commentarY

Abraham: Father of Faith of the Feet

Often we struggle to believe in our minds, which are subject to so many diverse influences. The key is to stop thinking that our faith should defy gravity! Try letting your faith slide down into your feet! Just start walking, one foot after the other, in the direction you best discern God’s leading.

Parashat Lech L’cha, Gen. 12:1–17:27

Rachel Wolf, Congregation Beth Messiah, Cincinnati

Lech L’cha means “Go! Leave!”

In Hebrew, when emphasis is desired, the same root word is stated twice in slightly different forms. God is presenting Abraham his mission, a mission with eternal consequences.

To paraphrase a popular TV show of the 60’s and 70’s that presented agents with wildly impossible missions, God (though he does not reveal all the details), essentially tells Abraham:

Good morning, Abram. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to go to the land I will show you. When you are 99 years old, you are to populate this land with a nation that will come from your body, in order that the world may come to know me and serve me in truth. Though the land’s true nature is hidden now, this is the Place where the heavens meet the earth, and from there all the earth will be healed. My eternal plan for the restoration of the world, worked out in human history, depends on you and your descendants.

Perhaps if Abraham had heard all of that he would have stayed in Haran!

Like the events of epic significance in each of the first two Torah portions, Lech L’cha, the calling of Abraham, is one of only a few major turning points in the Big Story of the Bible. This is essential to grasp, because how we understand the overall big story of the Bible (sometimes called a canonical narrative) will determine how we interpret all of the stories and details in the Bible. If we think of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and the people of Israel, as a background story to the main story told in the New Testament, our theology will be off-track. As one Christian ministry leader said to me: some Christian theologies seem to see the Jewish people as merely a delivery truck to bring Jesus to the Church.

There are two aspects of this epic portion I want to bring out.

In my reading this year of Lech L’cha, I was struck by just how many times God appears, or speaks directly, to Abraham! At every turn, at every juncture in the road, God is personally instructing Abraham on where to go and what he should do. Yes, Abraham takes a few detours along the way (Egypt, war with Kedorlaomer) but comes back to “Go” (Bethel) to seek the Lord’s direction. Even with the advantage of all this personal revelation, Abraham, like us, is still pretty clueless about the big picture. Nevertheless, he follows God’s instructions.

“Go to the land” is the calling and the goal, and remains so throughout the Torah. This second point intersects with the first. We see continued instructions about the land, and then, a little later, about a covenant of flesh for Abraham’s descendants. This covenant connects with the land of their inheritance.

Why would God appear to Abram/Abraham so many times unless God sees Abraham’s actions to be of primary importance in “His-Story”?

The eternal role of “The Land” to which Abraham is called cannot be overemphasized. It is not a passing phase of “covenant history,” but the heartbeat of God’s future blessing for humankind. Here are some examples of God’s personal instructions to Abraham. Notice how the land is the central part of the instructions:

Now the Lord said to Abram:

“Get out of your country,

From your family

And from your father’s house,

To a land that I will show you.” (12:1–3)

Then the Lord appeared to Abram and said, “To your descendants I will give this land.” (12:7)

And the Lord said to Abram . . . “Lift your eyes now and look from the place where you are—northward, southward, eastward, and westward; for all the land which you see I give to you and your descendants forever.” (13:14–18)

After these things the word of the Lord came to Abram in a vision, saying, “Do not be afraid, Abram. . . . Then He said to him, “I am the Lord, who brought you out of Ur of the Chaldeans, to give you this land to inherit it.” (15:1–9)

On the same day the Lord made a covenant with Abram, saying: . . . “To your descendants I have given this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the River Euphrates.” (15:17–21)

When Abram was ninety-nine years old, the Lord appeared to Abram and said to him . . . “I will establish My covenant between Me and you and your descendants after you in their generations, for an everlasting covenant, to be God to you and your descendants after you. Also I give to you and your descendants after you the land in which you are a stranger, all the land of Canaan, as an everlasting possession; and I will be their God.” (17:1–22)

Arise! Walk Through the Land: Faith of the Feet

Many theologians highlight 15:6, “Abraham believed in the LORD and rightness (tzedakah) was accounted to him” (my translation) as the epitome, the keystone, of Abraham’s faith, and, indeed, the decisive model for our own faith. They say that believing is what justifies us. While this is a potent and important verse, when taken out of context it distorts the powerful example of the faith of Abraham. Believing in the conceptual sense is only a part of faith. And many times, even weak mental faith can be shown to be strong when we act on it “by faith.”

Hebrews 11 makes it clear that faith in its mature outworking is faith of the feet. The men and women in the so-called “Hall of Faith” were not mystics with great conceptual belief in God. They were ordinary men and women who did their best to walk in obedience to what they understood God wanted them to do. Sometimes this involved great suffering. If we believe in our heart, it should come out in our feet.

Jacob (also called James) states this explicitly. In fact, he says (contrary to public opinion):

Was not Abraham our father justified by works [my emphasis] when he offered Isaac his son on the altar? Do you see that faith was working together with his works, and by works faith was made perfect [or complete]? And the Scripture was fulfilled which says, “Abraham believed God, and it was accounted to him for righteousness.” And he was called the friend of God. You see then that a man is justified by works, and not by faith only. (James 2:21–24)

Often we struggle to believe in our minds, which are subject to so many diverse influences. The key is to stop thinking that our faith should defy gravity! Try letting your faith slide down into your feet! Just start walking, one foot after the other, in the direction you best discern God’s leading. And, remember – being corrected here and there along the way is part of the journey! Your faith will be strengthened as you learn to practice foot-faith!

Scripture references are NKJV.

Lessons from Dry Ground

Parashat Noach seems increasingly sobering over the past few decades and especially this year. September and October seem to bring new catastrophic threats and concerns to the southeast portion of the USA and the Caribbean Islands.

Parashat Noach, Genesis 6:9–11:32

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Congregation Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

Parashat Noach seems increasingly sobering over the past few decades and especially this year. September and October seem to bring new catastrophic threats and concerns to the southeast portion of the USA and the Caribbean Islands. This year, as Hurricane Ian rapidly made landfall, my family like so many others held our collective breath.

The horror seemed so much more poignant since my wife and I have so many family members and friends on the west coast of Florida. Year after year they have confidently recounted to us how the brunt of the tropical storms missed them, and they did not need to evacuate. This year they did evacuate and thankfully they were safe! Others, though, were not so fortunate. In Lee County, Florida, which was hit the hardest, state and local warnings to evacuate were withheld until a day before the storm hit, way too late for so many. It is hard to know why, perhaps fear of error, concerns about panic, a misguided optimism that the storm might change path, or just a mistrust of the science that has become so accurate predicting these storms.

The biblical recounting of the great deluge records a century-long human avoidance of warnings. Of course, the Noah narrative speaks of a worldwide evil that is eradicated since humanity had become irreparably evil. So, I want to be cautious not to suggest that the proliferation of catastrophic natural disasters is that. But . . . these disasters may be due in part to humanity’s failure to keep covenant with God. In order to consider this we should look back briefly at last week’s portion, B’reisheet.

Before the Deluge

As described by the first two commands given in Genesis, humankind was given the responsibility of being the image bearers of God in this world in two distinct ways. First, humanity is commanded to have dominion in this world. “Be fertile and increase, fill the earth and master it; and rule the fish of the sea, the birds of the sky, and all the living things that creep on earth” (Gen 1:28). The second divine charge to humanity is to “care for (l’avdah, literally to serve or to worship) and guard the garden” (2:15). While this command is similar to the first command, it is actualized quite differently. In the first, humans mirror the image of God as kings, but in the second, as servants. Dominion or mastery does not suggest unbridled freedom to ravage, exploit, and exhaust the rest of the creation; rather as the only beings created in the image of God, humans are expected to be benevolent rulers, serving the creation as Hashem does.

The God of Israel is pictured as a uniquely benevolent ruler who cares for his creation. We are to do no less! It is the virtually unanimous conclusion among climate scientists that the tropical storms, floods, droughts, wildfires, and other natural disasters are the result of an irresponsible human footprint on the planet. Furthermore, that warning has been sounded for well over five decades and has increasingly been realized.

How we treat the planet is a direct reflection of our regard for others, for God, and for his creation. For Noach and family there were lessons to be learned on dry ground after the deluge. I would like to point to three of those and suggest how they might inform our going forward in a manner that I believe will be pleasing to the Creator and would allow us to be his image bearers as he created us to be.

Lesson 1: We can rise above our circumstances.

Midrash Tanhuma 5:4 asks, “What is meant by Noach was ‘righteous in his age’. It means that Noah was righteous in his age but not in others. To what may this be compared? If someone places a silver coin among copper the silver appears attractive.”

The same midrash gives an alternative understanding: “It can be compared to a jar of balsam placed at the top of a grave and gives off a goodly fragrance. Had it been placed in a home, how much more so?”

The midrash’s conflicting interpretations suggest that we are all products of our time, yet we can rise above the expectations of the age. We are not meant to be merely a reflection of current values but can be examples of a better way of living.

Lesson 2: The world was not created in a day, and neither will it be rebuilt in a day.

It took Noah 120 years to build the ark. The work before us will not be accomplished instantaneously. According to the midrashim it took so long so that men might have time to repent, even though in the end not one heart was turned.

Noach spelled backwards in Hebrew is chen, or favor. In Tractate Sanhedrin (108a) of the Babylonian Talmud we read this remarkable statement: “Noah had a death sentence sealed against him. But he found favor in the eyes of God.” In other words, but God chose to save him because of God’s own grace.

Slow and Steady, Board by Board, should be our motto.

Lesson 3: Our best will arise out of our diversity.

The rainbow is a symbol of God’s covenant with all living creatures (9:12–17). It represents all the color and contours of life. Sir Isaac Newton, who himself was a religious man and Hebraist as well as the father of modern science, observed that it is the entire range of the color spectrum that together comprises luminescence of pure light. The light of God is best seen in the diversity of humanity.

Later, God confounds language so that humankind might experience the command and blessing of filling all the earth. The diversity of languages, though sometimes a hindrance, might be understood as a blessed assistance, not a punitive measure as we often think of it.

We are made up of academics and those who work with their hands, those who think more transactionally and those who are more relational. Those who think in terms of larger, more systemic plans and those who tend to the immediate needs. We need each of these foci and therefore we can learn from each other.

After the Deluge

It is now 17 years since Hurricane Katrina made landfall. Four US presidents and eight congresses have since come and gone. In the immediate aftermath many stepped forward to help their neighbors, yet little has improved and every effort has been made by those who would shape the natural beauty of creation into vestiges of power to persuade us to keep the status quo. It is time to return to our heritage as the image bearers of the Creator and tend and protect his garden.

The Creation as a Pattern for Our Lives

The first book of the Bible, B’reisheet, lays a foundation for the rest of the Torah and the entire Bible. But beyond this literary function, we do well to recognize how this book lays a foundation for our lives as descendants of the first parents, as people born into and through families, as members of a holy people.

Parashat B’reisheet, Genesis 1:1–6:8

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann, Ahavat Zion Messianic Synagogue, Los Angeles

The first book of the Bible, B’reisheet (Genesis), lays a foundation for the rest of the Torah and the entire Bible. But beyond this literary function, we do well to recognize how this book lays a foundation for our lives as descendants of the first parents, not simply individuals, but as people born into and through families, as members of a holy people.

In all of these areas, we must not underestimate B’reisheet. It is profound, it is relevant, and it gives life to those who heed the lessons it provides.

This week’s parasha includes the first five chapters of B’reisheet and the first eight verses of chapter six, but let’s limit ourselves to examining the first two chapters and the lessons they teach us about how we might better make our way in the world. This emphasis surely reflects the intent of Moshe when he wrote Genesis, as he was teaching an entire people, accustomed only to slavery in Egypt, to inhabit a new identity and thus make their way in the world from being slaves in Egypt, through the wilderness, to fullness of freedom in the Land of Promise.

What lessons might we extract from these two chapters for our journey through life?

1. The beginning of chapter one pictures the situation God is addressing at the very beginning of things. “The earth was unformed and void, darkness was on the face of the deep.” God then begins making order out of chaos, separating light from darkness, waters from waters, with both the sky and the dry land appearing. What is the lesson for us?

For each of us, from childhood on, life challenges us to bring order out of chaos. This is a manifestation of our kinship with Adonai in whose image we are made. If we want to live a rewarding, productive life, we must accept that chaos is always pressing in on us. Our life will be freer and more rewarding to the degree that we do as Hashem did here, making order in the midst of chaos.

2. The account goes on to describe God making distinctions in the midst of creation, intending that various aspects of creation adhere to affinity with others of their own kind.

God said, “Let the earth put forth grass, seed-producing plants, and fruit trees, each yielding its own kind of seed-bearing fruit, on the earth”; and that is how it was. The earth brought forth grass, plants each yielding its own kind of seed, and trees each producing its own kind of seed-bearing fruit; and God saw that it was good.” (1:11–12 CJB)

And what does that mean for us? Just this: Much of God’s creative work involved making distinctions between this and that. We too, in our lives, must not consider all the “stuff,” the options, and the experiences of life to be an undifferentiated whole. Rather, we must learn to make distinctions, choosing this instead of that, wisely making evaluations that structure who we choose and allow ourselves to be. Making choices is inevitable, and not to choose is also to choose. As Torah will say later, “I have presented you with life and death, the blessing and the curse. Therefore, choose life, so that you will live, you and your descendants” (Deut 30:19 CJB). From beginning to end, Torah admonishes us to remember that choices are inevitable, and we must make good ones.

3. There is another lesson for us in that section of the text, and it is this: when facing disorder and chaos, we must not only introduce order and make distinctions involving choices; we must also accept that the stuff of life is not mechanical and predictable. Life includes unpredictability. Life is not restricted to mere robotic mechanical conformity. We must learn to accept life as a risky business, more than mere material things placed like ducks in a row. We must learn to tolerate unpredictability.

4. In this parasha we see that God created the earth and its inhabitants to be fruitful. We should order our lives so as to increase our productivity, usefulness, and satisfaction. We were created not simply to be, but to live fruitful lives, to fill the earth and subdue it. In Philippians 1:21–24, Paul tells the Philippians that he was anxious to depart from this life to go to be with the Messiah. He viewed this as the best of choices. Yet he decided that he would remain in this life, serving the Philippians among others, because that meant fruitful labor. Paul used the criterion of fruitfulness as a guide to his choices. As Torah teaches, and Paul confirms, so should we. We should always be asking ourselves, “What is the best thing for me to be doing now? And what am I doing so as to leave behind me the best that I am and the best that I know for the benefit of others?”

5. Notice that in the created order, man was not at first created to have dominion over other human beings. We were to have dominion over other aspects of the created order, but not over one another. The idea of dominion is intoxicating to people who are energized by being in control of all that happens around them, even control of other people and of social systems. We need to remember that Yeshua cautioned against this impulse: “You know that the rulers of the nations lord it over them, and their great ones play the tyrant over them. It shall not be this way among you. But whoever wants to be great among you shall be your servant, and whoever wants to be first among you shall be your slave” (Matt 20:25–27 TLV). Let us seek to be the servants of others, rather than their masters.

6. The meaning of Torah’s teaching that it is not good for man to be alone (Gen 2:18) is not exhausted by talking about marriage. A more foundational understanding that we must not ignore lies beneath this text. Even when Adam, the first man, was surrounded by a perfect creation, with meaningful work given to him by God himself, and even after Adam has been spoken of as being created in God’s image, the text insists that man was not complete without the companionship of someone else of his kind. Even the companionship of God himself could not meet this need. This is why, only upon seeing Chava, Adam says, “At last! This is bone from my bones and flesh from my flesh” (2:23).

The lesson for us is that the good life cannot be attained simply with beautiful things, and meaningful work, and even with intense religious experience knowing God himself. For life to be truly good we must cultivate relationships with other persons. Only then, can we say with Adam, “At last!”

7. Shabbat is the only day in which God did not create anything new, yet it remains for us a most life-giving day because balance and focusing on the Lord and our relationships is life-giving. We should not treat our lives like an assembly line. We were not created to be automaton drudges and production machines. We should not make ourselves nor let others make us into cogs in some wheel. As Paul the Apostle said, “You were bought at a price, so do not become slaves of other human beings” (1 Cor 7:23 CJB). By honoring and observing Shabbat we declare ourselves to no longer be slaves, but instead to being servants of God, who bids us to honor him in a balanced life.

Shabbat Shalom!

Simchat Torah: Beginning Again . . . Immediately!

As if to reinforce Rosh Hashanah as the beginning of our new year, Simchat Torah concludes our reading of the Torah (Deut 33–34) by immediately launching us into reading the Torah from the beginning again. So, we begin again immediately . . . not at some indistinct time in the future, but now.

Rabbi Dr. John Fischer, Congregation Ohr Chadash, Clearwater, FL

As a Jewish community we’ve just finished going through a time of introspection and a time of celebration. We moved through the awesome days from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur as we conducted an internal inventory of ourselves in the presence of the majestic King of the universe. Immediately afterward we’ve moved into a “season of rejoicing” through the week of Sukkot as we celebrate God’s provisions for our ancestors (Deut 29:5) as we walked with him through the wilderness journey he described as our honeymoon with him (Jer. 2:2). Now we come roaring into Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah, the conclusion of the festival cycle spelled out in Leviticus 23. As if to reinforce Rosh Hashanah as the beginning of our new year, Simchat Torah concludes our reading of the Torah (Deut 33–34) by immediately launching us into reading the Torah from the beginning (B’reisheet) again.

So, we begin again immediately . . . not at some indistinct time in the future, but now.

After Sukkot wraps up, Leviticus 23:36 instructs us to hold a special (“holy”) “eighth day” (shemini) commemoration of conclusion (atzeret) which then spills over into Simchat Torah. (Simchat Torah begins Monday night, October 17, or Sunday night, October 16, in Israel and Reform Jewish congregations.)

Taking a step back and looking at the bigger picture of Leviticus 23, it’s almost as if Shemini Atzeret concludes not only Sukkot, not only the fall holidays, but also the entire cycle of festivals described in Leviticus 23. (Remember the entire chapter is read as a unit.) Shemini Atzeret is designated simply as the “eighth day” after the end of Sukkot. And yet, since our calendar is built on the seven-day week based on the seven days of creation, the eighth day would itself signal a new beginning. Appropriately, Simchat Torah immediately picks up on this new-beginning theme by renewing our cycle of readings. Additionally, Simchat Torah in a sense serves as still another conclusion, this time to Shavuot; Shavuot is the holiday that celebrates the giving of the Torah while Simchat Torah celebrates our having the Torah.

A couple of weeks ago we approached and then observed Rosh Hashanah as an opportunity to begin a new year, to start afresh with our lives with God and with those around us. Now we can use our celebration of Simchat Torah to remind ourselves of our new intentions and new initiatives as well as to start afresh following God’s guidelines in the Torah. It’s yet another opportunity for a new beginning, for a fresh start for each of us.

In this fresh start, we should take to heart the concluding text of the Torah (Deut 34:10), which serves as part of the Simchat Torah readings. This parasha reminds us that “the Lord knew Moses face-to-face.” There was a close, intimate relationship between the two. Moses had come to know the character and person of the God of the universe. He knew him to be a God of surpassing compassion, overflowing love, superabundant kindness, and unrelenting forgiveness (Exod 34:6–7). Accordingly, we need to take the time to get to know the Lord more intimately and to model those same divine characteristics towards others. It’s part of our calling as a paradigm people (Deut 4:5–8; Exod 19:5–6). But the parasha also reminds us that the Lord knew Moses. That means Moses opened himself up to God; he didn’t hold anything back from God. We should follow this example as well.

The other part of the parasha for Simchat Torah, B’reisheet (Gen 1:1–2:3), reminds us that God walked with Adam and Eve in the garden in Eden. We, too, need to see this year as an opportunity to walk that closely with God, taking the time to get to know him better, and opening ourselves more fully to him. As we begin again immediately, this is something we can aim for and build on as we move forward through the coming year.

Simchat Torah can also serve as a time of forward vision for us as a Union. Although the pandemic adversely impacted and shaped much of this past couple of years, we were able to launch and build on some exciting fresh initiatives. These are opportunities that we can build on as we move through the coming year. Over 400 people attended our virtual Tikkun Leil Shavuot. Our new president, Rabbi Barney Kasdan, and our Education Chair Andrea Rubinstein (and team) further strengthened our Messianic Educator Certificate Program. It’s readily accessible for your synagogue teachers to take advantage of. We launched the Introduction to Lay Cantorial Training program under the capable leadership of Aaron Allsbrook. This is a wonderful opportunity to raise the level of cantorial work in your congregations and throughout the Union. We birthed Dorot, a task force which Deborah Pardo Kaplan effectively led. This task force researched and compiled ways we can all more effectively function in, and be relevant to, our emerging world and to our contemporary Jewish community. Their report is now available through the Union office, info@umjc.org. We’re launching Ashreinu School, an online Hebrew school to provide bar and bat mitzvah training for our kids. And of course, we have a new president, Rabbi Barney Kasdan, and a new secretary, Scott Moore, who’ll undoubtedly bring new ideas and effectively build on what we have accomplished. So, stay tuned for other fresh initiatives we as a Union develop this coming year. To learn more about any of these initiatives visit umjc.org.

In closing, as your outgoing president, I want to thank you again for giving me the opportunity to serve you these past four years. It has been a real privilege.

As we leave our sukkahs behind this Simchat Torah, let’s eagerly make the Torah more relevant in our lives and to those around us. And as we do so, we can more enthusiastically anticipate the time the Aleinu looks forward to, the time when the Living Torah will be among us again, and “the world will be perfected under the rule of the Lord Almighty.” Now is a great time to begin again!

Ha’azinu: Give Ear to the Future

Shabbat Shuvah has passed for this year. All Israel has listened to the final note of the shofar at the Neilah, the Closing of the Gates at the last Yom Kippur service. Life continues.

Parashat Ha’azinu, Deuteronomy 32:1–52

Rabbi Dr. Jeffrey Feinberg, Congregation Etz Chaim, Buffalo Grove, IL

During the Ten Days of Awe, Jewish people the world over brace for an annual ritual that requires exhaustive religious activity. A surprising number of Jewish families will attend seven religious services, three on the New Year, three on Yom Kippur, and the service on Shabbat Shuvah in between. They pray hundreds of prayers, sit through lengthy services, and finally fast and afflict their souls—all in a determined effort to “work out their salvation in fear and trembling.”

The most religious understand that the phrase “May you be written in the Book of Life” deals kindly with whether your death is decreed in the coming year. By Yom Kippur, “May you be sealed” conveys the hope that you will not die. Observant Christians often apply this same idea to living an eternal life in heaven, while observant Jews wish those living an additional year on earth. But remember that Jews understand that the covenant guarantees Jewish existence for a thousand generations. The Anointed One will come before then!

Shabbat Shuvah has passed for this year. All Israel has listened to the final note of the shofar at the Neilah, the Closing of the Gates at the last Yom Kippur service. Life continues.

For the first time since the days of Joshua, a majority of all Israel is returning to the Land! Is this a turning apart from repentance? Four generations ago, the Jewish people numbered 24,000 in the Land—about 0.3% of all Israel. The following generation experienced the Holocaust. A third of all Jewish people perished. Did this genocide spur Jewish repentance or a global taboo over future genocides against all humankind? Both? Neither??

Perhaps unnoticed by the eyes of the world, the Chief Rabbis of both the Ashkenazim and Sephardim did pray together in 1945 to publicly renew the covenant: as instructed by Torah itself, they read Deut 31:9–13 to all Jerusalem to teach the community and her children the fear of the Lord. And before the following Sabbatical year (1952), the state of Israel came to life! Torah has been read after every Sabbatical year in Jerusalem ever since, but who would know? Is Jerusalem with all Israel in a process of repenting her covenant infidelity as a people?

What if the next generation does not warrant Messiah? Suppose the time for repentance ends. What if no generation warrants Messiah? Will Messiah come anyway?

Deuteronomy 32 details God’s covenant relationship with all Israel. Ha’azinu (Give ear!) is a poem in the form of a covenant lawsuit. The song details the ways Israel would provoke a just and loving God to severely discipline them. What started as building a golden calf in the wilderness would blossom into a full-blown idolatry in the Land. The covenant lawsuit stands as a witness against Israel for choosing to build a golden calf, later to build more golden calves and high places to foreign deities, and still later, for practicing the idolatrous rituals of passing children through the fire to foreign deities.

Ha’azinu, God’s lawsuit, tells us today why we, our children, and majority Israel are born in exile, pouring out our libations to foreign idols, and failing to show covenant love for God alone:

Deuteronomy 32: Ha’azinu (“Give Ear”)

Verses 1–2 Exhortation to Israel with Heaven as Witness

3–4 The Praiseworthiness of God’s Character

5–6 The Lawsuit Complaint

7–14 Recollection: Israel’s Election and God’s Care for His People

15–18 The Indictment: All Israel’s Ingratitude and Apostasy

19–25 The Sentence: Covenant Curses, Measure for Measure

26–31 The Problem: Both Israel and Enemies Lack Insight

32–35 Double Problem: Israel’s Enemies Treat Israel with Cruelty

36 The Poet: Israel Made to Suffer More Than Double Punishment

37–38 The Taunt: God Taunts Israel for Pouring Out Libations to Foreign Deities

39 The Plea: God Alone Can Deliver Us

40–42 God’s Word: Oath to Deliver Israel

43 Call for All Creation—Including Israel among the Nations—to Worship God

44–47 Didactic Poem: Internalized as a Song for all Generations to Transmit

This reading year of 2022, Ha’azinu is chanted after Yom Kippur (which is not usually the case). The accompanying haftarah, Shirat David, the Song of David (2 Samuel 22:1–51), is chanted only on days after Yom Kippur. In this way, the nation enters the new season forgiven and sanctified. What comes next is Sukkot (Booths, the Feast of the Nations). All nations that will have gone up against Judah and Jerusalem are to bring gifts on this Feast for a thousand years (Zech 14:16–21; Isa 66:20–23; Rev 20:4–6).

Reading Shirat David recalls God’s oath to David, and David’s understanding of that oath. What is powerful about Shirat David is its invincible poetic structure as a victory song:

He is a tower of salvation to His king,

He shows loyal love to His anointed—

to David and to his seed, forever. (2 Sam 22:51)

Abarbanel tells us that David composed this song in his early years and kept it close by “reciting it on every occasion of personal salvation” (Stone Chumash, 1205). These times included life threatening situations when Saul hunted down David—God’s anointed—for a decade before the start of his public ministry as Israel’s seated king.

David had a clear understanding that God had given him an everlasting dynasty and that his seed would inherit the nations. Any nation choosing to make itself an enemy of David’s kingdom in effect curses itself to become Abraham’s and David’s inheritance. David concludes his song with words that Rabbi Saul of Tarsus cites over a thousand years later in Romans 15:9:

Therefore I praise You among the nations, Adonai,

and will sing praises to Your name. (2 Sam 22:50)

Paul knew about God’s oaths to Abraham and David, too. Why else would Paul characterize Israel as “enemies of the Gospel” and at the same time “beloved on account of the Patriarchs”? Why else would Paul cite the last line of Ha’azinu (Deut 32:43) right after citing David’s Song?

“For this reason I will give You praise among the Gentiles,

and I will sing to Your name.”And again it says,

“Rejoice, O Gentiles, with His people.” (Rom 15:9–10)

Paul clearly understood that the people of Israel would be singing God’s praises along with all nations, and with all creation, too!

What caused Israel to sing God’s praises in the past day of deliverance will surely cause Israel to again sing God’s praises in the day when “all Israel is saved” (Rom 11:26–28). Will all Israel be saved during Shabbat Shuvah or in the days following the final Day of Judgment?

Prayer for the salvation of all Israel is most powerful on this Sabbath day, when we read both Ha’azinu with its call for repentance and David’s triumphant song of victory after trusting God and spurning the idols of the nations. Why not call this Haftarat Yeshuah (Haftarah of Salvation)?

Should Messiah come this year, after Yom Kippur, when we read Ha’azinu and Shirat David, one can expect the whole nation to look on the one whom we all have pierced. Abraham and David will look on, Moses and the surviving nation will look on, and so will we. When the war to end all wars ends, Messiah will be coronated king over all the world. Ha’azinu is filled full in its meaning: Israel and the nations will be singing God’s praises, all creation will join in, and even the trees of the field will clap their hands.

All Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

Days of Awe and Reconciliation

During these Days of Awe, we have the opportunity to reach out to those we have offended, and even to those who have offended us, to offer an attitude of shalom that recognizes our differences while at the same time recognizing that spark of the Creator that is in each one of us.

Parashat Vayelech, Deuteronomy 31:1-30; Haftarah, Hosea 14:2-10 & Micah 7:18-20

Michael Hillel, Chavurah Adonai Shammah, Netanya, Israel

By the time you read (or listen) to this commentary, we will be in the Days of Awe, or in Hebrew, Yamim Noraim, a time that is also known as the Days of Repentance. These days are set aside for serious introspection, a time to consider the previous year’s mistakes and shortcomings, and to repent before the sound of the shofar that ends Yom Kippur.

While much of the focus is on one’s mistakes in keeping or not keeping the commandments of God, there is an equally important focus on seeking reconciliation with others that one may have wronged in word or deed during the past year. In Mishnah Yoma 8:9 it is written

For transgressions between a person and God, Yom Kippur atones; however, for transgressions between a person and another, Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases the other person.

This need to be reconciled before bringing one’s offering before Hashem is not only an idea developed by the sages. Yeshua taught his talmidim:

Therefore, if you are presenting your offering upon the altar, and there remember that your brother has something against you, leave your offering there before the altar and go. First, be reconciled to your brother, and then come and present your offering. (Matthew 5:23–24)

In our world today, which is fractured and polarized over an unending multitude of ideologies and opinions, it is safe to say that regardless of our stance on such issues, we have offended and even isolated ourselves from others to whom we were once close. During these Days of Awe, we have the opportunity to reach out to those we have offended, and even to those who have offended us. This reaching out is not an opportunity to correct or change the other’s mind. Rather, it is an opportunity to offer an attitude of shalom, one that recognizes our differences while at the same time recognizing that spark of the Creator that is in each one of us, that which makes us family.

The psalmist wrote, “Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brothers to dwell together in unity” (Psa 133:1), and Yeshua taught his disciples, “By this, all will know that you are My disciples if you have love for one another” (John 13:35). Note that neither the psalmist nor Yeshua called for complete agreement between one another, rather that we are to love and respect one another even though we are different.

As well as being in the Days of Awe, the Shabbat between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur is called Shabbat Shuvah, “Shabbat of Return.” This Shabbat draws its name from the first of its two haftarah readings, which opens with, “Return O Israel, to Adonai your God, for you have stumbled in your iniquity” (Hos 14:2). The second haftarah reading begins with these words of encouragement if Israel does return, “Who is a God like You pardoning iniquity, overlooking transgression, for the remnant of His heritage? He will not retain His anger forever because He delights in mercy” (Mic 7:18). We often hear these two verses, assuming that they refer to our relationship with Hashem, broken by our transgressions and restored by our repentance. But remember, our relationship with Hashem is affected by our relationship with others.

In looking at the idea of repentance and restoration during the Days of Awe, I came across an article by Chosen People Ministries in which the author makes an incisive observation.

Most Jewish people understand that repentance is the path that leads to salvation and the forgiveness of sin, which is secured at the closing moments of Yom Kippur. Though it is difficult to explain the difference between the Jewish and Christian understanding of salvation, the Jewish community stresses forgiveness far more than personal salvation, especially as salvation is understood by most Christians. Jewish people are not as apt to think about personal salvation or a secured future beyond the grave in the same way Christians do. (https://www.chosenpeople.com/what-are-the-ten-days-of-awe/)

When I read this, I immediately thought of the seventh bracha in the Daily Amida:

Heal us, Lord, and we shall be healed. Save us and we shall be saved, for You are our praise. Bring complete recovery for all our ailments for You, God, King, are a faithful compassionate Healer. Blessed are You, Lord, Healer of the sick of His people Israel. (Koren Siddur)

Israel has always seen Hashem as the one who took care of them in a very practical manner. Remember Hashem’s words to Israel as they prepared to enter the land of Canaan: “I led you forty years in the wilderness—your clothes have not worn out on you, and your sandals have not worn out on your feet” (Deut 29:4). Equally Hashem provided food and water for the people and the animals throughout their travels. One of the most moving prayers of the Rosh Hashanah service, Unetanah Tokef, reveals this understanding of the care of Hashem for his people.

On Rosh Hashanah, it is inscribed, and on Yom Kippur, it is sealed—how many shall pass away and how many shall be born, who shall live and who shall die, who in good time, and who by an untimely death, who by water and who by fire, who by sword and who by wild beast, who by famine and who by thirst, who by earthquake and who by plague, who by strangulation and who by lapidation, who shall have rest and who wander, who shall be at peace and who pursued, who shall be serene and who tormented, who shall become impoverished and who wealthy, who shall be debased, and who exalted. But repentance, prayer and righteousness avert the severity of the decree. (sefaria.org.il/)

It is often said that followers of Yeshua are so concerned with their eternal dwelling that they care little for their earthly one. Maybe what is necessary is a blend of the two understandings, recognizing that Hashem cares both for our here-and-now and for our eternity. During these Days of Awe, we should look for ways to be reconciled with those whom we’ve drifted away from. Equally, we should remind ourselves that Hashem is not only concerned with our eternal dwelling place but with each and every day of our lives on this plane as well.

Shabbat shalom and gemar chatimah tovah!

All Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

Crossing Over into Our Covenant

In Moses’ final discourses, he makes it clear that entering the land God has chosen, by crossing over from Moab, is equated with entering into our covenant with God. We can’t fully grasp our purpose as a people unless we understand the decisive connection between God, the people of Israel and the Land of Israel.

Parashat Nitzavim, Deuteronomy 29:9–30:20; Haftarah, Isaiah 61:10–63:9

Rachel Wolf, Beth Messiah, Cincinnati

In Moses’ final discourses, he makes it clear that entering the land God has chosen, by crossing over from Moab, is equated with entering into our covenant with God. We can’t fully grasp our pivotal purpose as a people unless we understand the irreducible, decisive connection between God, the people of Israel and the Land of Israel and the import of these three for God’s ultimate plan for humanity! After all, God has called this chosen clan Hebrews (עברים—those who cross over).

In Ki Tavo, after reciting the blessings and curses related to living on the land, Moses says this:

These are the words of the covenant [Hashem made with Israel] in the land of Moab, besides the covenant which He made with them in Horeb. (Deut 29:1)

As we read Moses’ discourse on the plains of Moab, we are struck by how it prophetically portrays the whole sweep of Jewish redemptive history! Can you feel the drama?

You stand (nitzavim) today, all of you, before Hashem your God . . . that you may cross over into the covenant of Hashem your God, and into his oath that he cuts with you today. (Deut 29:1 my translation)

Wait! Didn’t we enter into covenant at Sinai??

Well, the scriptures seem to indicate that key covenants can take many stages to be fully realized. Let’s look at Abraham as an example: God calls Avram to the land in Genesis 12 saying, “I will bless you and make your name great . . . in you all the families of the earth will be blessed.” God then makes a formal covenant with Avram in Genesis 15, one Avram is to “know certainly” (15:13). And then, because of Abraham’s obedience, God says:

By Myself I have sworn, says Hashem, because you have done this thing, and have not withheld your son, your only son—blessing I will bless you, and multiplying I will multiply your descendants. . . . . In your seed all the nations of the earth shall be blessed, because you have obeyed My voice. (Gen 22:16–18)

Yet, even after three stages, God’s history-changing land covenant with Abraham is far from its completion. Abraham’s seed through Jacob had yet to experience many subsequent stages of this covenant, including Sinai. Here in Nitzavim, Abraham’s descendants are about to embark on a new and crucial stage of this covenant.

Entering the land is the way that the people of Israel are now to further the progress of God’s covenant with Abraham (Deut 29:12–13). As Moses ponders the gravity of the covenant and its promises, his discourse reflects a far-reaching prophetic view of Jewish history. He sees that this people he has shepherded will not be faithful, yet God’s mercy will prevail. Still, at this juncture, the people have an opportunity to walk in God’s ways: “See I have set before you today life and good, death and evil. . . . Choose life that both you and your descendants may live” (30:15–20).

Here are some of the stages Moses foresees along the rocky path of the fulfillment of Abraham’s covenant. Much of this language is echoed in Ezekiel 36.

When Israel is expelled from the Land, God’s Name is profaned

When Israel sins by following other gods, the land suffers desolation and loses its fruitfulness. When Israel is expelled from the Land, God’s Name is profaned by the very fact that his people are exiled from his/their Land. In this week’s portion this is stated in a warning from Moses that saw its fruition in the time of Ezekiel (Deut 29:20–29; Ezek 36:19–20).

Likewise, bringing Israel back to the Land is how God sanctifies his Name.

And I will sanctify My great name, which has been profaned among the nations . . . and the nations shall know that I am the Lord . . . when I am hallowed in you before their eyes. For I will take you from among the nations, gather you out of all countries, and bring you into your own land. (Ezek. 36:23–24; cf. Deut 30:1–6)

After the curses take effect, God takes it upon himself to bring lasting blessing.

Moses seems aware that the curses, the natural effect of the people’s straying, are inevitable. However, after “all these things come upon you,” God is eagerly waiting for the opportunity to heal and bless.

And the Lord your God will circumcise your heart and the heart of your descendants, to love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul, that you may live. (Deut 30:6)

For I will . . . bring you into your own land. Then I will sprinkle clean water on you, and you shall be clean. . . . I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you. . . . I will put My Spirit within you and cause you to walk in My statutes. . . . Then you shall dwell in the land that I gave to your fathers; you shall be My people, and I will be your God. (Ezek 36:24–28)

The curses return upon those who curse Israel.

When Israel is disobedient, God uses the nations to bring the curses upon Israel. But when Israel, God, and the Land come together the curses fall back on those who have cursed Israel (Deut 30:7–10).

The last Haftarah of Consolation, Isaiah 61:10–63:9, speaks of our hope: the fulfillment of the blessing of Abraham. It opens with “I will greatly rejoice in the Lord.” This rejoicing is not ephemeral; it is for the time when God finally makes all things right. Here we see God’s “own arm” bringing salvation (Isa 63:2–6). Yet, in context, this is not the salvation of atonement, it is the salvation of judgment: God himself finally judges the nations that refuse to bow to God’s authority; in this God finally overcomes evil and sorrow.

The birth of Isaac is connected to our ultimate hope.

With great insight our sages in Pesikta deRav Kahana 22 understood that Isaiah’s “great rejoicing” here is connected to the birth of Isaac, the heir of Abraham’s covenant. They understood Sarah’s rejoicing at Isaac’s miraculous birth as both causing and foreseeing the worldwide jubilee that God will bring about at the end. After giving birth to Isaac, Sarah exclaims: “God has made me laugh, and all who hear will laugh with me” (Gen 21:6). The sages discuss the meaning of Sarah’s laughter. In short, Sarah’s joy brings the full covenantal blessing to the world: the blind see, the deaf hear, the insane become sane, and all the babies of the princesses of the world nurse at Sarah’s breast!

This is a profound insight into the far-reaching effects of God’s humble plan to create a priestly nation through the barren couple Abraham and Sarah. We may well meditate on why God, Creator of all, determined that the remedy of the afflictions of the world would depend on something as mortal and undependable as the descendants of Jacob. Yet, it is in this very human, yet supernatural, ongoing covenantal history of our people that we find our hope.

Hebrews 6 also cites God’s land covenant with Abraham as the source of our hope:

Now when God made his promise to Abraham, since he could swear by no one greater, he swore by himself, saying, “Surely I will bless you greatly and multiply your descendants abundantly” [Gen 22]. . . . [T]he oath serves as a confirmation to end all dispute. In the same way, God wanted to demonstrate . . . that his purpose was unchangeable. (13–17 NET)

Through Yeshua, we, with renewed hope, can reenact the drama of Nitzavim. We, with our people, all of us together, are poised, standing before the Lord, in sight of the land of our inheritance. Our people in Moses’ time were not prepared to walk in the ways of Hashem. But through Yeshua’s work on our behalf, we are made ready to inherit the land. And we are called, in Yeshua, to also sanctify our brethren for this, our inherited national calling to ultimate hope.

Unless otherwise noted, Scripture references are from the New King James Version (NKJV).

Distraction-Fasting, Monotasking & Hesed-Casting

As a well-worn saying goes, it’s the preacher’s job to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. They’re both challenging tasks, which is why Jewish tradition devotes, not just a day or two, but a whole season to affliction and comfort.

Selichot 5782, Exodus 34:6–7

Rabbi Russ Resnik

As a well-worn saying goes, it’s the preacher’s job to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. They’re both challenging tasks, which is why Jewish tradition devotes, not just a day or two, but a whole season to affliction and comfort. For three weeks leading up to Tisha B’Av we read the Haftarot of Affliction, and for seven weeks afterwards the Haftarot of Comfort.

And if we pay attention to our readings and to the whole drama of this season, we might not be entirely comfortable as we approach the holy Yom Ha-Din, the Day of Judgment, or Rosh Hashanah. Accordingly, Jewish custom provides a final service of forgiveness or Selichot, starting on the Saturday night before Rosh Hashana, or if there are fewer than four days between Saturday and Rosh Hashana, on the previous Saturday night, as it is this year.

You can find Selichot prayers in a special prayer book or online, or you can read psalms of supplication like Psalms 32 and 51. The most important text for Selichot, though, is the Thirteen Attributes of Mercy from Exodus 34:6–7. Moses is speaking with Hashem after the incident of the golden calf. In response to Moses’ pleas, Hashem has agreed to show mercy to Israel and remain among them by his presence. Then Moses asks God to show him his glory and Hashem agrees—but it’s not a visual revelation that he gives. Instead, the Lord describes himself to Moses:

Adonai, Adonai, God, merciful and compassionate, slow to anger, rich in grace and truth; showing grace to the thousandth generation, forgiving offenses, crimes and sins; yet not exonerating the guilty . . .

In this ultimate moment of divine self-revelation, God’s “glory” is not a visual display, but a verbal declaration of mercy and compassion. Our sages discern Thirteen Attributes of Mercy that are especially comforting as we seek forgiveness at this time of year. The final four attributes all have to do with God’s forgiveness:

10. Forgiving offenses (nosei avon)—Avon refers to intentional sin, which God forgives if the sinner turns back to him.

11. Crimes (pesha)—Pesha is sin with malicious intent, rebellion against God. God allows teshuva, turning back, leading to forgiveness even for this.

12. And sins (v’hata’ah)—And God forgives sins committed out of carelessness, thoughtlessness, or apathy.

13. Exonerating (v’nakeh)—The actual text here says God does not exonerate the guilty, but this implies that he does exonerate those who truly turn back to him.

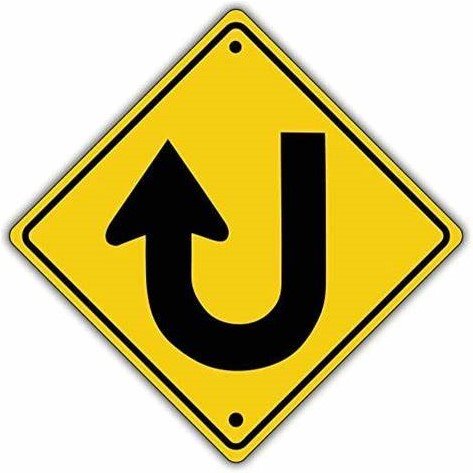

These final attributes call for teshuva, a U-turn from our own ways and back to God. But something within our human nature resists the sort of change that teshuva entails. We love routine and the status quo—especially when it comes to inward things. We might like to try out new experiences, new flavors and colors and places, but when it comes to changing the things closest to ourselves, we’re most likely to resist. Just ask anyone—including yourself—who’s tried to exercise more or eat less or phase out some unhealthy habit. We resist change.

As a rabbi I’ve noticed this sort of resistance when we talk about teshuva during this season, as we inevitably do. I can even imagine some of my readers groaning as I bring up that term. But please remember my job description: To comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Yes, we emphasize teshuva during this whole season, because genuine comfort only comes after affliction.

Our tradition provides lengthy prayers of remorse and confession through the Days of Awe, and we might need to overcome inner resistance to really put our hearts into this practice. But as we do, we begin to see ourselves and our lives in light of God’s merciful presence. We might end up like Moses, who “bowed his head down to the earth and worshiped” after hearing the Thirteen Attributes (Exod 34:8), seeing not only who God was, but who he himself was too.

But we’re unlikely to respond like Moses amid our entertainment, distraction, and info-glutted lives, so let’s prepare ourselves during this season with practices like these:

Distraction-fasting. Distraction, entertainment, and information inflation characterize the day in which we live. Let’s turn something off from now through the Days of Awe. I think I’ll put a pause on my recently acquired Spelling Bee habit (it’s a New York Times vocabulary game—but I can live without it). We’re approaching the Days of Awe, so let’s simplify our mental-emotional surroundings and make room for awe.

Monotasking. We all know that you can’t really multitask, as in doing two or three things at the same time, but we keep trying. Let’s refrain for a while and instead give full attention to one thing at a time, hour by hour and day by day. Practice the kind of focus that will be required of us when we actually get into the prayers for Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur.

Hesed-casting. Hesed, as undeserved kindness or generosity, is a leading quality among the Thirteen Attributes, and we can reflect God’s self-description with small, barely noticeable acts of hesed. Give someone close to you a genuine, but unexpected, word of affirmation or encouragement. Decide not to criticize or minimize the efforts of someone else, even if you think they deserve it. Give relational freebies—and enjoy doing it!

In the prologue of his Besorah (Gospel), John highlights the paired attributes of hesed v’emet listed in Exodus 34: “The Torah was given through Moses; grace and truth came through Yeshua the Messiah” (1:17). Commentators often see this verse as a contrast between Moses and Yeshua, between law and grace. But it’s more accurate to think of it as fulfillment. Moses gave us Torah, which speaks of grace and truth. Yeshua the Messiah embodies the very same grace and truth, living them out among us and through us.

We’ll repeat the Thirteen Attributes in our prayers from the night of Selichot through Yom Kippur. They provide the essential backdrop for all our confessions of sin. Without the declaration of God’s mercy, however, we’d turn the liturgies of confession into a dreary, self-absorbed, and depressing mess. With it, confession leads to a deep encounter with the God of grace and truth, embodied in Messiah Yeshua—an encounter with the potential to change us from within.

Building the World with Love, One Nest at a Time

The commandments are for our benefit; in a sense, they are one aspect of God’s ḥesed toward us. The sages of the Talmud contend that this is a model for us: we imitate God by showing ḥesed to those around us, and even to the natural world.

Parashat Ki Tetse, Deuteronomy 21:10–25:19

Dave Nichol, Ruach Israel, Needham, MA

In parashat Ki Tetse, we find a list of seemingly random commandments, including this one:

If there happens to be a bird’s nest in front of you along the road, in any tree or on the ground, with young ones or eggs and the hen sitting on the young or on the eggs, you are not to take the hen with the young. You must certainly let the hen go, but the young you may take for yourself so that it may go well with you and you may prolong your days. (Deut 22:6–7)

I, for one, have never had this happen to me. Even so, I can’t help but ask, why? Ramban (Moshe ben Nachman, 13th century) uses his comments on this verse to ask the question, what is the purpose of the commandments?

In this case, Ramban declares that the commandment is not intended for God’s benefit, finding it presumptuous to claim that God needs anything. Nor is it for the benefit of the mother bird; after all, the Torah certainly allows slaughtering animals for food. Rather, the purpose of this commandment is to prevent us from acting cruelly. This mitzvah (commandment) teaches us that even this (destructive but permitted) act of taking young birds for our nourishment must be mitigated, if only a little, by compassion.

So, what is the purpose of the commandments? They are first and foremost to benefit us. In the case of this mitzvah, the primary benefit is teaching us the importance of compassion.

In the Talmud, Rabbi Hama explores the verse “You shall follow after the Lord your God…” (Deut 13:5), asking the question: is it really possible to “follow after” the Divine Presence? Put differently, how do we, mere humans, imitate God, who is so profoundly other? He answers his own question: “Rather, the meaning is that one should follow the attributes of the Holy One, Blessed be He.” He provides several examples:

Just as He clothes the naked, as it is written: “And the Lord God made for Adam and for his wife garments of skin, and clothed them” (Genesis 3:21), so too, should you clothe the naked. Just as the Holy One, Blessed be He, visits the sick, as it is written with regard to God’s appearing to Abraham following his circumcision: “And the Lord appeared unto him by the terebinths of Mamre” (Genesis 18:1), so too, should you visit the sick. Just as the Holy One, Blessed be He, consoles mourners, as it is written: “And it came to pass after the death of Abraham, that God blessed Isaac his son” (Genesis 25:11), so too, should you console mourners. Just as the Holy One, Blessed be He, buried the dead, as it is written: “And he was buried in the valley in the land of Moab” (Deuteronomy 34:6), so too, should you bury the dead. (Sotah 14a).

These actions attributed to God strongly echo those listed by Yeshua as characteristic of those who would enter his kingdom:

Then the King will say to those on His right, “Come, you who are blessed by My Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave Me something to eat; I was thirsty and you gave Me something to drink; I was a stranger and you invited Me in; I was naked and you clothed Me; I was sick and you visited Me; I was in prison and you came to Me.” (Matt 25:34–36)

These examples—clothing the naked, visiting the sick, comforting mourners, visiting prisoners—can be summed up in the concept of gemilut ḥasadim, or “works of ḥesed.”

While ḥesed can be translated as simply “love,” it is often translated as “lovingkindness.” Alan Morinis, in his excellent book Everyday Holiness: The Jewish Spiritual Path of Mussar, defines it as “generous sustaining benevolence.” From the thirteen attributes that we recite (especially during High Holidays), we learn that ḥesed is a fundamental attribute of God.

But ḥesed is not just any old attribute of God. Some streams of our tradition see it as an essential part of the fabric of creation. Some read olam ḥesed yibaneh (Psalm 89:3, rendered by the TLV as “Let your lovingkindness be built up forever!”) as “the world was built with ḥesed.” Pirkei Avot states that “the world stands on three things: Torah, worship, and acts of ḥesed” (1:2).

R. Chaim Friedlander, a 20th century mussar teacher, taught that Noah’s ark was not a place simply to wait out the flood, but was a training ground for ḥesed (Siftei Hayyim, “Olam Ḥesed Yibaneh”). Noah and his sons and daughters had to work all day with minimal rest to care for the animals. What’s more, they had to approach each animal according to its own needs and requirements—as an individual. In this way, the ark was a “school of ḥesed”—a perfect antidote to the violence that characterized humanity before the flood. According to this reading, the ark was not to save Noah’s family from the water, as much as to get humanity back on track morally.

Ramban concludes that the commandments are for our benefit; in a sense, they are one aspect of God’s ḥesed toward us. The sages of the Talmud contend that this is a model for us: we imitate God by showing ḥesed to those around us, and even to the natural world.

There’s a meaningful relationship between “the purpose of the commandments” and “the purpose of our lives.” We can conceive of creation as a flow of ḥesed from God into the created order, where our job is to keep it flowing by giving to others from what we have been given (I owe this particular imagery to R. Shai Held of Yeshivat Hadar). Neglecting to do ḥesed creates a blockage in this flow from God that sustains the world.

Does this mean that our purpose in this life is primarily doing good for others? Should we understand ourselves first and foremost as ḥesed-distributors? Well—spoiler alert—I think it is! “He has told you, humanity, what is good, and what Adonai is seeking from you. Only to practice justice, to love mercy [ḥesed], and to walk humbly with your God” (Micah 6:8).

Living in a continual posture of ḥesed is not natural to us. It is radically against the grain to give when we are inclined to self-preservation, to let go of our own priorities—even the noble, important ones—and truly see another person and their needs; to live a life of freely giving. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you? Love your neighbor as yourself? Habituating ourselves toward ḥesed is where the rubber meets the road.

That’s not to say we should become versions of Doug Forcett, the character in the TV show The Good Place who feels obligated to be generous ad absurdum, letting people walk all over him out of a commitment to a twisted, extreme form of ethics. In the language of the kabbalists, even though the world may be founded on ḥesed, it is balanced with gevurah, strength or boundaries.

That said, it would be a mistake to contextualize away this commandment to do ḥesed. The teaching of these sages, along with our master Yeshua himself, challenges us to make ḥesed the organizing principle of our lives—even to an extent that would be seen as truly radical in contemporary society.

Recall that Yeshua extends ḥesed even to life itself: “This is My commandment, that you love one another just as I have loved you. No one has greater love than this: that he lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:12–13).

In the end Ramban finds that the commandments are for our benefit, even (especially?) those that require some self-sacrifice. To truly live our lives this way requires a tremendous amount of faith that God’s ḥesed will continue to flow to us. Perhaps when we find it difficult it will help us to remember the words from our parasha: that even taking a posture of ḥesed in routine acts (you know, like taking baby birds from a nest for lunch) will bring about “that it may go well with you and you may prolong your days.”

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

Creating a Favoritism-Free Zone

I long for the day when “Messianic Jewish” is not a religious brand, but a description of the values of our community, values that reflect the presence of Messiah among us. This week’s parasha opens with a foundational text for creating this sort of community.

Photo: https://raghuraifoundation.org/india-bw/

Parashat Shoftim, Deuteronomy 16:18–21:9

Rabbi Russ Resnik

I long for the day when “Messianic Jewish” is not a religious brand, but a description of the values of our community, values that reflect the presence of Messiah among us. In the UMJC we seek to embody something like this in the core values articulated by our delegates years ago: “Deference and respect are key elements in our fellowship” (Core Value 1); “We recognize that all people are made in the image of God and therefore will endeavor to treat them with respect” (Core Value 5).

This week’s parasha opens with a foundational text for creating this sort of community:

Judges and officers you shall appoint in all your towns that Hashem your God is giving you, according to your tribes. They shall judge the people with righteous judgment. You shall not distort justice; you must not show favoritism, and you shall not accept a bribe, for a bribe blinds the eyes of the wise and subverts the cause of the righteous. (Deut 16:18–19, author’s translation)

The Torah says that the judges, or Shoftim as in the title of our parasha, shall judge the people with righteous judgment (mishpat tzedek). But isn’t this phrase redundant? Is not judgment (mishpat) righteous (tzedek) by definition?

The classic commentator Sforno interprets this two-part phrase to mean that the judge “must not be lenient with one and harsh toward the other,” reflecting the next verse, “You shall not distort justice; you must not show favoritism.” If we’re honest with ourselves, we’ll recognize that we all tend to favor the attractive, the loveable, and the cooperative among us over the dumpy, grumpy, and difficult. And even if we’re honest enough to recognize this bias in ourselves, we still must work hard to overcome it, because this tendency, however natural and widespread, distorts justice.

Ya’akov applies the issue of favoritism to real life in our congregations.

My brothers and sisters, do you with your acts of favoritism really believe in our glorious Lord Yeshua the Messiah? For if a man wearing a gold watch and an expensive suit comes into your synagogue, and a homeless guy in second-hand clothes comes in right after him, and you show respect to the man in the suit and say, “Please, sir, sit here in a good spot,” and you ignore the poor man or say, “Here’s a nice seat in the back row,” are you not showing favoritism and proving to be judges with bad hearts? (Jas 2:1–4, paraphrased)

Let’s remember that Moses gave this instruction about avoiding favoritism to a totally low-status group, a people recently delivered from the degradations of slavery. Likewise, Ya’akov exhorts a community that is inhabiting the margins for the sake of Messiah Yeshua, oppressed by the powerful. Ironically, such groups are still tempted by outward show and pretense. Apparently, although we should know better, we have a blind spot regarding favoritism. Every group, most emphatically including religious groups, tends to create hierarchies, in-groups and out-groups, and outward emblems of power and acceptability—which is one reason for the negative image of religion in general today.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt notes in his landmark 2012 publication, The Righteous Mind, that all human cultures develop—and are developed by—religious practice. And most religions entail what Haidt calls “parochial altruism,” that is, benevolence toward one’s fellow community members, even if it costs. This sort of altruism, even though it remains in-house, doesn’t normally increase animosity toward outsiders. For this reason, Haidt, a secular Jewish scholar, goes against the grain of today’s culture to portray religion as a positive force in the evolution (his term) of the human race. The Torah entails parochial altruism for sure (“love your neighbor as yourself”), but points beyond to a wider altruism (“love the stranger.”) Messiah Yeshua carries this to its logical fulfilment: “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven” (Matt 5:44–45). This is the unique perspective of the religion of Israel and its Messiah.

Favoritism undermines this expansive ideal of altruism, as our Torah portion notes. We become parochial, or even more narrow in focus, when we decide by appearances instead of by mishpat.

Many years ago, a prominent, but shabbily dressed Polish rabbi was taking a train to visit another city. A well-dressed young Jewish man in the same car treated him rather rudely on the journey, and then was mortified when they both got off the train and the unrecognized rabbi was greeted by throngs of his admirers. When the young man saw this, he apologized for his earlier behavior, and the rabbi said: “I wish that I could accept your apology, but I cannot. You are apologizing to me, a respected rabbi, but it was some unknown old Jew that you insulted.” In other words, the chastened young man was still a respecter of persons, still showing favor based on outward appearances. Such favoritism prevails everywhere, but we have the opportunity to create communities where it does not prevail.

The synagogue, according to Yaakov, should be the one place where no one has to compete for attention, status, or affirmation, but where we grant these freely to all. Synagogue is, or should be, the place where the values of appearance and power, so dominant in our culture today, are overturned. Yaakov pictures this outlook as essential to real faith: “My brothers and sisters, do not hold the faith of our glorious Lord Yeshua the Messiah while showing favoritism” (James 2:1 TLV).

Now is a good time, early in the month of Elul, to examine ourselves as we prepare for the High Holy Days ahead:

Am I helping make my local community a favoritism-free zone?

Do I show respect and kindness to those I interact with, regardless of appearances?

Do I go beyond parochial altruism to learn the expansive altruism that reflects the character of Messiah Yeshua?