundations of a community isn’t hard. But we are called to build each other up, as Kefa (Peter) calls us “living stones . . . to be cohanim set apart for God” (1 Kefa 2:5). When we go through challenging times it can be hard not to lose heart. Part of that task is building up our servant-hearted leaders. I often reflect that no one truly knows the price that someone has paid to carry out a faithful ministry except the one who has been called.

The humble but symbolic service of Aaron to the menorah—and the calling to bring light and be a light to our family, our community, and our greater family in the faith—brings us back to our true higher purpose no matter what the circumstances. I was commenting to a friend the other day how my mentor, Rev. Dr. Jakob Jocz, could not possibly have imagined how the next generation would take up the vision of our Hebrew Christian forebears. He was a committed Anglican who loved the church—but he encouraged and inspired me, and I know that he would not ever tell us turn back from our Messianic Jewish vision. We must follow where the light, the Spirit, and Yeshua are directing us and uphold the good leaders who are paying the price for leading the way.

Patiently, no matter the circumstances, as we wait on God we will see the light break through. And even the darkness will have served its purpose. I think of that moment when the new State of Israel sought a symbol for their emblematic seal. They chose the menorah—distinctively surrounded by two olive branches: now a familiar image on coins, stamps and Israeli passports. And where did they find an authentic model for such an auspicious symbol? It was taken from the image embedded on the Arch of Titus waiting for the promise of Israel to be reborn.

Bible quotes are taken from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

Face-to-Face with the Eternal

Is it possible to have a face-to-face conversation with God?

In Exodus 25:22, the Lord said that he would speak to Moses “from above the ark-cover, from between the two k’ruvim [or Cherubim] which are on the ark for the testimony.”

Parashat Naso, Numbers 4:21:1–7:89

Daniel Nessim, Kehillath Tsion, Vancouver, BC

Is it possible to have a face-to-face conversation with God?

In Exodus 25:22, the Lord said that he would speak to Moses “from above the ark-cover, from between the two k’ruvim [or Cherubim] which are on the ark for the testimony.” We are also told in Exodus 33:11 that “Adonai would speak to Moshe face-to-face, as a man speaks to his friend.” That seems to flatly contradict what is said in Exodus 33:20: “a human being cannot look at me and remain alive.” Was Moses an exception to the rule? Is it possible for some people and not others to see God and live? How did this work and does it mean anything for us today?

The answer is in our parasha, Naso. Here we find a brief statement between the list of offerings of the leaders of the twelve tribes and the Lord’s instructions concerning the menorah inside the tent of meeting: “When Moshe went into the tent of meeting in order to speak with Adonai, he heard the voice speaking to him from above the ark-cover on the ark for the testimony, from between the two k’ruvim; and he spoke to him” (Numbers 7:89).

This statement gives us a number of insights:

First, Moshe would initiate the conversation, as we read, “When Moshe went into the tent of meeting in order to speak with Adonai.”

Second, the conversation was within the tent of meeting, not specifically the inner sanctum, the Holy of Holies.

Third, Moshe was close enough to tell exactly where the voice was coming from, as “he heard the voice speaking to him from above the ark-cover on the ark for the testimony, from between the two k’ruvim.”

As Rashi comments, “When two Scriptural verses apparently contradict each other there comes a third and reconciles them.”

This week’s parasha tells us exactly how God would speak to Moses. There was a space between the wings of the cherubim, the holy angels above the Ark, and it was from between their outstretched wings that the voice of the Almighty was audible to Moses. Moses, on the other side of the parochet, the veil, did not actually see God, and there is no indication that the source of his voice was visible. The term “face-to-face” was clearly an expression of speech. Still, Moses talked with God!

As human beings we want interaction. As helpful as video services such as Zoom are, they can’t replace face-to-face conversation. Yet of all Israel, only one person was able to actually talk to Hashem “face-to-face.” What is more, that person was only able to talk to him in one place. After that one person died, there is no record of any other Israelite talking to God face-to-face like this. We could theologize about it and say that this distance is one of the consequences of our expulsion from Gan Eden, the Garden of Eden. But the events in Naso come well after we were cast out from that place where God would walk and talk with Adam and Eve in the cool of the day.

So there is both something astonishing and wondrous about Moses speaking to Hashem. It is almost as if the curse had been rolled back a little bit, and even if just with this one man, and in this one place, God and man were once again talking face-to-face. The Tent of Meeting had just been completed. The venerable leaders of each of twelve tribes, excluding the Levites, had just given their offerings. Now, in the Tent of Meeting, Moses was meeting God.

We might think that it would have been wonderful if this custom had continued, perhaps through the Aaronic priesthood, to this day. The fact that it hasn’t gives pause for thought.

In Midrash Rabbah Rabbi Azariah tells a parable in the name of Rabbi Judah ben Simon:

There was an earthly king who had a dearly loved daughter. While she was small, he would speak with her publicly, but when she grew up as a woman, he realized that he needed to be more discreet, as talking to her in public was not suitable to her dignity. So he made a pavilion where he and his daughter could meet and talk.

In the same way, there is the sense that in God’s love for Israel, there was a time in the Garden when he could speak with us openly, but the time came when a more private, fitting place had to be made. That was the “pavilion” of the Tent of Meeting, the Tabernacle. Israel, as a maturing child, was being given a permanent way in which to know her father was present and available to talk.

Like Moses, we are welcome to approach the Eternal on our own volition. There is no requirement that we wait for a summons. The Eternal is always there. Messiah, we are told in Hebrews 10:20, has not only made a way for us, but has made a way beyond the parochet so that there is no barrier between us and the voice of the Eternal. Some traditions say that voice was very quiet, and only Moses with his acute hearing could make out what was being said to him. Other traditions say the voice was majestic, as the voice from the mountain of God in the wilderness, but that only Moses could hear it. The priests outside heard nothing.

If we are able to enter the holiest place, past the parochet, can we hear the voice of God, whether a quiet whisper or a majestic, thunderous roar? Can we today discern exactly where that voice is coming from? Perhaps, as with Moses, the secret is to have a special place, a quiet place free from the distractions of the world around us. Perhaps in that special place, as with the Tent of Meeting, there is a way for us to meet with the Eternal.

All Scripture citations are from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

Numbers, Shavuot, and Lifting Up Your Head

The book of Numbers begins with God telling Moses to take a census of the entire assembly of Israel. This census seems to appear out of nowhere. Which leads us to ask, what is the purpose of this census anyway?

Shavuot/ Parashat Bamidbar, Numbers 1:1-4:20

Rabbi Joshua Brumbach, Simchat Yisrael, West Haven, CT

The Book of Numbers begins with God telling Moses to take a census of the entire assembly of Israel. This census is where the book of Numbers gets its English name.

Take a census of the entire assembly of Israel according to their families. (Numbers 1:2)

This census seems to appear out of nowhere. Right at the very beginning of Numbers, God commands this census to be taken. Which leads us to ask, what is the purpose of this census anyway?

The Hebrew of the text helps provide an answer, as the phrase se’u et rosh (שְׂאוּ אֶת-רֹאשׁ), which we usually translate as “take a census,” is more literally “lift up the head.” The Hebrew paints a more nuanced picture than that of a person with a clipboard simply going around and counting people. Instead, the more literal reading, “lift up the head,” implies a selection involving dignity and respect. According to Hasidic thought, the purpose of the census was to reach out to the core of the Jewish soul, because when each person is counted, everyone is equal. Each person counts as only one count. No one is counted twice, and no one is skipped. The census evens the playing field and shows the equality and value of every single individual.

Following the census of the people in chapter one of Numbers, the Torah then turns its attention in chapter two to how the Israelites were to set up camp around the Tabernacle. The 13th century Jewish sage, Ramban (Nachmanides), noticed clear parallels between the specific commandments regarding the Tabernacle and the Revelation at Sinai. According to Ramban, as Sinai represented the place of God’s manifest presence, so too the Tabernacle represented God’s presence on earth. And just as the people camped around the base of Mt. Sinai, so too did the tribes camp around the Tabernacle, symbolizing the centrality of God’s presence among the people of Israel. Therefore, by making the Tabernacle central to the people of Israel, geographically and conceptually, it also solidified the Jewish commitment to the centrality of Torah.

This coming Saturday evening marks the beginning of Shavuot, also known as Pentecost, or the Feast of Weeks. It is the holiday when we celebrate the giving of the Torah at Mt. Sinai. According to Abraham Joshua Heschel, something extraordinary took place there between God, Moses, and the Jewish people:

What we see may be an illusion; that we see can never be questioned. The thunder and lightning at Sinai may have been merely an impression; but to have suddenly been endowed with the power of seeing the whole world struck with an overwhelming awe of God was a new sort of perception. . . . Only in moments when we are able to share in the spirit of awe that fills the world are we able to understand what happened to Israel at Sinai. (God in Search of Man, 195–197)

Every year on Shavuot we seek to re-experience a taste of the awesomeness of what happened at Sinai. And as a Messianic Jewish community, we also celebrate the incarnation and indwelling of the Living Torah, Yeshua our Messiah, and the affirmation of his incarnation, resurrection, and ascension through the outpouring of God’s Spirit as described in Acts 2.

After all, Shavuot is the important context for understanding Acts 2 when the Spirit was poured out upon those early Jewish believers in fulfillment of God’s promise of restoration (Jeremiah 31, etc.). Furthermore, this outpouring of the Spirit was so they could go out and do. This infilling was not just for their own spiritual edification, but to empower them to do the work of the Kingdom.

Although one of the roles of the Spirit is to serve as a “comforter” (John 14:16–17, 26) the Spirit also empowers and enables us to observe his covenant (see especially Ezekiel 36:26-27). Furthermore, the Spirit also prepares us for our divine mission, because, as believers in Yeshua, our role must be to help implement God’s kingdom of justice now: through our life, through our deeds, and to all those around us. We must be about the work of preparing the way for our Redeemer.

Shavuot is not just when the Jewish people received our calling and instructions for how to live as Jews, Sinai was also a moment of dignity, when God took us, an enslaved and defeated people, and lifted our heads and spoke purpose into us. And God, through the gift of his Spirit, can do the same for everyone today who seeks him.

The census at the beginning of the book of Numbers and the giving of the Torah on Shavuot both have important lessons for us today. They both were about providing direction and purpose. May you also experience renewed dignity and purpose this Shavuot. May the Lord raise up your head, impart dignity and purpose to you, and pour out his Spirit upon you in a fresh and powerful way.

Chag Sameach … have a wonderful Shavuot!

The Joy of Dispossesion

Recently a friend of mine was helping her friend pack and get ready to move, and found this handwritten Post-it note on a bookcase: “If God is all we have, that is all we need.” She commented, “Hmmm . . . but we all have a lot more. Maybe we don’t need it all?!”

Parashat B’chukotai, Leviticus 26:3–27:34

Rabbi Russ Resnik, UMJC Rabbinic Counsel

Recently a friend of mine was helping her friend pack and get ready to move and found this handwritten Post-it note on a bookcase: “If God is all we have, that is all we need.” She commented, “Hmmm . . . but we all have a lot more. Maybe we don’t need it all?!” That’s a question bound to arise when you’re moving a whole household—and also as we listen to this week’s parasha, which returns to the discussion of the laws of jubilee that started last week.

“If God is all we have, that is all we need” is a great lead-in to this whole topic and its message for today, especially one big idea that I’ll call the joy of dispossession.

Let’s start with a review of the basic instruction from last week’s parasha:

And you shall consecrate the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you, when each of you shall return to his property and each of you shall return to his clan. (Lev 25:10)

The return to one’s original land grant and family limited the accumulation of wealth, a limitation that we might want to think about in 2022, when the wealthiest 1% in America holds 40% of all the wealth in this country. Globally, the top 1% holds 50% of all wealth. This imbalance is increasing in our current global economy, and more wealth brings more power, including power to dominate and control others. Hashem blocks this sort of accumulation of wealth among his people, not through elaborate regulation and bureaucracy, but through a simple rule: “The land shall not be sold in perpetuity, for the land is mine. For you are strangers and sojourners with me” (Lev 25:23).

This principle makes for a healthier and freer society, with a vision, not of boundless accumulation, but of hardy self-reliance, where everyone sits under his own vine and fig tree (Mic 4:4). As Rabbi Hillel observed long ago, “the more possessions, the more worry” (Avot 2:7). In our age of consumerism, an age that elevates greed into a virtue, we need to rediscover the joy of dispossession. We spend our energies worrying about what to acquire, and how to acquire it, but in the end, what we acquire threatens to possess us, as Hillel noted. The principle of dispossession relieves us of such preoccupations, and has the potential to draw us closer to God.

In the jubilee, each Israelite gets to return to their original holding and family, even if they’ve been sold into bondage: “For it is to me that the people of Israel are bondservants. They are my bondservants whom I brought out of the land of Egypt: I am Hashem your God” (Lev 25:55). The land belongs to God, not to us, or to anyone that we might want to sell it to, and in the same way, we ourselves belong to God. The principle of dispossession includes not only our property but also our own selves—so that we’re free to belong to him.

In most years (although not this year), we read the two parashiyot of Leviticus, B’har and B’chukotai, together as one week’s portion, and both take place in the same physical setting. B’har opens, “And the Lord spoke to Moses on Mount Sinai . . .” (Lev. 25:1). B’chukotai (and the entire book of Leviticus) concludes, “These are the commandments which the Lord commanded Moses for the children of Israel on Mount Sinai” (27:34). Gathered at Mount Sinai, the Israelites receive a final set of instructions before they depart for the land of promise. No one imagined at this time that thirty-eight more years of wandering lay ahead. Instead, these instructions were to be the final orders before Israel entered its inheritance. At this crucial moment, as Israel prepares to take possession of the Promised Land, they learn that this inheritance won’t really belong to them at all. The land remains the Lord’s property, and will revert every fifty years to the original division set up under Moses and Joshua.

The instructional session at Mount Sinai ends with a reminder about God’s ownership: “All tithes from the land, whether the seed from the ground or the fruit from the tree, are the Lord’s; they are holy to the Lord” (Lev 27:30). The tithe reminded the Israelites that the produce of the land and of the flock did not ultimately belong to them, but to God. It’s a reminder we need today as well—probably more than our ancestors did in ancient times!

Possessions may be a gift from God, but they can stand between us and God, and so Messiah’s invitation to follow him involves dispossession: “So therefore, any one of you who does not renounce all that he has cannot be my disciple” (Luke 14:33). And in case that’s not clear enough, Yeshua later adds, “No servant can serve two masters, for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and money” (Luke 16:13). For some characters in Luke’s Besorah, like the rich ruler in chapter 18, this means selling all they own, giving the proceeds to the poor, and literally following Yeshua. For others, like the wealthy tax collector Zacchaeus in Luke 19, it means practicing radical generosity and financial justice, even while (apparently) continuing his profession as a tax collector ( and see the similar picture in Luke 3:10–14). But in every case the goal is the joy of dispossession, getting free of our entangling stuff so that we can wholeheartedly serve and follow Messiah.

Let me suggest three specific ways of practicing the joy of dispossession today:

Report in to your owner every morning. Take a moment of quiet, solitude, and focus to check in with God, thank him that you and your time and energy belong to him, and genuinely make yourself available to him—and do it joyfully! (Of course, mornings are impossible for some folks, so pick another consistent time if you need to.)

Demonstrate daily that your possessions belong to God. Practice simple, on-the-ground generosity with your money and time. I learned long ago from my mentor Eliezer Urbach of blessed memory (although I’ve had to work at it ever since) to always have some cash on hand to help anyone in need that you might encounter. This practice still applies in today’s virtual economy.

Consume less. Simplify your possessions and spend minimal energy in accumulating more, to maintain your focus on serving Hashem, and to free up resources for others. To paraphrase Hillel, “the more stuff we possess, the more stuff possesses us,” and the stuff that possesses us may keep us from enjoying the simple obedience that Yeshua calls us to.

We get freed up as we realize that all we have in this world is on loan from God, the one who owns it all. When I forget this, it brings anxiety, greed, and distraction from what matters most. So it might be helpful to ask ourselves now and then, How have my possessions taken possession of me? Am I learning the joy of dispossession as I seek to follow Messiah?

All Scripture references are from the English Standard Version (ESV).

Sabbath Treasures in Heaven—God’s Treasure on Earth

The land is an important biblical character in its own right. The first portion (tithe) always belongs to the Lord, whether of produce or animals. In Parashat Behar, God commands Israel to give the land a holy Sabbath rest every seven years.

Parashat Behar, Leviticus 25:1–26:2; Haftarah: Jeremiah 32:6–27

Rachel Wolf, Congregation Beth Messiah, Cincinnati

And the Lord spoke to Moses on Mount Sinai, saying, “Speak to the children of Israel, and say to them: ‘When you come into the land which I give you, then the land shall keep a sabbath to the Lord.’”

This week’s parasha, Behar (on Mount Sinai), covers the laws of sabbatical rest for the land and people of Israel. The land comes into its proper purpose when the people of Israel are its custodians. The scripture is clear that the people do not own the land; Israel is merely its appointed steward and guardian.

The land shall not be sold permanently, for the land is Mine; for you are strangers and sojourners with Me. (25:23)

The Land Belongs to the Lord

The land is an important biblical character in its own right. As we have seen in previous readings, the first portion (tithe) always belongs to the Lord, whether of produce or animals. In Behar, God commands Israel to give the Land a holy Sabbath rest every seven years. After seven periods of seven years, the fiftieth year is to be a super-Sabbath in which everything is restored to its proper place and proper relationships.

You shall consecrate the fiftieth year, and proclaim liberty throughout all the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a Jubilee for you; and each of you shall return to his possession, and each of you shall return to his family. (25:10)

The land is to lie fallow for the fiftieth year. The people are to return, each, to their original land allocation from the Lord; and, if indentured servants, to return to their family.

The whole economy of Israel is based on the Jubilee year. There are many statutes in this portion about selling land ethically based on the number of years left until the Jubilee. This means that the economy is built on the idea that nobody actually owns his land. It is (in effect) a leasing system; when you buy land, you pay for years of use. The land belongs only to God. Yet, each tribe and family has a designated portion to inhabit and take care of.

Israel’s Time Also Belongs to the Lord

The people of Israel do not own their own time either! Their daily, weekly and yearly time belongs to the Lord, and he has commanded, above all, to keep the Sabbath a holy day unto God. In fact, the further we dig in, the more we begin to understand why the Shabbat is so important.

All of the various kinds of sabbaths link Israel’s holy purpose to the very beginning – to Creation. “Then God blessed the seventh day and sanctified it, because in it He rested from all His work which God had created and made” (Gen 2:3). The Sabbath is not only about physical rest. It is also about laying aside land rights, time, goods, and every other thing to the Lord, as a way of expressing trust in God and in the future that is in His hands. Let’s now take a look at the Haftarah portion.

Jeremiah 32 Helps Us Tie All of This Together

In Jeremiah 32:1-5 we learn that it is the 18th year of Babylon’s terrible siege of Jerusalem. Jeremiah is in King Zedekiah’s house prison because he has been prophesying that Judah will not succeed in overcoming the Chaldeans (Babylon). In this week’s haftarah portion (32:6-27), the word of the Lord comes to Jeremiah in prison, telling him to do something very specific and very odd. The Lord tells him that his cousin Hanamel is going to come to him and say, “Buy my field which is in Anatot [in Benjamin], for the right of redemption is yours to buy it.” (See Lev. 25:25-27 on the right of redemption.)

When this happens exactly as the word of the Lord said, Jeremiah knows he should buy the field. I am quoting this passage at length because it shows how serious this land transaction is, and to what lengths Jeremiah goes to make sure his deed is perfectly legal:

So I bought the field from Hanamel, the son of my uncle who was in Anatot, and weighed out to him the money—seventeen shekels of silver. And I signed the deed and sealed it, took witnesses, and weighed the money on the scales. So I took the purchase deed, both that which was sealed according to the law and custom, and that which was open; and I gave the purchase deed to Baruch the son of Neriah, son of Mahseiah, in the presence of Hanamel my uncle’s son, and in the presence of the witnesses who signed the purchase deed, before all the Jews who sat in the court of the prison.

Why did I say that this was a very odd thing for the Lord to ask Jeremiah to do? Because, Jeremiah clearly knew from the Lord, and had been prophesying for years, that the land he just purchased was shortly going to be captured by the Chaldeans, burnt and trampled upon mercilessly for seventy years. Jeremiah knew he would never live to live on his rightful inheritance.

So let’s look at what these Four Things have in common:

1. Shabbat

2. The Land of Israel

3. The People of Israel

4. Jeremiah’s Deed

Shabbat: All of the various Sabbaths—whether the weekly Shabbat or special festival Shabbats, or Yom Kippur—entail faithfully setting aside time to focus on the Lord our Creator.

The Land of Israel: This land is set apart or set aside for future purpose by God. It belongs to Him! Each piece of the land is allotted specifically, and one day its nature will be fully revealed and become God’s earthly Dwelling Place.

The People of Israel: The children of Jacob and their offspring are set apart or set aside for future purpose by God as a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Exod 19:6). “For the children of Israel are servants to Me; they are My servants whom I brought out of the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God” (Lev. 25:55).

Jeremiah’s Deed: Jeremiah is redeeming his hereditary land and setting it aside as a spiritual investment in the future of the land and the people of Israel. He was fully convinced Israel would again dwell in the land of their inheritance, even if he would not live to see their return. In modern idiom, God directed Jeremiah: “Put your money where your mouth is!” Jeremiah was happy to fully oblige!

Jeremiah’s purchase, completed in full public view, was an example to all the people of enduring faith in the promises of God! Here was this naysayer, the one constantly annoying and enraging the king, prophesying that the Jews will not be able to overcome Babylon! Yet, knowing his land will be invaded, captured, burnt, and trampled for seventy years, nevertheless, investing in the future of God’s land and people!

Treasures on Earth; Treasures in Heaven

Do not store up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moths and vermin destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where moths and vermin do not destroy, and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also. (Matt 6:19–21)

Jeremiah was storing up for himself treasures in heaven by investing in God’s treasure on earth! How can we, in our time, follow Jeremiah’s example by investing in God’s treasure on earth? If we look at the other three things on my list above, Shabbat, the land of Israel and the people of Israel, we can, together, prayerfully find ways to invest in those things God has set aside for His future plans, or that we are called to set aside for Him.

All Scripture references are from the New King James Version (NKJV).

Does God Need a Press Secretary?

It seems to me that God could use a good press secretary. You know, like C.J. on the classic TV show West Wing—the perfect prototype of the professional spin-doctors who protect and often augment the images of public figures.

Parashat Emor, Leviticus 21:1–24:23

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Congregation Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

It seems to me that God could use a good press secretary. You know, like C.J. on the classic TV show West Wing. Though she is a semi-fictional creation of Hollywood, C.J. is the perfect prototype of the professional spin-doctors who protect and often augment the images of public figures. And C.J. is the queen, a virtual Wonder Woman. Her impressive resume includes being able to drink whiskey like a sailor, banter like a roast master, and respectfully issue moral correctives to her superiors. Most importantly, though, she can really work a pressroom, answering all the questions that she wishes and skillfully deflecting those that would cause embarrassment to her boss, President Jeb Bartlett. And by the end of a press conference, it only seems reasonable for us to forgive the Prez for lying to the American public about his bout with MS, and forget that a ship full of US citizens is being held hostage in neutral waters. No matter what has occurred, when C.J. is done, the President’s reputation is left intact. After all, that’s what a press secretary is supposed to do, and that is precisely why it seems to me that God might need one—since, in the absence of one, pale imitators have assumed the role.

Of course, in reality God is above reproach and doesn't need any spin doctor. He has nothing to hide or explain away. But God does have multitudes of would-be press secretaries, people who presume to represent him, and his reputation in the world today suffers accordingly.

It is no wonder that Americans grow ever more cynical regarding organized religion. I think few people were totally surprised by the sexual abuses exposed in recent years within Catholic parishes, since the rumors have flown around for decades. But I do believe most people are appalled by the level of cover-up that appears to have occurred among those in high authority in the church, since their authority comes ostensibly from God.

But despite the recent falling from grace by Catholic clergy, we cannot place the entire responsibility of soiling the name of the Creator upon their collective backs. What of the moral indiscretions by the leadership of Liberty University, or some of the largest Evangelical megachurches? Haven’t they been lecturing us for ages about the higher morality God expects of us?

And even our own Jewish religious leaders have not been immune from various moral miscues, and rumors of abuse and misogyny continue to leak out of haredi communities. But lest the cynics and the skeptics have their way, let’s remember that for every religious leader that has been found morally wanting, there are many more who humbly serve God to the best of their ability. And ironically, the accusation of hypocrisy often leveled against the religious would not be possible unless it were already presupposed that they establish and live by higher standards.

This is the core value of today’s Torah portion and is the reason why Leviticus 22:32 has been called “Israel’s Bible in little.” It contains both the solemn warning against Chillul HaShem, profaning the Divine Name, and the positive injunction of Kiddush HaShem, the sanctification of God’s Name by each Jew with his life and if necessary, with his death. “You are not to profane my holy name; on the contrary, I am to be regarded as holy among the people of Israel; I am Adonai, who makes you holy” (CJB).

Throughout the history of our people Jewish martyrs have practiced Kiddush HaShem. Myriads of Jews walked to the gas chambers during the Shoah reciting the Shema, reminiscent of Rabbi Akiva’s heroic defiance of the Romans, blessing the Holy Name as he was flailed alive. And no greater act of Kiddush HaShem was performed than by the crucified Messiah who cried out in his final agony and resolution, “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

How sharp is the contrast between these selfless acts and the self-promoting claims of some religious hucksters who package God and sell his Holy Name like any other commodity. They call this marketing effort well-planned and efficient; I call it unethical and mercantile. But most of all I am appalled at the simplistic presentation of the divine mysteries, and the casual dismissal of the historic Jewish experience. A lifetime of experience reminds me that God’s highest values cannot be bartered through kitschy advertising slogans.

Irreconcilable is the distance between the greatest sacrificial act the world has ever known and the banality of some evangelistic programming. Lost in the world of religious ballyhoo are the words, “Be holy because I the Lord your God am holy” (Lev 19:2). These words, of course, appear in natural juxtaposition to the commandments that follow, therefore daring to suggest that more be expected from the fraternity of God than the mindless recitation of slogans and endless recruitment for the primary purpose of group affirmation and acceptance.

Would it then be advisable for the Messianic Jewish community to be silent, to withdraw into a collective shell of self-absorption? Some would argue that this is already happening, and, to a certain extent, I do not believe they are altogether incorrect. The question, though, is where we find the appropriate posture between timid introversion and adolescent vitriol. The answer, I would imagine, is not really one of posture but rather of attitude.

Do we imagine that we are somehow better than others with whom we share the local real estate? As we seek to understand our identities in Messiah, do we see ourselves gratefully disengaged from societal ills? Or are we willing to live in the creative tension as “new creations in Messiah,” and as human beings who share with all people a common experience in all of its joys, sorrows, pains, hopes, and delights? What particularly do we make of the Jewish people? If the Jewish people are truly our people and not merely an abstract theological construct, we should be able to affirm and appreciate the collective wisdom, worthy values, hopes, and aspirations of both the historical synagogue and the rest of the present-day Jewish community, despite our differences.

If we hold to the notion that God’s work of creation is magnificent, though tainted by the persistence of evil, life as we know it can still be deemed glorious. We should not sidestep our opportunity to bring hope into the world by demanding adherence to a few hackneyed presentations of doctrinal formulations. After all, Yeshua opposed every narrow-minded ideologue that placed their own particular understandings above the needs of those about them.

Since Yeshua commanded us to love our neighbor as ourselves, it is incumbent upon us to enter deeper relationships with others in our community, even if they are not in agreement with our particular doctrinal assertions. This is not to suggest that we in any way compromise our most highly valued principles, but rather that we practice these principles through normal engagement and consistent actions. By entering into a culture-engaging faith, we may affirm God’s creative power as expressed in such human endeavors as art, literature, drama, and music. We recognize intelligence as a God-given agency for the discernment and discovery of truth. If we are going to make a qualitative difference in the world about us, redemptive activity in the broader community is essential. Involvement in the spheres of medicine, the arts, politics, humanitarian endeavors, and all such society building efforts by extension would appear to be a divine mandate. Feeding the poor, reaching out to the helpless, the homeless, the emotionally needy and weary, stand tall amongst the prophetic pronouncements of the Scriptures.

Life everlasting rings hollow if it is merely an ephemeral concept divorced from life as we know it. But if Olam Haba (the Age to Come) informs Olam Hazeh (the Present Age), eternal life truly begins anew each day – and we become agents of God’s redemptive work, putting a heavenly spin on what might be construed as otherwise unpromising news from a world often mired in hopelessness.

Abraham Joshua Heschel would have made in my mind the most wonderful of Press Secretaries for the Holy One. His words, though right-sized and humble, should be an encouragement to us. “Great is the challenge that we face every moment, sublime the occasion, every occasion. Here we are contemporaries of God, some of His power at our disposal.”