commentarY

The Upside-down Tent

Then that night, something crazy happened. The campsite was on a hill. My fellow campers and I had placed our tent on that hill, and we figured it was okay not to put our tent stakes in the ground because we were going to be inside it.

Parashat Yitro, Exodus 18:1 – 20:23

Gabriella Kaplan, virtual member, Ruach Israel, Needham, MA

Seeing the good in things can be incredibly hard. One of the hardest things the Jewish people had to endure was being slaves in Egypt and then having to travel through the wilderness. When Moses tells his father-in-law, Jethro, all that had happened to them in the wilderness and “all the hardships that had befallen them” (Exod 18:8) Jethro responds by rejoicing and praising God. As the Torah says, “And Jethro rejoiced over all the kindness that Hashem had shown Israel when delivering them from the Egyptians” (Exod 18:9). Never once does it mention that Jethro spoke about the trouble or “hardships” that the Jewish people had encountered on the way or the bad things they went through.

When something bad happens to me, my first instinct is to be upset or angry, as is human nature. What we learn from Jethro's response is that it is better to rejoice about the good moments than to worry or dwell upon the hardships that we have had to overcome to reach where we are now. We also can infer that Jethro wants us to learn from these hard moments by showing that in the end everything can work out for good.

At Camp Or L’dor, a Messianic Jewish camp I attend every summer, we go on a three-day adventure trip. These past couple of years we have canoed and kayaked on the Delaware River, and a year prior we backpacked around twenty miles on the Appalachian Trail. Before this trip, I had never backpacked a day in my life. The trip started off quite well—okay, maybe just the first five minutes went well. It went downhill from there (no pun intended). I wasn’t at all used to carrying a forty-pound pack on my back. Luckily, the first day was only a mile and a half hike to our campsite. I would love to tell you that the second day was easier, but it was not. The terrain got steeper, and we had to go much farther than the day before (thirteenish miles). Halfway through the day, we stopped for lunch at this beautiful gazebo at a little garden store, which allowed hikers to use the bathroom and take a break. It was wonderful. Then came the second half of the day. We hiked and hiked and finally neared our campsite. But not without another challenge. Toward the end of the day, the sun began to set, and we were all exhausted and starving. What lay in front of us was a steep incline that we needed to hike up in order to get to our campsite. One by one we all made it up the hill through the encouragement of our counselors and our fellow campers. Once we arrived we laughed and made dinner together.

Then that night, something crazy happened. The campsite was on a hill. My fellow campers and I had placed our tent on that hill, and we figured it was okay not to put our tent stakes in the ground because we were going to be inside it. At around 6 a.m. my friends and I awakened to the sound of laughter coming from our counselor who was taking pictures of us in the tent. At first, we were confused, then we realized that our tent had completely flipped over with us still in it. We all started to laugh as we got out of the tent to pack it up for our last day of hiking. Our last day was amazing; the terrain was mainly flat and we were all still in a good mood. We finished hiking the trail way earlier than expected, and, because it was the last day, we feasted on all the food that was left over as we waited to be picked up.

That trip was one of the best experiences of my life, and I learned to focus on the good and not the bad. I believe I grew from all the hard moments. Any time someone asks if I want to go backpacking, I jump at the chance because I never know what adventure I might have.

Paul reminds us, “Now we know that all things work together for good for those who love God, who are called according to His purpose” (Rom 8:28). All things do truly work out for good, especially when you are willing to take the time to reflect on the small moments in your life when God's lovingkindness and joy overpowers the unpleasant moments. If we can focus on the littlest happy moments, the small bits of good can outweigh the effects of the bad, and help us reflect and grow.

Like Jethro, we can exclaim, “Blessed be Adonai, who has delivered you out of the hand of the Egyptians and out of the hand of Pharaoh, and has delivered the people from under the hand of the Egyptians” (Exod 18:10). Jethro's example reminds us to focus on the good because, ultimately, we will remember the challenges but the positive moments will always stick with us. I could have focused on the steep hill and rough terrain, but the pleasurable moments like the encouragement of my counselors, the time with my friends, the joy of putting a tent on the hill and it tumbling down only hours later, and the amazing terrain and views were things worthy of praise to God. “Therefore, whether you eat or drink or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God” (1 Cor 10:31).

All Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version, TLV.

Faith on a Stretcher

Healing is a deep and universal human need, and praying for the sick and afflicted has always been part of my ministry as a rabbi and teacher—never more so than in recent years, with the Covid pandemic and a good number of friends and colleagues beginning to decline in health and vitality.

Parashat B’shalach, Exodus 13:17–17:16

Rabbi Russ Resnik

Healing is a deep and universal human need, and praying for the sick and afflicted has always been part of my ministry as a rabbi and teacher—never more so than in recent years, with the Covid pandemic and a good number of friends and colleagues beginning to decline in health and vitality. In the midst of this we’ve seen some remarkable answers to prayer, enough to keep me encouraged, although we’ve also seen some great losses as well. The Scriptures provide numerous verses that can fuel our prayers for healing, and one of my favorites appears in this week’s parasha: Ani Adonai rofecha—“I am Adonai who heals you” (Exod 15:26). Simple words, but they provide profound insights into the gift of healing and how to gain hold of it.

In context the passage doesn’t appear to be talking about the sort of healing I often pray for, recovery from physical or emotional/psychological injury or disease. Here, it’s part of nature, the waters of Marah, in need of healing, because they’re bitter and undrinkable, which leaves the Israelites in a desperate condition just days after they escaped from Egypt. Hashem shows Moses a tree; Moses casts it into the water; and voila!—the waters become sweet. Hashem tells the Israelites,

If you diligently listen to the voice of Adonai your God, do what is right in His eyes, pay attention to His mitzvot, and keep all His decrees, I will put none of the diseases on you which I have put on the Egyptians. For I am Adonai who heals you. (Exod 15:26 TLV)

At first hearing, these words seem to diminish the gift of healing, by making it contingent upon doing right, paying attention to the mitzvot, and keeping all Hashem’s decrees. But before we consider this apparent limitation of God’s healing, let’s ponder two lessons here that can help us get hold of healing today:

1. Healing is needed not just in our individual bodies and minds, but also at times in our environment. God’s creation is awesome and magnificent, but deeply damaged through the rebellion of the image-bearers God assigned to have dominion over it, namely us. We live in a broken world, a world of danger and disorder, but God’s healing power is at work within it.

2. This healing power is inherent to God’s character, or in biblical language, to his name—“I am Adonai who heals you.” Healing is not another deed that God does, but an aspect of who he is, so that when Hashem shows up in Israel as the man Yeshua of Natzeret, he immediately begins healing the people who come to him from all around (for example, Mark 1:32–34, 45; 3:9–10; 6:54–56).

So, we learn in our parasha that healing is not limited to diagnosable medical conditions, but is far more expansive, and that healing is an aspect of who God is, not just a kind deed he does now and then.

But questions remain—is healing as dependent on our good behavior as Exodus 15:26 seems to say? And what does Hashem mean when he talks about the diseases he put on the Egyptians? The language here reflects the reality of covenant, which God has already made with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and is about to extend to all the Israelites (Exod 24:6–8; 34:10–28). Covenant-making was part of the ancient world of the Near East and the terms of covenant were familiar. What’s unique—and amazing—here is a covenant that the one true God extends to unworthy humans. This is an unconditional act of hesed or grace, and it entails benefits of hesed, including healing. At the same time, this unconditional, hesed-driven covenant includes stipulations. This brings us to another lesson in healing from this week’s parasha:

3. To receive the fullness of covenant benefits, including healing, the Israelites must stay in right relationship with Hashem. In contrast, God has put diseases upon the Egyptians because the Egyptians, who live in the same broken world as the rest of humankind, are serving false gods who have no healing power at all. The Israelites have been brought into a right relationship with the one true God through his hesed, and they reap the benefits of that relationship through embracing his ways and serving him.

This seems like a straightforward reading of Exodus 15:26, but it worries me. It still sounds like we have to earn healing, and that if we remain sick or afflicted it’s our own fault. I don’t have the space for a whole discourse on this tough question, but an incident during Yeshua’s healing ministry sheds much light on it.

In Mark chapter two, Yeshua has returned to his home base in Capernaum after preaching all over Galilee, healing the sick and driving out demons. The house he’s staying in is soon thronged by crowds seeking to hear and see him, including four men carrying their paralyzed friend on a stretcher. They can’t get through the crowd to get close to Yeshua, but they don’t give up. A house like this would normally have a ladder or staircase to access its flat roof, and somehow the four comrades get their paralyzed friend up there. Then they put the stretcher down and dig through the layers of reeds and clay and branches resting on the roof beams. It’s a testimony to the noise level and intensity of the scene in the house that no one pays attention to what’s going on overhead until the friends break through and lower the stretcher down to Yeshua’s feet. Mark says that Yeshua saw their faith (2:5).

In Exodus 15, likewise our ancestors were to have faith you could see, by stepping out to cross the sea on dry ground, or by stopping their complaints against Hashem and his servant Moses. The admonition “do what is right in Hashem’s eyes” comes in the context of their complaining and unbelief—“Stop kvetching and cooperate with me!” Likewise, the friends in Mark didn’t just trust that Yeshua could heal; they did whatever it took to access his healing power—and that’s the trust/faith that Yeshua saw, faith-in-action.

Evidently, however, the paralyzed man doesn’t actually deserve healing because the first thing Yeshua says to him is “Son, your sins are forgiven.” Apparently he didn’t measure up. He wasn’t paying attention to the mitzvot and keeping all the decrees. Indeed, we might take his paralyzed state as a symbol of our spiritual condition, laid out on a stretcher and hoping only in God’s intervention—faith on a stretcher—which brings us to our fourth lesson:

4. Messiah Yeshua extends his healing gift to the unworthy and undeserving, if only they trust in him. The stipulations of Torah-obedience outlined in Exodus 15:26 are expressions of faith-in-action. And even when we fall short, Yeshua looks directly at the trust itself and responds with his healing touch.

So here’s a four-point takeaway from this week’s parasha:

We live in a broken world, a world of danger and disorder, but God’s healing power is at work within it.

This healing power is part of who God is, and it’s always near as he dwells among us.

We remain in a position to receive his healing touch as we keep our lives in alignment with his ways.

And even when we fall short, he will still see our trust and respond in compassion.

We may find ourselves paralyzed, laid out on a stretcher, but we can at least exercise enough trust to let ourselves be lowered down to Yeshua’s feet—and from there he reaches out to touch us.

Where is Your Heart?

On May 14, 1948, before signing Israel’s Declaration of Independence, David Ben Gurion looked back over 2000 years of our history and declared how the Jewish people had returned in a second exodus, “undaunted by difficulties, restrictions and dangers.”

Parashat Bo, Exodus 10:1–13:16

Ben Volman, Vice President of the UMJC

In 1936, David Ben Gurion addressed the British commission under Lord Peel, who was officially in Palestine to examine the reasons for local unrest. Ben Gurion understood that despite the original promises for a Jewish homeland, the delegation now had other priorities. Yet, with thousands of Jewish refugees flooding in from Europe to escape Nazi antisemitism, the Yishuv was building new cities, reclaiming the desert, and uniting under one language, Hebrew. Their success had led to violent Arab protests and the British wanted to hold them back, so Ben Gurion posed some questions:

The Mayflower’s landing on Plymouth Rock was one of the great historical events. . . . But I would like to ask any Englishman . . . what day did the Mayflower leave port? I’d like to ask the Americans: How many people were on the boat? Who were their leaders? What kind of food did they eat? More than 3300 years ago, long before the Mayflower, our people left Egypt, and every Jew in the world, wherever he is, knows what day they left. And he knows what food they ate . . . we tell the story to our children and grandchildren to guarantee that it will never be forgotten. And we say: “Now we may be enslaved, but next year, we’ll be a free people.”

Ben Gurion’s message was simple: you cannot stop us, for this freedom is already alive in our hearts.

Among all the epoch-making events in human history, there are few as compelling and impactful as Israel’s exodus out of Egypt. It is the touchstone narrative for people who have aspired to freedom across the globe. But in some ways, for those of us who have celebrated it every year throughout our lives, it’s almost too familiar. We sometimes rush toward the climax of the story, and don’t always take in all those essential details of the hard-won journey to freedom.

This parasha opens with the grating reminder that Moshe and his brother faced a persistent, unyielding adversary. Perhaps they were not so pleased to hear the Lord tell them: “Go to Pharaoh, for I have made him and his servants hard-hearted, so that I can demonstrate these signs of mine among them” (Exod 10:1).

Who wants to have the Lord deliberately make our mission harder? This was the great task before Moshe and Aharon: to keep facing Pharaoh’s resolute, “No!” After seven terrible plagues, he was warned, “Don’t you understand yet that Egypt is being destroyed?” (Exod 10:7). The eighth plague, an infestation of locusts, was utterly devastating: “Not a green thing remained, not a tree and not a plant in the field, in all the land of Egypt” (Exod 10:15). For a brief moment, the tyrant seemed to relent; then he did nothing. The ninth plague was even more overwhelming: three days of total darkness, “darkness so thick it can be felt” (Exod 10: 21). Again, after the sun’s light was restored, Pharaoh gave only the pretense of conceding. It was another “No.”

If there is one thing that has not changed after 3000 years, it is the obstinate nature of the human heart. We often look at Pharaoh’s stubbornness with an air of contempt, but it is a detail that ought to remind us of our own condition. As I prepared this d’rash, I had a long conversation with one of the Messianic rabbis whom I most admire, and he reminded me that the condition of our hearts before God is the most essential part of this story. Like Pharaoh, we think we can try to compromise or negotiate with God about our sins. But in the end, there is no way forward, no peace with him, no path to life until we surrender our hearts.

Everyone in the Exodus story has struggles of the heart with God, including Moshe in front of the burning bush and the Israelites, angry because their life had become harder after he told Pharaoh to let God’s people go. Finally, Moshe gives the Israelites all the instructions for the Passover, commanding them to cover their doors with the blood of the lamb.

When you come to the land which Adonai will give you, as he has promised, you are to observe this ceremony. When your children ask you, “What do you mean by this ceremony?” say, “It is the sacrifice of Adonai’s Pesach [Passover], because [Adonai] passed over the houses of the people of Isra’el in Egypt, when he killed the Egyptians but spared our houses.” (Exod 12:25–27)

As Rashi notes, the people seem to have finally understood that God was going to redeem them, bring them into the land of promise, and bless them with future generations. The verse continues: “The people of Isra’el bowed their heads and worshipped.” All those who had been wrestling in their hearts were now ready to surrender to God. This is the turning point, and the climax will soon follow.

The Peel Commission report of 1937 recommending the partition of Palestine between the Jews and Arabs was soon rejected and the British released a “White Paper” in 1939. Under the new policy, the British mandate admitted only a few thousand Jewish refugees per year. In North America, the U.S. closed its doors to Jewish immigrants and in Canada the government quietly adopted the principle of “none is too many.” The hearts of the world had grown cold, but that was not the end of the story.

On May 14, 1948, before signing Israel’s Declaration of Independence, David Ben Gurion looked back over 2000 years of our history and declared how the Jewish people had returned in a second exodus, “undaunted by difficulties, restrictions and dangers, and never ceased to assert their right to a life of dignity, freedom and honest toil in their national homeland . . . like all other nations, in their own sovereign State.”

Sometimes, our task is to believe that God’s work is not yet finished. On Friday, January 27, the world marks the UN’s Holocaust Memorial Day in remembrance of the 1945 liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. It is not a celebration of victory, but an inflection point in modern history, a moment when the world is called to consider past choices and ask, “Where were our hearts?” The prophet warns us, the heart “is more deceitful than anything else and mortally sick. Who can fathom it?” (Jer.17:9). We also have to answer, where are our hearts today?

The God in whom Israel have put their trust still confronts tyranny, still upholds justice, and will certainly deliver those who put their trust in him. This is perhaps the most profound message of all: God, who moves in our hearts, brings a meaning, purpose, and dignity to human life that no tyranny, no injustice can erase.

Scripture references are from Complete Jewish Bible, CJB.

Accepting Our Heritage

The life of Moses can be seen as three distinct movements, forty years each. First, Moses spends forty years thinking he is somebody. In the second act he discovers that he is nobody. But in the third forty years Moses discovers what Hashem can do with somebody who accepts he is nobody.

Photo by Edi Israel/FLASH90

Parashat Va’eira, Exodus 6:2–9:35

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Congregation Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

The life of Moses can be seen as three distinct movements, forty years each.

First, Moses spends forty years thinking he is somebody. He has fallen by providence into the royal court of Pharaoh, raised as a prince of Egypt, while his people, the Jewish people, suffer unbeknown to him.

In the second act he discovers that he is nobody. In a rather extended midlife crisis he winds up down and out, tending sheep in the wilderness among the tribes of Midian.

But it is in the third forty years of Moses’ life that he discovers what Hashem can do with somebody who accepts that he is nobody.

Parashat Va’eira begins as Shemot ended, with Moses returning to the presence of Hashem, pleading petulantly. Moses was sent to Pharaoh to demand the release of the Israelite slaves. But instead of releasing them, Pharaoh takes away their straw for brickmaking and they are absolutely outraged. Moses asks the Holy One how he might expect Pharaoh to listen to him, when even the children of Israel seem totally uninterested in his leadership. Moses goes so far as to accuse God of being unfaithful. “My Lord, why have you done evil to this people, why have you sent me? From the time I came to Pharaoh to speak in your name he did evil to this people, but you did not rescue your people” (5:22-23).

What appears to be an absolutely audacious indictment of the Holy One may just be indicative of the intended maturation of Moses.

By most normal measurements of success, Moses seems to be on a continual downhill spiral. He has gone from prince to outlaw, to sheep farmer, to dissident, to rejected and dejected labor leader. But something unique is happening in Moses. Instead of fleeing Egypt forever, Moses returns to the presence of Israel’s God to plead the case of a people that he has oddly identified with since his youth (2:11). Upon originally returning to Egypt to confront Pharaoh, Moses’ wife Zipporah circumcises their sons with a flint knife, a material act of identification into the covenant between God and Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. This timely interruption to the narrative suggests that Moses no longer sees himself as an appointed deliverer from outside the community of faith, rather as a fully enfranchised member of the family of Israel. In other words Moses has come to recognize and appreciate his heritage and his task.

What follows is a rebuke and an encouragement from Hashem that are in some ways indistinguishable from each other.

God spoke to Moses saying, “I am Hashem. I appeared to Abraham, to Isaac, and to Jacob as El Shaddai, but with my Name Hashem (YHVH) I did not make myself known to them.” (6:2-3)

Prior to calling Moses into service, as the Torah informs us, God “remembered the covenant with the patriarchs” (2:24), but now the disclosure of the Divine Name establishes the covenant with Moses as part of the natural progression of the patriarchal covenant. Moses and Israel are entering into their inheritance together.

Hashem then promises that the land of Canaan will be part of the inheritance; it will be Eretz Yisrael—the land of Israel (6:4). Then, after stating his intention to liberate Israel and take them for his people, Hashem declares again concerning the land, “And I shall give it to you as a heritage (morashah)” (6:8). This Hebrew term, morashah, heritage, appears twice in the Torah. It is first mentioned in relation to the Land of Israel, and later in Devarim 33:4, in connection with the giving of Torah. The term morashah is used in two places to teach us that the heritage represented by the Land of Israel can remain ours only if we commit ourselves to the keeping of Torah.

In the same way that Moses the liberator, law-giver, and teacher needed to mature into his heritage as a fully enfranchised member of Hashem’s Holy Nation, so we, the sons and daughters of Israel, must mature into our heritage as well. The promises of morashah, Land and Torah, are inseparable. The thrice-daily prayer Alenu declares that our inheritance is our task. We are called to be a light to the nations, to draw all people to the service of the one true God. This is our heritage, this is our call, and it cannot be measured by any of the normal standards.

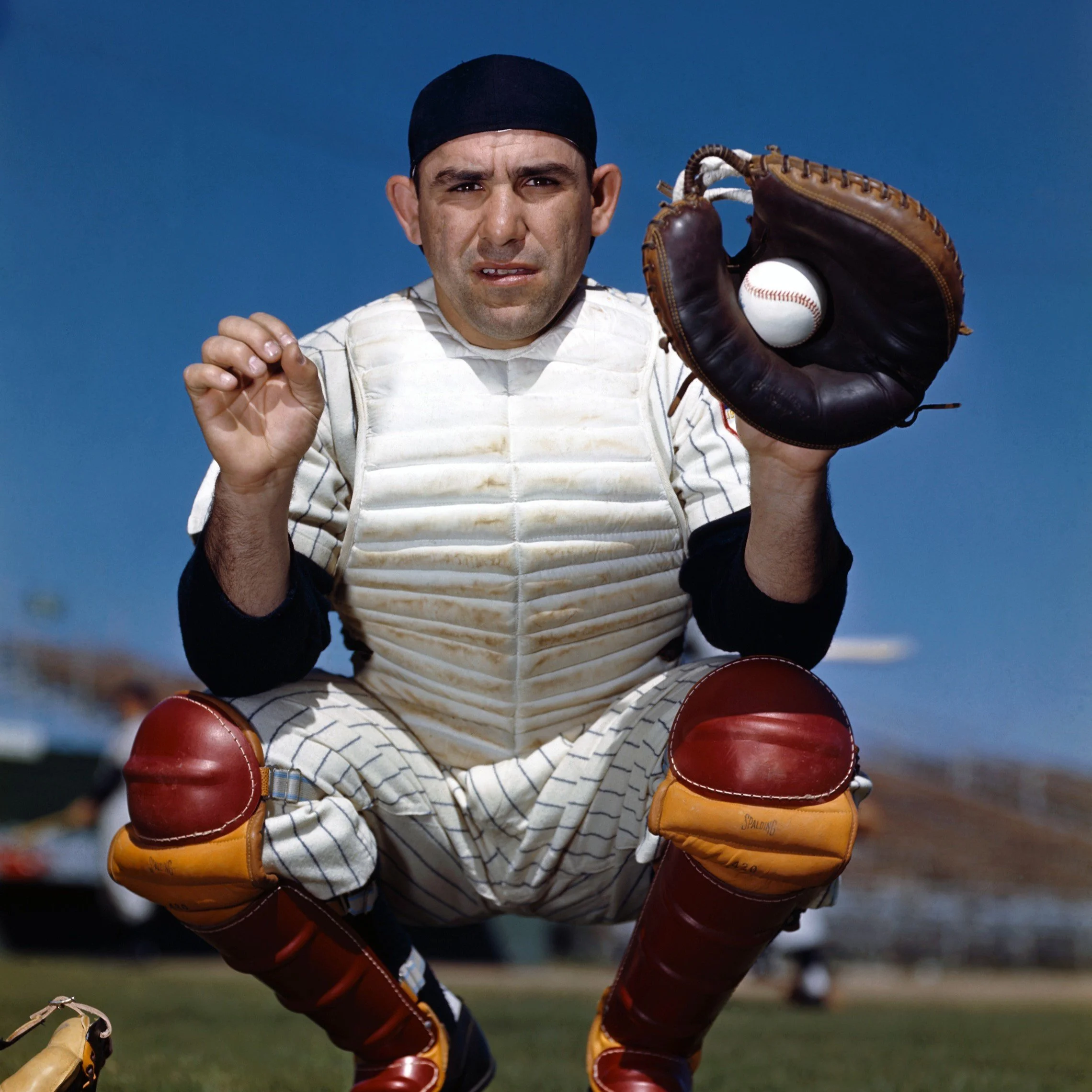

Yogi Berra, Making the Pitch, and Telling Stories

The Prophet Yogi Berra told us, “You can observe a lot by just watching.” Such sage advice! But it is true that we can learn a lot for our own lives by watching how our ancestors lived theirs.

Parashat Sh’mot, Exodus 1:1–6:1

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann, Ahavat Zion Messianic Synagogue, Los Angeles

The Prophet Yogi Berra told us, “You can observe a lot by just watching.” Such sage advice! But it is true that we can learn a lot for our own lives by watching how our ancestors lived theirs.

That’s how it is with a cluster of verses from our parasha where Moshe meets with his brother whom he has not seen in forty years. The encounter is arranged by Adonai himself, and its details outline seven lessons in what it means to share our faith with others.

To learn those lessons, we must travel to Sinai.

Adonai said to Aharon, “Go into the desert to meet Moshe.” He went, met him at the mountain of God and kissed him. Moshe told him everything Adonai had said in sending him, including all the signs he had ordered him to perform. Then Moshe and Aharon went and gathered together all the leaders of the people of Isra’el. Aharon said everything Adonai had told Moshe, who then performed the signs for the people to see. The people believed; when they heard that Adonai had remembered the people of Isra’el and seen how they were oppressed, they bowed their heads and worshipped. (Exod 4:27–31)

What are our lessons in faith-sharing?

Faith-sharing happens within divinely-ordained encounters. God arranged the meeting between Moshe and Aharon. And we should be on the lookout for how God works in our lives to arrange situational set-ups where sharing our faith with others fits the occasion. We might share our faith out of some pervasive anxiety to do so. When we do, the encounter may not be about the one we’re sharing with but about our need to say something. But there are people around us whom God has ripened for our mutual encounter. We should pray for eyes to see and hearts to respond to the occasion.

Faith-sharing best occurs within a prior relationship, as demonstrated by Moshe and Aharon. These relationships may be with family or with friends. Sharing the knowledge of God is highly personal. Little positive and too much negative is accomplished through buttonholing strangers. Look at it this way: sharing the good news of Yeshua is an act of love, an intimate encounter. No matter what our intention, if we ignore this, our faith-sharing may come across not as an act of love, but as an assault. Not good.

But what is faith-sharing? At its root, it is telling stories, the story of Yeshua and the story of our life-renewing encounter with God through him. Patrick Henry Winston, head of the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at M.I.T., taught that what sets humans apart from all other mammals is our capacity to construct and tell stories. If storytelling is central to our humanity, shouldn’t we then share our faith with stories about Yeshua, who he is and what he has done? And shouldn’t we tell our friends stories of our own encounters with him? Yes, we should. That’s what Moshe does here with Aharon, and what he will do later, when he shares his faith with his father-in-law (Exod 18:8–9). Elie Wiesel said that God created people because he loves stories. We should show our love and God’s love to people by storytelling. It’s the human thing to do.

Faith-sharing includes demonstrating the power. People need more than a story. They need to know God is real. Moshe received from God an ability to do miraculous signs. This was a crucial aspect of the storytelling, because the One at the center of the story is a miracle-working God. We can see that this is so by considering the apostles. They lived with Yeshua as his story was unfolding, but that was not enough. When Yeshua asked Peter (Shim‘on Kefa) and the rest of the apostles who they thought he was, “Shim‘on Kefa answered, ‘You are the Mashiach, the Son of the living God.’ ‘Shim‘on Bar-Yochanan,’ Yeshua said to him, ‘how blessed you are! For no human being revealed this to you, no, it was my Father in heaven’” (Matt 16:16–17). Peter knew Yeshua’s developing story, but to come to faith in him, he needed more: he needed to experience the revelatory power of God. So will it be with our friends. This is why we simply must pray for God to show up in the mix, trusting that he can make himself real to the persons with whom we share.

This is a message to be passed down the line. When Moshe and Aharon spoke to the people of Israel, it was Aharon who relayed the story Moshe had told him. This is how faith-sharing happens. One person tells another who then tells others.

This good news fulfills ancient promises. The message Aharon passed on to the oppressed Israelites was no novelty. It was a confirmation of promises made to them long ago. This is why we must share the good news of Adonai’s saving work in Yeshua as something new, which is at the same time linked to ancient words and eternal purposes. It is no gimmick, but the flowering of eternity’s seeds.

Finally, the evidence that the good news we reported takes root in people’s hearts is not simply that they nod their heads in agreement, walk forward, or raise their hands. The evidence includes a new birth of worship that confirms that the Ruach is at work.

Almost sixty years ago, I participated in a panel discussion with the great J. I. Packer, who spoke indelible words I still remember. He said, “Don’t ask me to believe that a person who walks forward at a meeting is a Christian (or, in our terms, a Messianic believer). The evidence of being a child of God is that the person prays and worships God.”

We would do well to think about this, that the new birth is a new birth of worship. This comes from the seed of the word, embodied in the stories we tell.

Shim’on Kefa, Peter, of whom we spoke earlier, put it this way in one of his letters:

You have been born again not from some seed that will decay, but from one that cannot decay, through the living Word of God that lasts forever. For

all humanity is like grass,

all its glory is like a wildflower —

the grass withers, and the flower falls off;

but the Word of Adonai lasts forever.Moreover, this Word is the Good News which has been proclaimed to you. (1 Peter 1:23–24)

Let’s go and tell some stories, sure that the God of Sinai goes with us.

Scripture references are from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

God Already Knows, but He’s Waiting to Hear from Us

God knows all things, but he has assigned to human beings, and therefore to us, a priestly responsibility. Even though our ancestors were groaning under heavy bondage, they still represented God and had the authority to call upon him to intervene.

Parashat Vayechi, Genesis 47:28–50:26

Rabbi Russ Resnik

In the next-to-last scene of the old Star Wars movie, The Empire Strikes Back, the hero, Han Solo, is frozen solid in carbonite by his imperial captors. As he is lowered into a vault, a frosty mist swirls about him and the music fades away. All you can think is, “sequel coming.” It seems like a moment of defeat, but it signals the victory that is sure to come.

Like The Empire Strikes Back, Genesis concludes with an image of seeming defeat—in this case a coffin—that conveys the promise of victory to come. The last two verses read,

Then Yosef took an oath from the sons of Israel: “God will surely remember you, and you are to carry my bones up from here.” So Yosef died at the age of 110, and they embalmed him and put him in a coffin in Egypt. (Gen 50:25–26)

At first glance this seems like a negative ending for the magnificent first book of the Torah. The rabbinic commentators do not say a great deal about it, perhaps reflecting some embarrassment at the fact that Joseph is embalmed, in contradiction to later Jewish law. Christian commentators often see the conclusion of Genesis as negative, suggesting the hopelessness of the human condition apart from divine redemption.

The book of Hebrews however, provides a key to understanding this conclusion: “By trusting, Yosef, near the end of his life, remembered about the Exodus of the people of Israel and gave instructions about what to do with his bones” (11:22).

The coffin in Egypt becomes an emblem of hope, a sure sign that this story is not over yet. Joseph “remembered about the Exodus of the children of Israel” assuring them that God would “surely remember” them and bring them up out of Egypt. God promises redemption, and Joseph believes that promise.

As Genesis concludes, then, we may believe that we have only to wait for the sequel, when the promise will surely be fulfilled. In the Book of Exodus, however, we learn that something else must happen first:

It was, many years later,

the king of Egypt died.

The children of Israel groaned from the servitude,

and they cried out;

and their plea-for-help went up to God from the servitude.

God hearkened to their moaning,

God called-to-mind his covenant with Avraham, with Yitzchak, and with Yaakov,

God saw the Children of Israel,

God knew. (Exodus 2:23–25, Schocken Bible)

The simple language of Torah describes God as taking four actions. The children of Israel groan, and the Lord hears, remembers, looks, and knows. Of course, God knows everything all the time. Hence, numerous translations supplement this final phrase, with words like, “God took notice of them” (JPS, 1967 ed.), or “God acknowledged them” (CJB). But the Hebrew is clear enough: “God knew,” period.

Indeed, God knows all things, but he has assigned to human beings, and therefore to us, a priestly responsibility. Even though our ancestors were groaning under heavy bondage, they still represented God and had the authority to call upon him to intervene on the earthly plane. This is the most basic sense of intercessory prayer. In Exodus, furthermore, we learn that the intervention they called for would involve a struggle against the demonic powers upholding Pharaoh’s dynasty, and holding the Israelites in bondage. As the Lord says, “I will execute judgment against all the gods of Egypt; I am Adonai” (Exod 12:12).

Beyond this basic intercession, we can see a second level, reflected in the traditional prayers that we recite every week. Even after our redemption from Egypt, we remain in exile and bondage, but we can go beyond simple groaning. We have the promise of victory and redemption revealed in Scripture, and can invoke that promise and call upon the Lord to intervene. It’s not clear whether our ancestors in Egypt even remembered the promise of redemption, until Moses came to deliver them, but God heard their anguished groaning. Now, however, we have the assurance of redemption revealed in Scripture, and call upon God on that basis.

Our liturgy is filled with examples of this intercessory outcry. The final line of the Kaddish, also repeated at the end of the Amidah, says, “He who makes peace in the heavenly realms, may he make peace for us and for all Israel.” Peace, the shalom that prevails already in the heavenly court, is central to the prophetic vision of the Age to Come. In the daily prayers, we call on Hashem to establish that shalom in our midst even now. When we sing this prayer, we repeat the refrain, ya’aseh shalom, ya’aseh shalom, shalom alenu v’al kal Yisrael, literally, “He will make peace upon us and upon all Israel,” a prophetic and intercessory cry for the Lord to do what he has promised.

Likewise, before we take the Torah out of the ark, we recite the words, “And it came to pass, whenever the ark went forward, Moses would say, ‘Arise O Lord, and let your enemies be scattered. Let those who hate you flee before you.’” As the word of God goes forth, we pray that the spiritual forces that oppose God and Israel—“the gods of Egypt”—will be defeated and driven back. In this weekly enactment, we are interceding for all Israel, and ultimately for the whole human race, looking forward to the day when “The Torah will go forth from Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.”

With such prayers Israel has taken on its priestly responsibility throughout the centuries, and they remain most valuable in the sight of God. We do well to participate in them, especially as we do so in union with Messiah, who is the true high priest and intercessor. Through him these prayers will be fulfilled in the end, and through him we come to a third level of intercession.

The first level is what we see in the parasha, the simple groaning of Israel, crying out to God for relief. A second level of prayer comes in response to the promises revealed in Scripture. We cry out in the language of divine revelation to remind God to act as he has said he would. The third level is a response to the fulfillment of the promise in Messiah Yeshua. We still await the Age-to-Come, but in Messiah there is a present-day reality, the victory over demonic forces through his death and resurrection, which brings redemption in this age.

God already knows all things, but he’s waiting to hear from us. It is our priestly responsibility to remind him of his promise, and to proclaim the fulfillment of that promise in Messiah Yeshua.

Adapted from Creation to Completion: A Guide to Life’s Journey from the Five Books of Moses, Messianic Jewish Publishers, 2006.

Scripture references, unless noted, are from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

Hope Can Set You Free

Who among us hasn’t contemplated revenge? Who hasn’t caught themselves musing at length about toppling an enemy from their pedestal, wanting them to feel for a moment the same pain that they inflicted? When Yosef was hauled off to prison at the whim of Potiphar’s wife, who do you think he blamed?

Parashat Vayigash: Genesis 44:18–47:27

Ben Volman, UMJC Vice President

Who among us hasn’t contemplated revenge? Who hasn’t caught themselves musing at length about toppling an enemy from their pedestal, wanting them to feel for a moment the same pain that they inflicted? When Yosef was hauled off to prison at the whim of Potiphar’s wife, who do you think he blamed? Almost certainly, it would have been those brothers who callously sold him into slavery. After 13 years in Pharaoh’s jail, he had lots of time to imagine how to get even, if he ever got the chance.

As our story opens, it appears nothing can stop him. He’s already played with his brothers’ worst fears and though he’s a stranger, they have come to feel that somehow this Egyptian is an instrument of God’s judgment. They are about to watch him do to Binyamin what they once did to Yosef: make him a slave and send them away to explain the loss to their father.

At this crucial moment, Y’hudah steps forward (Gen 44:18). The Hebrew word “vayigash,” usually translated as “he approached,” carries unusual depths of meaning. One key midrash (Genesis Rabbah 93:6) reminds us that it may be used for entering battle (2 Sam 10:13), to reconcile (Josh 14:6), or to pray (1 Kings 18:36). The word also introduced another timely act of intercession, when Avraham “came forward” to intercede for the righteous who may yet be in Sodom (Gen 18:23).

Y’hudah’s speech is a master class in humility. He makes neither excuses nor any argument to explain or blame. Humbly he lays out the story of his promise to a grieving father, pleading for mercy on behalf of a heartbroken old man. All hope now lies in the hands of Pharaoh’s vizier.

If Yosef had been set on revenge, would this speech have moved him? Perhaps not. But what was in his heart? What happened during those years in prison? We have one important clue: when Pharaoh speaks to Yosef as one with power to interpret dreams, Yosef replies, “It isn’t in me. God will give Pharaoh an answer that will set his mind at peace” (Gen 41:16). This is not the same young man who once boasted of his dreams. These are words of a tested faith worthy of Avraham’s spiritual heir. All his hope is in God and he understands that God draws near to those who know him with shalom shalom, his perfect peace (Isa 26:3).

When I read Anwar Sadat’s memoirs, I was moved by his remarkable account of 31 months spent in a Cairo prison that transformed his life. Conditions in Cell 54 were horrific and disgustingly unsanitary, and prisoners came out for only 15 minutes a day. But in that time, Sadat (only 27 when he entered prison) developed a relationship with his inner self and with his Creator; a loving trust in God that guided the rest of his life. That experience gave him an internal resilience to become the first Arab leader to go to Jerusalem and sign a genuine treaty with Israel.

It’s impossible to know how Yosef found the way to hope and forgiveness in his dungeon. But when he heard Y’hudah’s appeal for mercy, Yosef knew that his brothers were changed. Still, his response came with great pain. Yosef’s long-buried, pent-up emotions overwhelmed him, and he had to order everyone from the room but the captive Hebrews.

Why was it so hard? Until his brothers arrived, Yosef was missing a part of himself. Despite the blessings of God’s presence, he yearned to fulfill his larger purpose as a son of Avraham. God brought his brothers—his betrayers—to restore his lost identity. They alone understood that when he said, “I am Yosef” he was saying, “No matter what you did, you are still my brothers.”

Finally, he could share the profound insight of faith that had given him the freedom to forgive. That is why he immediately declares: “Do not be distressed or reproach yourselves . . . it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you. . . . It was not you who sent me here, but God” (Gen 45:5–8). Yosef may have once wanted revenge, but he had given it up for something greater: he was at peace with God’s gift of a higher purpose.

When I consider how Israel’s future depended on the mercy of a man betrayed by his own brothers looking into the face of the one who sold him into slavery, my old resentments and aging grudges come into painful focus. Yosef spent 13 years in prison—how many years have we locked away some part of ourselves from grace?

One of Elie Wiesel’s German graduate students asked him, “Do you never feel hatred for the German people?” Wiesel replied, “You must turn hatred into something creative, something positive. . . . Express what you feel and let the hate become something else. But do not hate.” After miraculously surviving the Ravensbrück concentration camp, Corrie ten Boom set up a recovery home for fellow survivors. She recalled how those who took hold of life again had hearts to forgive. Those who stayed bitter remained trapped in the past.

We have all gone through waves of trauma over the past three years. I think of dear friends struggling with loss; some who are living with long Covid; others toiling faithfully for the suffering people of the Ukraine. But let’s not lose sight of hope. When Sadat arrived at Ben Gurion airport in November 1977, he had a special greeting for his familiar adversary of the Yom Kippur War, Golda Meir: “I have wanted to meet you for a long time,” Mr. Sadat said. Mrs. Meir replied: “Mr. President, so have I waited a long time to meet you.” He leaned over and kissed her on the cheek.

As the calendar turns over, I can’t think of anything more important than taking hold of hope and the words of Yeshua that lead me to pray: Lord, help me to let go of what needs to be given over to you and to forgive as I’ve been forgiven. Amen and Happy New Year.

All Scriptures are taken from the Complete Jewish Bible.

Light over Might

Let’s make no mistake; the Maccabees did not fight for religious freedom, but to cleanse the land for the worship of the one true God of Israel. While they fought to end the Greek cultic practices imposed through the tyranny of Antiochus, they also fought to end the long-felt effects of assimilation.

Hanukkah 5783

Rabbi Paul Saul, Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

One of the primary messages of Hanukkah is to avoid assimilation at all costs. But how often do we hear that the Hanukkah story is about religious freedom? As if any religion would have been OK, so long as everyone got to choose for him or herself. Is that really true? Can we possibly imagine old Mattathias, leader of the Maccabees, accepting a compromise whereby the east wing of the temple would have offered kosher sacrifice, while, in the spirit of pluralism, the Hellenistic Syrians were featuring pork barbeque on the west side?

Let’s make no mistake; the Maccabees did not fight for religious freedom, but to cleanse the land for the worship of the one true God of Israel. While they fought to end the Greek cultic practices imposed through the military tyranny of Antiochus, the Syrian Greek ruler, they also fought to end the long-felt effects of assimilation. The hard-to-swallow truth is that many Jews then, as today, envied the freedom and fanfare of the nations, and were all too happy to put off the yoke of Torah. The war opposed the attractive popular spectacle of uncircumcised Jewish athletes in public sport as much as it did the forced sacrifices to Zeus in the Great Temple. It should not surprise us then that the greatest miracle of Hanukkah is not the immediacy of military triumph, but the sustenance of the divine light.

Perhaps the tradition surrounding how we light the Hanukkah menorah, or hanukkiah, can illuminate (pun intended) this point. One candle is lit the first night with the number of candles increasing each successive night. This is the tradition handed down from the School of Hillel (Shabbat 21b) and accepted by most practicing Jews in the world today. The School of Shammai, in contrast, held that all eight candles should be lit on the first night, and the number of candles should diminish by one each successive night. This view seems logical since each night the sanctified oil used to light the menorah in the Temple would have diminished. But then this would assume that there was enough oil to light the menorah in the first place.

Hillel argues that each night more oil was necessary to light the lamp, so the magnitude of the miracle increased. This follows the Jewish concept of the ascendancy of holiness. Since lighting the Hanukkah candles is a holy act, each night the holiness increases and so therefore should the number of candles.

The two schools of thought punctuate the two-pronged nature of the Hanukkah miracle as identified in the prayer Haneirot Halelu, recited after lighting the menorah each night. The first part states, “these lights we kindle to recall the wondrous triumphs and the miraculous victories wrought through your holy priests for our ancestors in ancient days at this season.” At Hanukkah we acknowledge that God, as is often his style, “gave the strong over into the hands of the weak.” The second part of the prayer goes on to say, “these lights are sacred through all eight days of Hanukkah. We may not put them to ordinary use but are to look upon them and thus be reminded to thank and praise you for the wondrous miracle of our deliverance.” It encourages us to look upon the miracle of maintaining the Jewish people in the face of ongoing assimilationist influences. The real miracle of the lights is that they do not end in eight days; rather, we are encouraged to become participants with God in our own spiritual deliverance by directing our attention to praising him and remembering him as he remembers us.

We might infer that the school of Shammai emphasizes the military victory. Though important, however, the effects of physical victory quickly fade, leaving few lasting results. We have seen this in our own times. How often has the U.S. military machine removed a rogue dictator only to fight the “democratic regime” that succeeds him within a quarter of a century? In the same way, history records that the Maccabees, the so-called champions of religious freedom, became strong-armed dictators of religious oppression in Israel during the century that followed. So by lighting eight candles on the first night and decreasing the number each night after, we observe the diminishing power of military might.

Spiritual power, on the other hand, begins modestly and is often barely noticed, then increases over time and slowly displays its lasting effects. By lighting the candles in ascending order as Hillel suggests, we illuminate (there I go again) the more efficacious nature of the spiritual miracle—the power of the spirit grows day by day.

As it was for the Maccabees, so it is for us. We have a culture that continually attempts to seduce us into believing that true power is in wealth and influence. We American Jews try our hardest to look and act like our neighbors. We crowd the malls this time of year with the same deliberate worship of consumerism as our neighbors, losing the true spiritual meaning of Hanukkah.

But let me not just pick on our Jewish people. What of the Christians across the country who advocate boycotting retail stores unless they put the name Christmas back in their holiday advertisements? I think I missed something here. Shouldn’t believers in Yeshua boycott stores that even imply any connection between the Christ Child and consumerism? After all, wasn’t Yeshua the greatest counter-culturist of them all? When the exuberant crowds called out for a military hero like Judah Maccabee, didn’t he respond by laying down his own life? When Caesar, like Antiochus, sought to grasp divinity and make himself the object of worship, didn’t Yeshua selflessly empty himself into the form of a servant, only to be exalted to the right hand of God on high?

Shouldn’t we then as Messianic Jews during this season become imitators of Yeshua, separating ourselves from the basest tendencies of our culture? Can’t we suffer the indignation of being different from our neighbors for the sake of God’s kingdom? Do we seek after the fading victories of military might and conspicuous wealth, or will we seek God’s higher standards?

This year as we light the menorah on the eighth night of Hanukkah, let’s remember the greatest miracle of the season, that God has sustained his light among his people Israel despite the best efforts of both militant tyrants and seductive assimilationists, recalling the words from the traditional reading for Chanukah: “Not by might nor by power, but by my Spirit, says the Lord of hosts” (Zechariah 4:6).

What Would the Maccabees Do?

When our Gentile friends or co-workers ask us “what’s Hanukkah about, anyway?” we tend to give them sugar-coated references to light, miracles, and funny games with spinning tops. But this is only half of the story.

Hanukkah 5783

Monique B, UMJC Executive Director

Hanukkah begins on Sunday night and lasts eight nights, and this year our very minor Jewish holiday overlaps with a very major Christian holiday. You may have heard of it.

Jewish people have enjoyed a sense of welcome, limited at times, within American society since before our nation’s founding. As a result, we have developed a uniquely American way of celebrating Hanukkah, with eight nights of gifts to our children (to rival the Gentiles’ haul of gifts under their trees), Hanukkah-themed decorations for sale at the local Target or Bed Bath and Beyond, and Chabad-sponsored menorah lightings in our town squares.

When our Gentile friends or co-workers ask us “what’s Hanukkah about, anyway?” we tend to give them sugar-coated references to light, miracles, and funny games with spinning tops. But this is only half of the story.

The full story of Hanukkah must include the catalyst: a tyrant invaded our ancestral land and made our way of life illegal. He offered wealth and power to Jewish priests and landowners, in exchange for tolerating the subjugation of pious Jewish peasants. In so doing, he corrupted our priesthood, paving the way for a complete desecration of our sacred Temple, making it impossible for us to make kosher sacrifices on a tainted altar. Soon his regime outlawed circumcision of infants and the study of our sacred texts. Antiochus’ soldiers occasionally forced random Jewish leaders to make pagan sacrifices in front of their neighbors, a potent humiliation tactic. If his regime had remained for a generation or two, the unique way of life of the Jewish people would have been forever erased. The Messiah would not have come. The nations would still be worshiping rocks and sticks.

Under Antiochus’ regime, many of our people accommodated the new reality for the sake of survival. They pretended to be good pagans in public, and held on to the scraps of Judaism they could still practice in private. But a band of religious zealots planned a rebellion in the caves of Judea, and waged a prolonged campaign of guerilla warfare that finally drove out the occupiers. When we recaptured Jerusalem, we had to immediately contend with our polluted Temple. Before our way of life could be restored, before a single sacrifice could be made on the rebuilt altar, before anyone could seek ritual purification, the eternal flame of the Temple menorah had to be relit. And so it was, and so we endured as a stubbornly resilient people. Foreign empires be damned.

For over two thousand years we have dared to light miniature menorahs and display them outside our homes, not as an act of nostalgia, or an attempt to compete with Santa, but as an act of defiance. Throughout our people’s history we have been beaten down by tyrants who seek our extermination. Every civilization that has sought our destruction has become a memory to be studied in dusty museum archives. But we are still here. The people of Israel live.

As antisemitism rises around the world, it is right for us to remember this era in our people’s history. It is no longer safe to be Jewish in Putin’s Russia—the Jewish community is leaving in droves. On the subways and streets of New York City, Jewish people are attacked once every 16 hours. In the last few weeks, those attacks have increased in ferocity and in frequency, inspired by Kanye West and Kyrie Irving’s endorsements of Black Hebrew Israelite ideology—which preaches that the “real” Jews are black Africans, and that we are the fakers. On the airwaves, and on social media platforms like Twitter, Telegram, Gab, and Truth Social, antisemitism and Holocaust denial are trending.

Everywhere that Jewish people have ever gone, in every society where we have sought asylum, the welcome mat has eventually been pulled. We are too strange and too stubborn to fit into Gentile societies—this was true for our patriarchs and matriarchs, for Moses, Daniel, Esther, and the Maccabees. It is still true today. Our very identity predates the concepts of race, religion, and nationality. So we are eternally treated as a “problem” to be solved. And our enduring survival in spite of everything they have thrown at us aggravates our haters even more.

What are we to do, as Messianic Jews living in 21st century America, when antisemitism is trending? We tread on especially treacherous ground, because some antisemites call themselves Christians, and for them, we are the only “acceptable” kinds of Jewish people, due to our fidelity to Yeshua. Sometimes they visit our synagogues, pray alongside us in our pews. If they stick around long enough, they inevitably heckle and pester us about our unique mission. “It’s too Jewish,” they say. “Too Jewish,” like that’s a bad thing. “Too Jewish,” as if it’s ever remotely possible for a synagogue, of all places, to be too Jewish.

What should we do when we face people like this? How do we discern our friends from our foes in such a turbulent environment? Should we serve as tokens for antisemites who call themselves Christians, enjoying a limited sense of elevated status in their midst? Should we depend on their donations and make excuses for their ignorance? Or do we have a special duty to correct their skewed perspective, and call them to make teshuva?

If our community is going to stand for anything, if it is going to mean anything in the broad scope of human history, and in the kingdom of heaven, let it be this: that it is entirely impossible to follow the Messiah of Israel while harboring resentment, envy, or hatred for the people of Israel. If we are going to be known for anything, it should be for making our homes, our neighborhoods, even our workplaces, more Jewish than we found them.

As you light your Hanukkiah this weekend, place it proudly in your windowsill. When your neighbors ask, “What’s Hanukkah all about anyway?” tell them that a tyrant invaded our ancestral land and tried to make our way of life illegal. We drove him out, and he met the same fate as everyone across history who has sought our destruction. We’re lighting these candles to thank the God of Israel for the miraculous and enduring survival of the people of Israel. Our people have walked through endless trials, and we’re still here. If that’s not abundant evidence for the existence of God, then nothing is.

As we add to our daily prayers during the week of Hanukkah:

You delivered the mighty into the hands of the weak, the many into the hands of the few, the impure into the hands of the pure, the wicked into the hands of the righteous, and the degenerates into the hands of those who cling to your Torah. And you made for yourself a great and holy name in your world, and performed a great salvation and miracle for your people Israel, as you do today.

“Turned into Another Man”

A little old Jewish lady decides to make the long journey to speak with a holy man in India. When she arrives, his attendants turn her down—the guru is thronged by admirers—but she is so insistent that they finally let her in on one condition: she can only speak three words.

Baba Ramdev, Photo by Sam Panthaky/AFP.

Parashat Vayishlach, Genesis 32:4–36:43

Rabbi Russ Resnik

A little old Jewish lady decides to make the long journey to speak with a holy man in India. She flies into New Delhi and takes a train to a small town in the mountains, where she catches a rickety old bus for another leg of the journey. At the end of the bus line, she hires a porter to schlep her bags as she walks the last few miles. Finally, she arrives at the ashram and demands to speak with the guru right away. His attendants turn her down—the guru is thronged by admirers—but she is so insistent that they finally let her in on one condition: she can only speak three words. “Fine,” says the old lady. When she comes before the holy man, she looks up at him and says, “Sheldon, come home!”

People of all sorts long to escape the commonplace and be transformed into someone more holy. What they often discover, however, is that such a change can only come from an encounter with something—or someone—beyond themselves. The Torah speaks of just such encounters.

Thus, our last parasha opened with Jacob departing from the land of promise. As night falls, the text says literally, “he encountered the place” (vayifga bamakom; Gen 28:11). Jacob spends the night in that place and has a vision of a ladder joining heaven and earth. He recognizes that in reality he has encountered God, sometimes named in rabbinic literature as HaMakom, or the Place. This encounter with HaMakom prepares Jacob for the journey that lies before him. At the end of the parasha, as Jacob is about to return to the land, we see the same verb: “And angels of God encountered him” (Gen 32:2). Now he will be prepared to return to the land from which he departed decades before.

“Encounter” in these contexts implies something out of the ordinary, the heavenly realm breaking into the earthly. Jacob is not equipped for his departure or his return without this heavenly breakthrough.

We see the same verb in the story of King Saul. Samuel anoints him as king and sends him back to his father’s house to await the time of his public revelation. Samuel tells Saul that he will “encounter a band of prophets . . . Then the Spirit of the Lord will come upon you, and you will prophesy with them and be turned into another man” (1 Sam 10:5–6).

“Turned into another man . . .”—this is the appeal of Jacob’s story. We might believe there is a transformed world waiting, the restored Creation of which the Scriptures speak. But like Jacob—and Sheldon—we desire transformation for ourselves. In the end, we learn that only a divine encounter will make us different people.

More than the other patriarchs, Abraham and Isaac, Jacob is like us. Abraham, despite the flaws that Genesis honestly reports, appears on the scene as a visionary from the very first, a pioneer of faith in the one true God. Isaac is more passive, but he never veers from the faith of his father Abraham. Jacob, in contrast, is the patriarch with whom we can most identify, the Everyman of Genesis. Like us, he is a person in process. His potential for greatness is evident, but nearly always mixed with qualities that are more ordinary.

Thus, for example, Jacob has the greatness to recognize and desire the spiritual legacy of his father Isaac, unlike his brother Esau who despises his birthright (Gen 25:34). But he gains the birthright ignobly, taking advantage of Esau’s shortsightedness to buy it for a bowl of lentil stew, and colluding with his mother’s deception to gain Isaac’s blessing. It will take twenty-two years serving the wily Laban to transform Jacob into the man who can return to the Promised Land and take up the legacy of his forefathers. We may sympathize with his trials at the hand of Laban, but we realize that they are necessary—just like the trials that mold us.

In Parashat Vayishlach, however, we learn that such trials do not give the final shape to Jacob, but the divine encounters do. This parasha is a tale of homecoming. Jacob discovers that you can come home again, but you cannot come home unchanged. The Jacob who returns is different from the Jacob who departed:

So Jacob remained all by himself. Then a man wrestled with him until the break of dawn. When He saw that He had not overcome him, He struck the socket of his hip, so He dislocated the socket of Jacob’s hip when He wrestled with him. Then He said, “Let Me go, for the dawn has broken.”

But he said, “I won’t let You go unless You bless me.”

Then He said to him, “What is your name?”

“Jacob,” he said.

Then He said, “Your name will no longer be Jacob, but rather Israel, for you have struggled with God and with men, and you have overcome.” (Gen 32:25–29 TLV)

Jacob undergoes two changes on his way home. His hip joint is dislocated, and his name is changed. Over the centuries commentators have discussed whether Jacob’s injury is permanent, but it’s clear that God touched Jacob and left a mark on his soul that he would never forget.

Jacob’s renaming has also evoked endless discussion, along with a variety of different translations, such as that of Everett Fox:

Then he said:

Not as Yaakov/Heel-Sneak shall your name be henceforth uttered,

but rather as Yisrael/God-Fighter,

for you have fought with God and men

and have prevailed. (Gen 32:29)

Likewise, Ramban (Nachmanides) sees Jacob’s new name as the opposite of his old one:

Thus the name Ya’akov, an expression of guile or of deviousness, was changed to Israel [from the word sar (prince)] and they called him Yeshurun from the expression wholehearted ‘v’yashar’ (and upright).

Jacob’s new name, like his injury, proclaims the transforming encounter with the divine. Jacob experiences two encounters—one as a young man setting out on his journey with nothing, and one as a mature man surrounded by possessions and cares, dependents and responsibilities. Apparently, the transforming encounter is not only for the young and adventurous, but also for the middle-aged (or beyond) and established. Whether we are caught up in youthful self-absorption or in the complacency of mature age, only a touch from God will really change us.

“Turned into another man.” The earliest stories of Genesis hint at the hope of new birth that is central to the work of Messiah and the writings of the New Covenant millennia later. Jacob is the Everyman of Genesis, and his story reminds us that we all must be changed by a divine encounter to find our place in the renewed Creation. Our Messiah taught, “Amen, amen I tell you, unless one is born from above, he cannot see the kingdom of God” (John 3:3 TLV). And Jacob’s story reminds us that this new birth is not a one-time encounter, but one that is to be renewed throughout our lives.

Only an encounter with God can bring the transformation that prepares us for a lifetime of faithfulness. May we remain open to divine encounters that may await us, and may we embrace them as essential stages of our journey.

Adapted from Creation to Completion: A Guide to Life’s Journey from the Five Books of Moses, Messianic Jewish Publishers, 2006.