commentarY

“Friends, Romans, Countrymen, Lend Me Your . . . Year!”

In “Julius Caesar,” William Shakespeare takes the liberty of putting these words in Mark Anthony’s mouth: “Friends, Romans, countrymen; lend me your ears.” In the drama called life, Judaism takes the liberty of representing the Creator pleading: “Friends and Hebrew countrymen lend me your year.”

Shemini Atzeret–Simchat Torah 5784

By Dr Jeffrey Seif

Executive Director, Union of Messianic Jewish Congregations

In “Julius Caesar,” William Shakespeare takes the liberty of creatively putting the following words in Mark Anthony’s mouth: “Friends, Romans, countrymen; lend me your ears.” In the drama called life, Judaism takes the liberty of representing the Creator pleading with his creation: “Friends and Hebrew countrymen lend me your year.” Okay, I made it up. . . . Doesn’t exactly say that. Judaism does, however, beckon constituents to give Torah an ear for a year.

In the Diaspora, Shemini Atzeret (the eighth day of Sukkot) is followed by Simchat Torah (joy of the Torah), during which time the faithful focus upon and celebrate the Torah. Interestingly, God’s people are actually required to rejoice in the process—difficulties notwithstanding. Commenting on the mandate ve-samachta be-chagekha (that is, “you shall rejoice in your festival”), the Gaon of Vilna opined it was “the most difficult command in the Torah”—for obvious reasons. Harking to the command’s adherence amidst the turbulence of extremely trying times, Elie Wiesel commented that, even during the Holocaust, when it was “impossible to observe” the requirement to “rejoice,” Jews nevertheless “observed it” and rejoiced (Paul Steinberg, Celebrating the Jewish Year: The Fall Holidays [Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2007], 149). How does one do that amidst the turbulence of such trying times?

The notion of making oneself rejoice is hard to fathom. Seems one must possess a strong internal locus of control and have some object to focus upon besides one’s circumstances. Bounced around and affected as we too often are by external circumstances, we do well to focus on something beyond our circumstances. Focusing energies on something external helps stave off deleterious internal emotions that can plunge us into disorientation and despair. In Judaism, we are exhorted to make God’s Word the object of focus and adoration.

In Israel, Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah are combined into one day, with Simchat Torah marking both the end of the annual cycle of Torah reading (in Deuteronomy) and the restarting of the reading cycle for the new year (in Genesis). This public Torah reading tradition actually began in the Talmudic era (around the sixth century CE), with a pattern called the “Palestinian triennial.” Unlike our current one-year reading cycle, the triennial took three years to complete. Babylonian Jews, however, didn’t abide the lengthy practice followed in the land of Israel. By contrast, they divided the portions into the 50+ segments we call parshiyot—referencing segments of Masoretic texts in the Tanakh. In 1988, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement ratified and expanded the 50+ weekly reading segments, with their now being standard fare in Jewish communal experience.

Steady and disciplined exposure to biblical literature over time has an ameliorating impact on human experience. Mindful of that, we would do well to challenge ourselves—and others—to take seriously the demand to give God a concentrated year of Torah study. Were we to do so at the start of 5784, and keep a journal in the process of our so doing, we would discover that, in ways, we would be a different and better person by the time we get to 5785. Try it. Without detracting from the point I am trying to make here, it is worth noting the original intention of the holiday was different—though human betterment was indeed the object.

The maftir (concluding reading) for Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah is Numbers 29:35–30:1. The text recounts the mandate for the eighth day celebration. Recollecting the Torah isn’t mentioned. There, Israel is beckoned to cease from day-to-day labors and assemble before the Lord at the Mishkan / Beit HaMikdash (v. 35), bring special, seasonal sacrifices (vv. 36-38), and properly prepare those sacrifices along with those that are not season-specific (v. 39). The biblical tradition is tethered to bringing a Temple sacrifice; the synagogal tradition—noted above—is tethered to making a sacrifice: both are understood to pay great dividends.

New Covenant believers rightly understand Yeshua—the Word made flesh—to be the ultimate sacrifice. What too many believers miss, however, is the need to personally be sacrificial after receiving the ultimate sacrifice. For this, assembling proximate to the Word on a weekly basis is adjudged to be meritorious, as is paying ongoing attention to biblical revelation. Doing so elicits new and improved life forms around and within us.

On the Feast’s last day, Hoshana Raba, judgment decisions are said to have run their course. It is said: “During the festival of Sukkot the world as as a whole is judged for water, and for the blessings of the fruit of the crops” (Eliyahu Kitov, The Book of Our Heritage [Jerusalem / New York: Feldheim, 1978], 204; cf. 211-214). Interestingly, Yeshua’s word during Sukkot in John 7 seems to corroborate the point (see vv. 2, 8, 10 and 14). In vv. 37–38, John notes: “On the last and greatest day of the Feast, Yeshua stood up and cried out loudly, ‘If anyone is thirsty let him [or her] come to me and drink. Whoever believes in me, as the Scripture says, out of his [or her] innermost being will flow rivers of living water’” (TLV). To paraphrase, Yeshua said: “Hey—you want water and refreshment? Come to me!” He is the source of the water.

I heard him and came to him years ago. I know I need to keep on coming. . . . As we walk through 5784, let’s make frequenting our congregations a priority. Let’s take bringing forth the Torah seriously and let’s practice the implications of the words noted in it and expounded from it. It is my prayer that you as an individual, and we as a collection of congregations, be sufficiently watered and grow in the coming year. Give him your ear this year. You’ll be so glad you did.

Sukkot and Your Divine Purpose

With the arrival of the month of Tishrei, we enter the serious yet strangely joyous High Holy Day season. What starts with teshuvah/repentance at Rosh Hashana will be sealed on the judgment day of Yom Kippur. As if to give us all a divine break, we have five days from the close of Yom Kippur to the next major holiday: Sukkot.

This week we feature a special message for Sukkot by UMJC President, Rabbi Barney Kasdan.

This is truly an amazing time of year! With the arrival of the month of Tishrei, the Jewish world commemorates the serious yet strangely joyous High Holy Day season. What starts with teshuvah/repentance at Rosh Hashana will be sealed on the judgment day of Yom Kippur. As if to give us all a divine break, we have five days from the close of Yom Kippur to the next major holiday: Sukkot. Although called “the time of our rejoicing,” the Feast of Tabernacles is not without its serious side. Yes, there is the joy of building and dwelling in the sukkah at home and at shul. There are the festival meals with family and friends. And, of course, waving the lulav/palm branch to remind us of the physical blessings from our Heavenly Father.

Intermingled with the joy of the eight-day holiday, however, is a rather sober lesson in life. The scroll read for the festival is Kohelet/Ecclesiastes, which is a serious reminder of some of the realities of life. Solomon, the son of David, shares some of his vast experience with us every Sukkot. Interestingly, the rabbis note that Solomon penned his three famous works at crucial stages of his own life. Song of Songs was penned as a young man in courtship. Proverbs contains wisdom from his mid-life perspective. The final scroll, Kohelet, contains his reflections at the end of his days (Midrash Shir HaShirim 1:1). If that is the case, it is striking that the scroll of Kohelet starts with the exclamation “chavel chavelim/vanity of vanities!” Upon reflecting over his illustrious life, Solomon summarizes that it is essentially empty! What profit is a person’s work? Generations come and go. The sun rises and the wind blows, but what really changes? (Eccl 1:1–7). Simply put, there are so many things beyond our control. This could be very depressing or it could lead us to an entirely different direction. Now it becomes clearer why Megillat Kohelet is read every Sukkot. In the midst of the joy of the harvest and material blessings, we are reminded of the frailty of life. Who can control the twists and turns of life? The sukkah reminds us that there is a much bigger picture than even our current situation.

Additionally, Kohelet acknowledges that any innovations of mankind are rather meager in their importance. All things toil in weariness; the eye and the ear are never quite satisfied (1:8). Ultimately, “there is nothing new under the sun” (1:9). Our society is constantly looking for the latest gadget or phone upgrade to improve our existence. The incredible advance of technology impresses many. Yet, when a hurricane or pandemic hits, the world is suddenly shocked back into reality. For all our advances we are still so far from Paradise. How appropriate that we meditate on the lessons of Kohelet while we dwell in our simple sukkah. Whatever the blessings and benefits of our technologically advanced society, we are called to reflect on the simple realities of life. This time of year we are to get back to the wilderness experience of our ancestors. Although they had none of the modern conveniences we enjoy, were they less advanced than us today? Maybe there are forgotten truths that our generation needs to rediscover at this season of Sukkot.

Solomon goes on for chapters about the vanity of much of life. Yet, at the very end of the scroll, he summarizes his secret to living a fulfilled and purposeful life. “The end of the matter, all having been heard: fear God and keep His commandments” (12:13).

Even though life is fragile and unpredictable, there is a divine purpose. Despite the fact that all the busy activity of mankind is so meager, we are all here for a reason. Perhaps one of the best secrets of life is revealed at this time of year during Sukkot. Ultimately, all is vanity unless God is in the picture.

How fitting it is that it was on this festival that our Messiah gave a vital public message on the Temple Mount. “Now on the last day, the great day of the feast, Yeshua stood and cried out, saying, ‘If any man is thirsty, let him come to me and drink. He who believes in me, as the Scriptures said, from his innermost being shall flow rivers of living water’” (Yochanan/John 7:37–38). Messiah came to give us that personal connection to Hashem and to a life of meaning.

The sukkah, while reminding us of the vanity of this life, also holds forth the meaning of real life. May we all have a renewed perspective on our lives as we dwell in the sukkah for the eight days. Chag Sameach!

Moses the History Teacher Extraordinaire

It’s clear from the beginning of our parasha that Moses has a strong message to communicate. He begins by calling both Heaven and Earth as witnesses, and then goes on to say: “Remember the days of antiquity, understand the years across generations.”

Parashat Ha’azinu, Deuteronomy 32:1–52

Mary Haller, Tikvat Israel, Richmond, VA

Growing up in a small village in the Catskills in the 1960s and 1970, I found little to do when it came to entertainment or organized athletic events outside of school activities. So, school became a huge part of the day most of the year. I learned pretty quickly that I didn’t like sitting still and listening to what seemed like a constant flow of useless information. The elementary school years passed slowly until one day a new teacher burst onto the scene and the winds of change blew me into a new realm of appreciation for what was being taught. I will refer to this lively woman as the Storyteller. This teacher was the one to break through the fog of my inability to stay focused on learning.

The Storyteller made the information live. She presented every historic event with a face, a personality, a purpose assigned to it with words and excitement from her heart. The lessons went from bland and boring to colorful bits of information that began to jump off the pages of whatever textbook that was put before my eyes. My life was changed in the best way possible. The Storyteller introduced me to the value of history and the importance of learning about events as well as from all the people who lived before me. She encouraged us all to ask our parents and grandparents about our family histories. It was during this time that my love of history as a whole blossomed. I wouldn’t consider myself a serious student by any stretch of the imagination; I just fell in love with a good story that had a lesson for life.

The stories of the days of old and the people who lived through them caught my interest. Soon I realized that knowing about the past would affect the future. Reading about what people did and what happened as a result was something that needed to be shared for humans to continue to live life well. I had a new appreciation for not just school but also for all those who opened up the secrets of the universe through lessons, lectures, and simple life stories.

This brings me to Moses and our parasha, Ha’azinu, translated into English as “Listen.” A large part of this parasha is a song or poem. The section is significant for many reasons, one being it is thought to have been delivered to the people on the last day or one of the last days Moses lived. Every year when I read this passage known as the Song of Moses my appreciation for Moses as a servant leader grows.

It’s clear from the beginning of the parasha that Moses has a strong message to communicate. He begins by calling both Heaven and Earth as witnesses, and then goes on to say:

Remember the days of antiquity,

Understand the years across generations.

Ask your father and he will tell you,

Your elders and they will say to you. (Deut 32:7 TLV)

Clearly, Moses wanted to get the attention of his audience, much as my Storyteller teacher did. Moses wanted his audience to have an understanding of what those who went before them lived through. Having a firsthand understanding of how God “found them in the desert land,” Moses knew how God made them a people, how he chose them for his own, a people set apart from all others of humanity. Moses wanted all those listening to hear the message of God’s love and their importance to him. The parasha also reminds the listeners that their God graciously gave them a land that was fruitful, a place for them to live well and grow old. Moses didn’t stop there; he continued to warn the listeners of the pitfalls of having plenty and how their ancestors fell prey to laziness and turned their backs on their God after all his love and gifts of wonderful provisions for living.

We can feel the desperation and passion Moses must have experienced through the heartfelt poetic words we read as Moses speaks to his audience. Can you imagine the pain that Moses must have felt as he spoke the words to describe God “hiding his face” from them in Deuteronomy 32:20? Moses also reminded the people that in the end God would avenge the blood of his servants and be reconciled with his people and the land.

What makes this special in my understanding is how intimate Moses was with both God and the people. The parasha concludes with God’s instructions for Moses. He was to go to the summit of Mount Nebo, but only to catch a glimpse of the land for those who would come after him. Moses would only see the place he so desperately wanted all his audience of the day and his future audience to be able to enter into. Wow!

Much like my storyteller teacher, Moses used words to make the truth of history live for his audience. Moses knew his God and knew his audience, Moses recounted all that was necessary, not just for his listening audience as he was nearing his death, but for all those who would ask them the questions Moses wanted them to ask their predecessors. Generation to generation and beyond.

The words of Moses, a true servant leader, a man who lived a life of a gifted and extraordinary teacher, still live on today. I encourage each of you reading this to take some time to not just reflect on the parasha, but to go deeper. Like the people of Moses’ day, we too have much to be thankful for from our God. Like the people of Moses’ day we also have much to learn. Moses wanted his initial audience to listen and to pay close attention to all the words of Torah. By listening they would learn and see how to live out the goodness and glorify their God. As we know from Exodus, Moses knew firsthand the goodness and the glory of our God.

Moses said, “Please show me your glory.” And [God] said, “I will make all my goodness pass before you and will proclaim before you my name ‘The Lord.’” Exod 33:18–19 ESV

Moses knew what would happen if Torah was neglected and God’s ways ignored as stated in verses 16–21 of our portion. This message of “Listen,” Ha’azinu in Hebrew, is as valuable to us today as it was in the days of Moses. Yeshua, in the Besorah, reminds us of this: “Blessed rather are those who hear the word of God and keep it!” (Luke 11:28 ESV).

How we live our lives today will have an impact on the future of not only the planet but of all the people. May our lives impact the future for good as we live and worship our God in an honorable fashion. Shabbat Shalom!

It’s a New Year—Have a Blast!

Rosh Hashanah is Judaism’s Day of Judgment. Sound scary? Actually, it should be the most enjoyable day of your life. After all, it is your birthday. It’s everyone’s birthday! According to our tradition it is the world’s birthday!

Rosh Hashanah 5784

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Congregation Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

Rosh Hashanah is Judaism’s Day of Judgment. Sound scary? Actually, it should be the most enjoyable day of your life. After all, it is your birthday. It’s everyone’s birthday! According to our tradition it is the world’s birthday! So here are some ideas to help you have a blast (pun intended) this Rosh Hashanah.

God judges us because he loves us.

When my children were young, I would often use my “Daddy voice.” This was my stern voice accompanied by an equally stern look. It implied “cut it out or consider the consequences.” As my children got older, though, I incrementally allowed them more decision-making discretion knowing that the time would come when, as adults, they would have to make all of their own decisions.

For instance, we always ate Shabbat dinner together. But in High School I began to allow them to decide if they were going to exempt themselves from dinner to attend a special event. Generally, they made what I considered good and thoughtful decisions even if they were different than I would have made. At other times, and rarely, they used what I considered to be bad judgment though not dangerous choices. So, I would not retract the freedom I gave them. But that did not mean they did not get the Daddy voice and look when I asked if they really thought they had made a good choice. I know they found me “judgey” and would complain that I told them they had freedom but made them feel guilty for the decision they made.

Although my tone was somewhat strong, I believe my intent was loving. I wanted to give them guidance to help them live a good life then and into the future. I believe it was an act of love and I think they eventually experienced it as such.

Doesn’t every parent have a critical eye on their children? Isn’t every parent in some way or another constantly “judging” their children? We parents do this because we care so much about helping our children live meaningful and happy lives.

So too, the Creator of the universe; he “judges” us, not because he wants to punish us, but because he loves us and wants to make sure we live a great life. So, this year, starting today and as you continue on through Rosh Hashanah, feel the loving embrace of a Father who cares about you and only wants the very best for you, as it says in the Machzor, “For you are the King who desires life!”

Hear the shofar singing, “I love you—wake up and live!”

God is trying to get our attention. He’s calling out to each of us with the blast of the shofar. One sound of the shofar, the tekiah, and especially the tekiah gadolah is like a loud call—“Just want to make sure you’re listening.” Another tone, the teruah, is much softer. It touches a deeper, more vulnerable part of us. Hearing the shofar can be an awesome opportunity to feel God’s love. He’s calling out to us with urgent pleading tones, “Please wake up. Stop and think seriously about where you’re going in life. Please, think about what you really want out of life. Do it now while you still have life in you. All I want is that you have everything good.”

When you hear the shofar this year, listen closely and hear God’s love song being sung just to you.

Choose life.

Last week’s Torah portion, Nitsavim, concluded with the encouragement to “choose life!” (Deut 30:19). God can put the good life right in front of us and say, “Choose this,” but if we don’t have the clarity to want it, we’ll never take ownership of it.

The power of will is the only real power we have in this world; all else is an illusion. Rosh Hashanah is the time to learn how to use it.

In his seminal book True Virtue, Alasdair Macintyre tells a story from Polynesian folk lore, a kind of tropical midrash, if you will.

There once was a king who went out to the villages to visit the poor once every year. Approaching one very sad peasant, he said, “I will give you anything you want.” The peasant smiled and said, “I would like some grass to fix the hole in the roof of my hut.”

The king offered him anything, and all he asked for was some grass. How tragic! He could have asked for a mansion! But isn’t that our common cultural experience? The great King is offering us mansions and some settle for a little grass, or a drink, or a shopping spree. We choose to anesthetize ourselves rather than choosing to take the path of greater resistance but happier destiny.

On Rosh Hashanah when the King of the universe asks us, “What do you really want?” What will be our response? Will we be like the peasant in this story and ask for grass?

Everyone wants to have a great life. But if we don’t take responsibility to clarify for ourselves what the meaning of greatness is, we will likely conform to the values and standards of our society which seem to be more about seeking comfort than seeking greatness. What does a great life look like? Who are your models of success? Do you have a picture that you are completely satisfied with?

Ask yourself: What am I living for?

To live greatly, there is one question that we absolutely must ask: What am I living for? After all, how can I live if I don’t know what I’m living for? We get busy with being busy in order not to think about where our lives are ultimately headed. It’s a profound question and one that requires courage and great personal integrity.

On Rosh Hashanah God asks us to look in the mirror and judge ourselves. We engage the imposing specter of death so that we can ask ourselves, “What am I willing to live for?” This is a tremendous and awesome challenge. The Almighty is giving us life and we don’t know what to do with it. Life is too precious to waste. Rosh Hashanah is the time to clarify what we’re living for

Furthermore, how can I live the good life, if I don’t have my own definition of what “good’ means? There are many things that people call good such as love, creativity, power, kindness, knowledge, thinking, health, peace, relationship with God, wealth, and so on. This Rosh Hashanah explore this question: Of all the possibilities of what people deem good, what do I consider the greatest good? When we know what the greatest good is then we can truly live the “good life.” Why settle for second best?

Monitor your inner world.

One word for prayer in Hebrew is “l’hitpallel,” which most often is understood to mean judging. We pray to judge ourselves with divine guidance! Prayer can be an opportunity for self-discovery.

In 2007 a friend gave my wife two tickets to a Hannah Montana/Miley Cyrus “Best of both Worlds Concert” so she could take my then-7-year-old daughter. The interesting part of the story is that a famous recording artist was sitting in front of my wife and daughter since he was taking his pre-teen daughter and friends, and he was wearing ear plugs for the entire concert! Clear message!

I mention this because to read the Rosh Hashanah prayers without reflecting upon how they make us feel is like going to a concert wearing ear plugs. Use prayer as a tool for self-discovery and growth by listening to your feelings.

For example, there may be a moment in the prayer service that deeply moves you. It is crucial to hold on to the experience and try to understand what made that experience meaningful for you. If you can understand the meaning of that experience, you have discovered a precious insight that you can use for the rest of your life.

On the other hand, you may feel bored and disconnected. Again, it is crucial to ask, “What am I feeling and why am I feeling this way?” Understanding our emotional discomfort rather than counting the minutes until the service is over can open new pathways of self-understanding.

Prayer teaches us how to live consciously and intentionally. During the High Holidays don’t suffer through the prayers, rather let them be the diagnostic tools that they are meant to be and not mere volume knobs that control your emotions. Be honest. Be curious. This is not a day to tune out, but rather a day to tune in by listening to our feelings and learning from them.

In Judaism, every holiday is an opportunity for personal transformation. Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are called the High Holidays because they offer extra special opportunities for self-discovery and growth. They are not days of doom and gloom. This year, seize the opportunity, and yes, I am going to say this, have a blast!

Wrapping Ourselves in Messiah

Sos Asis – Hebrew for “rejoice greatly,” is the first phrase of this week’s haftarah and the title of the whole portion. We have endured, we have survived, we have overcome because of him, and now we are wrapped in his righteousness.

Sos Asis, Seventh Haftarah of Comfort, Isaiah 61:10–63:9

Suzy Linett, Devar Shalom, Ontario, CA

This week’s haftarah is the seventh and final reading of the Haftarot of Comfort, which are read from Tisha b’Av to Rosh Hashanah. The series takes us from a time of deepest sorrow and pain to the glory of the coronation of the King of Kings and coming to him in prayer and repentance for forgiveness and redemption. It is a cycle repeated in scripture from the original creation to the fall from Eden to redemption. It is a cycle seen in the history of Israel from glory to captivity to repentance and returning to the Lord and forgiveness, resulting in a return to glory.

The blueprint for all this was in creation itself, as chaos and darkness gave way to the separation of light and the provision of order by the Word of the Lord. We were separated from our Father and from each other, but now come together in him and with each other, culminating with Yom Kippur.

Why is this cycle repeated so many times? Those of you who have raised children, worked with children, or once were children, are familiar with phrases such as, “If I’ve told you once, I’ve told you a thousand times,” or “How many times do I need to repeat myself?” Our Heavenly Father says the same thing in his Word. He repeats patterns and lessons for us to read, re-read, and eventually learn and apply.

During my senior year of high school, the Jewish singer-songwriter Carole King released an album called Tapestry, containing the song by that name. In the story of that song, she speaks about the tapestry of life—how various threads, patterns, and pictures woven into a tapestry are not fully seen or understood until the entire project is complete. Then, and only then, can the relationships of heartbreak and joy, of gain and loss, of life and death themselves be comprehended and the beauty revealed.

This week’s haftarah portion is the final reading from Isaiah, a glorious transition from grief and mourning into joy, promise, and redemption. Isaiah compares, contrasts, and proclaims the glories of the Living Word with the promise of Messianic redemption through the pain and suffering endured by Israel and by Messiah himself. The threads of previous darkness and pain are woven into beauty and joy.

Although the haftarah begins with Isaiah 61:10, we miss significant prophecy unless we begin at verse 1. Verses 1–3 read:

The Ruach of Adonai Elohim is on me,

because Adonai has anointed me

to proclaim Good News to the poor.

He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted,

to proclaim liberty to the captives,

and the opening of the prison to those who are bound,

to proclaim the year of Adonai’s favor

and the day of our God’s vengeance,

to comfort all who mourn

to console those who mourn in Zion,

to give them beauty for ashes,

the oil of joy for mourning,

the garment of praise

for the spirit of heaviness,

that they might be called oaks of righteousness,

the planting of Adonai,

that He may be glorified.

What a promise of redemption and the coming Messiah! Indeed, Yeshua read this in the synagogue in Nazareth as stated in Luke 4:15–19, then proclaimed this prophecy had been fulfilled. The “garment of praise,” in which we are to wrap ourselves is Messiah himself!

As a result of this, we can join with Isaiah at the first verse of the actual haftarah portion, Isaiah 61:10:

I will rejoice greatly in Adonai.

My soul will be joyful in my God.

For He has clothed me with garments of salvation,

He has wrapped me in a robe of righteousness—

like a bridegroom wearing a priestly turban,

like a bride adorning herself with her jewels.

Sos Asis – Hebrew for “rejoice greatly,” is the first phrase of this verse and the title of the whole portion. We have endured, we have survived, we have overcome because of him, and now we are wrapped in his righteousness.

The transition from sorrow to complete joy requires a response. Isaiah 62 begins with not keeping silent—to continue to declare the Word of the Lord until Israel shines brightly and “Nations will see your righteousness, and all kings your glory” (verse 2). In the continuation of this portion, we are reminded of his promises.

Behold, Adonai has proclaimed

to the end of the earth:

Say to the Daughter of Zion,

“Behold, your salvation comes!

See, His reward is with Him,

and His recompense before Him.”

Then they will call them The Holy People,

The Redeemed of Adonai,

and you will be called, Sought Out,

A City Not Forsaken. (Isa 62:11–12)

Yom Teruah, the Feast of Trumpets known as Rosh Hashanah, coming just after this portion is read, is the day the King is crowned and takes his place on his throne and in our hearts and lives. The black threads of the tapestry, filled with darkness and pain, are woven together with gold, silver, and vivid life-giving colors. Life in Messiah is vibrant, it is alive, and we greatly rejoice – Sos asis!

Tisha b’Av, the day on which this special cycle of the Haftarot of Comfort begins, is known as the saddest day of the year. What is the happiest day? Some believe it is Tu b’Av, known as the “Jewish Valentine’s Day,” a celebration of human love. However, perhaps it is actually Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. We experience a cycle of joy at the coronation of the King, but then must, for the next ten days, cycle through consideration of our sins and our failures, and we must repent. On Yom Kippur we fast in somber contemplation. Yet, at the final call of this day, only ten days after the King is crowned, we can come before his throne. Not only are we allowed to come; we are encouraged and actually commanded to do so! The King of Glory invites us to come, calls us to come, to repent and enter into his presence with praise, with thanksgiving, and with great joy. We are received into the Divine Presence of Adonai Tzva’ot, the Lord of Hosts.

This is the day on which we are reunited with our Creator, with our Redeemer, with our King; and the day we are reunited with each other as members of his family. The tapestry is complete. We see the beauty of the picture painted for us and are awed by it. The cycle goes from the saddest to the greatest and happiest day. Sos asis!

Scripture references are from the TLV.

When the Way Seems Uncertain

Who am I? Where did I come from? Where am I going with my life? Is God with me or against me? I remember all too well the years when those pressing questions had no answer. And then the library workers at my university went on strike.

Parashat Ki Tavo, Deuteronomy 26:1–29:8

Ben Volman, UMJC Vice President

Who am I? Where did I come from? Where am I going with my life? Is God with me or against me? I remember all too well the years when those pressing questions had no answer. And then the library workers at my university went on strike.

I lived at home, and most assignments were done on campus in the study halls of multi-storied libraries. These were now closed. Then I read about a nearby college with a large study hall open to everyone. Somebody told me it was a seminary, but I didn’t know what that meant. Walking through the carved stone entrance, I was impressed by the high foyer and Oxford-style architecture. The oak-paneled study hall had nice large windows looking out on the campus.

Settling in behind a desk, I should have begun working, but I couldn’t. All around me were books on religion and the Bible. The people here studied about God and some of them must even believe that stuff. It was like being in church and I had a disturbing feeling: “I don’t belong here.” A few minutes later, I gathered up my books and fled.

At the time, I couldn’t explain what happened. I didn’t believe in God. But I knew that my life, my aspirations, and my thoughts, could never have held up under the spotlight of a righteous judge. It would take almost two years for my questions to lead me to the least likely place of all, peace with God through Messiah Yeshua. My decision at a campus meeting, surrounded by Jewish friends, changed everything. But I never thought of going back to that library.

As we transition through the stages of life, from school to career, to marriage, creating a family and beyond, those old questions still reappear. My prayers seek answers from God about where I’m going, especially when I face tough decisions and I have to ask myself: Am I asserting my own will or being authentic before God and genuinely faithful to his call?

In the ancient liturgy from the opening paragraphs of this week’s parashah, I hear this humbling instruction that teaches us the right attitude towards those questions. Although our ancient forebears were instructed to recite these words at Sukkot, the lessons are timeless.

“My ancestor was a nomad from Aram. He went down into Egypt few in number. . . . But the Egyptians treated us badly. . . . So we cried out to Adonai, the God of our ancestors . . . and Adonai brought us out of Egypt with a strong hand and a stretched-out arm. . . . Now he has brought us to this place and given us this land. . . . Therefore . . . I have now brought the first-fruits of the land which you, Adonai, have given me.” (Deut 26:5–10)

However much we’ve known of God’s grace and goodness, we will always remain the offspring of a wanderer, Ya’akov, who was found by God. But there is no mistaking who rescued us from bondage and gave us our land, and to whom the bikkurim, the firstfruits and first blessings of our land, belong. The words are simple yet gracious reminders of God’s ultimate sovereignty that must move into every area of our lives. And once we fully accept that truth into our being, we will “take joy in all the good that Adonai your God has given you” (Deut 26:11).

Even for believers in Yeshua, there are many harsh moments when it’s difficult to understand God’s sovereign will. For those times, Isaiah has given us his inspired visionary promise in this week’s haftarah of consolation. The prophet who called Hezekiah to defy the armies of Babylon leaves us this incredible legacy of hope in Isaiah 60:1.

Arise, shine [Jerusalem],

for your light has come,

the glory of Adonai

has risen over you.

The opening imperatives in the feminine form indicate that they are commands for Jerusalem. In the prophet’s own time, “thick darkness” may have hung over the city, but we are promised that the Lord’s kavod, the shining righteousness of his glorious presence, will surely break through. The nations will ultimately be drawn to the God of Israel reigning in all his righteous splendor (v. 3) and “then you will see and be radiant” (v. 5). It is an ultimate reassurance that in time, we will fully comprehend all that he has done and yet will do for us. No matter how overwhelming the situation, despite all the pain we’ve endured on this journey, his larger purpose for us and for all Israel will surely be revealed, as certainly as the dawn follows night.

All through the month of Elul, our congregations begin worship by blowing the shofar, calling God’s people to return, reflect and prepare themselves to gather in reverence for the coming High Holy Days. Unfortunately, that reverence is often ushered in under the shadow of judgment, the kind of judgment that I once feared so strongly. I think we’re often misled by depictions of a holy God measuring our sins against our mitzvot, our good deeds, as if our souls were in the hands of an exalted spiritual accountant.

My journey with Yeshua has given me a much different picture: a heavenly Father who is gracious and forgiving, who restores me when I fail and lifts me up when I’m stuck in doubt. I recall Yeshua’s words to the thief hanging next to him on a cross: “I will remember you—this day you will be with me in Gan Eden” (Luke 23:43), or to the woman caught in adultery: “Neither do I condemn you. Now go, and don’t sin any more” (John 8:11). Yeshua, who reached out to touch lepers and forgave tax-collectors urges us come closer, no matter how distant we feel from holiness: “I have not come to call the ‘righteous,’ but rather to call sinners” (Luke 5:32).

On Yom Kippur, in the moments before the cantor intones the opening notes of Kol Nidre, the rabbi addresses the congregation and speaks to those who fear in their hearts that that they aren’t worthy to join with God’s people: “By authority of the court on high and by authority of the court below, with the consent of the All-Present and with the consent of the congregation, we hereby permit prayer to go forward in the company of the transgressors.” We all have good reason to be penitent and yet every one of us is welcome into the presence of God. The brilliant 17th century Christian philosopher, Blaise Pascal, once said, there are only two kinds of people: saints who think they are sinners and sinners who think they are saints.

As a young believer with a B.A., I sensed the Lord calling me to get educated in the Word of God. For months I prayed about where to go to school, but none of the options gave me peace. On a lovely spring day, I went to hear the famous Hebrew Christian theologian Dr. Jakob Jocz at my old university. Later, I approached him to explain my dilemma and after we’d spoken awhile, his face brightened. He asked me if I was familiar with a seminary college on the other side of the campus. I mentioned that I did know of it, and he said those words that guided my life for the next several years and would provide the basis for many years of ministry to come: “Go there. They will take care of you.” A few minutes later, I was walking into the same building from which I’d fled only a few years before, and indeed, Jocz’s words proved true. Sometimes, I think God enjoys directing us with what we’d call a sense of humor.

Who am I? Where am I going? We never have all the answers. As Rav Sha’ul so humbly puts it: “It is not that I have already obtained it or already reached the goal — no, I keep pursuing it in the hope of taking hold of that for which the Messiah Yeshua took hold of me” (Phil 3:12). So, let us encourage one another to keep pressing on, even when we falter. After all, we follow in the steps of a wanderer, of slaves, of unpretentious workers in soil who considered it a privilege to bring their first fruits in a basket before the priest, and counted it all joy.

All Scripture citations are from the Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

Just Say Nothing

As we approach the midpoint of the Hebrew month of Elul, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur draw near, ushering in the Days of Awe. In about a month from now, as the sun sets, the reverberating melody and contemplative words of Kol Nidre will resonate through synagogues worldwide.

Parashat Ki Tetse, Deuteronomy 21:10 – 25:19

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

As we approach the midpoint of the Hebrew month of Elul, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur draw near, ushering in the Days of Awe, or Yamim Nora’im. In about a month from now, as the sun sets, the reverberating melody and contemplative words of Kol Nidre will resonate through synagogues worldwide. Kol Nidre, which translates to “all vows,” holds the peculiar function of preemptively absolving the binding nature of future promises for the upcoming year. At first glance, this prayer might be interpreted as either laziness or a spiritually questionable way to evade responsibility.

Interestingly, Kol Nidre seems to stand in direct contradiction to a proclamation found in this week’s Torah portion: “If you had refrained from making a vow, no guilt would have come upon you” (Deut 23:23). The words of the wise preacher Koheleth, traditionally attributed to King Solomon, echo this sentiment: “It is better that you do not make a vow than you make a vow and not fulfill it” (Eccl 5:4). Furthermore, the rabbis went as far as to emphatically warn against delaying vows, linking this procrastination to idolatry, unchastity, bloodshed, and slander (Leviticus Rabbah 37).

To reconcile this apparent contradiction, it’s essential to understand that not all vows are created equal in Judaism. There are distinct categories of vows, including oaths made as witnesses in court, purification oaths for debtors, personal obligations before God, and solemn affirmations to enhance credibility. However, none of these categories of vows are eradicated by mere ritual; the individual remains accountable for these vows legally, ethically, relationally, and religiously. The exception might be the personal aggrandizement type of vow, which could provide insight into the rationale behind Kol Nidre’s preemptive nullification of oaths.

But first, let’s delve into the origins and lore of Kol Nidre. Although its inception remains veiled in mystery, theories about its genesis abound. One prominent theory links the prayer’s wording to the predicament faced by Spanish Jews during the Inquisition in the 15th century.

The alternative of forced conversions to Christianity or death pushed many Jews to secretly practice Judaism at home. Kol Nidre could have emerged to nullify their coerced conversion vows before God. Most scholars, however, trace Kol Nidre back even further, possibly to the contracts of the Babylonian Jewish community during the 6th and 7th centuries. Despite differing origins, the consensus remains those vows made under duress, or the threat of death are not upheld by the Divine, and therefore, neither should we consider these binding.

This notion of vows made under extreme pressure dovetails with ethical considerations propagated by historical figures like Augustine and Emmanuel Kant. The Church Father Augustine (356–430 CE) argued, “Does he not speak most perversely who says that one person must die spiritually so that another may live? . . . Since, then, eternal life is lost by lying, a lie may never be told for the preservation of the temporal life of another.” Kant, an 18th century Christian philosopher, took a similar position. Both grappled with the moral dilemma of lying to safeguard lives.

In contrast, Judaism underscores that truth is a tangible interpersonal event, not just an abstract principle. The Torah illustrates instances where lying to preserve life is permissible. The rabbis understood the Torah to teach that for the preservation of life even God instructs the prophet Samuel to tell a lie (1 Sam 16:1–2). The rabbinic formula is “great is peace, because for its sake God altered what Samuel was to say.” This is applicable to those who concealed Jews during the Holocaust. In this case a false testimony is the same as a broken oath, but justifiable for the sake of pikuach nefesh, the preservation of life. Hence, Judaism honors those who lied to protect lives from the atrocities of the Nazis.

Moving beyond the quandaries of when vows should be nullified, it’s worth examining the most superfluous of oaths. This pertains to the category of vows made to enhance one’s credibility and status—a practice that both Yeshua and the rabbinic tradition scrutinized. Early rabbinic thought frowned upon invoking the Divine Name, adhering to the commandment, “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain” (Exod 20:7). This extends to avoiding actions that exploit divine authority for personal gain.

People began using circumlocutions like “the Merciful One” or “the Forbearing One” in their oaths, later resorting to phrases like “by heaven,” “by the Temple,” or “by the covenant.” Yeshua, however, disapproved of these formulations as well, as they still sought to circumvent divine sovereignty. His perspective concurred with the rabbinic stance against unnecessary vows.

Given these contexts, why, then, do we continue to proclaim Kol Nidre, nullifying all future vows from “this Yom Kippur until next Yom Kippur”? At face value, it seems paradoxical to accept the words of someone who has already absolved themselves of responsibility. In modern language, phrases like “I’m not lying” have become commonplace. Thus, a culture of swearing leads to the depreciation of trust in speech, dividing it into two categories: unconditionally true by Divine affirmation and others that appear relatively true or merely plausible. Nullifying all vows proactively admits the fragility of our commitment while elevating the sanctity of truth-telling. Those who grasp this concept tend to exercise caution in their speech; discretion is affirmed through silence, and actions resonate louder than words.

Just as the commandment against killing and slander emphasizes the sanctity of human life, and the preservation of marriage sanctifies the family as society’s fundamental unit, refraining from unnecessary swearing underscores truth as the bedrock of the Torah way of life—the foundation of the Kingdom of God.

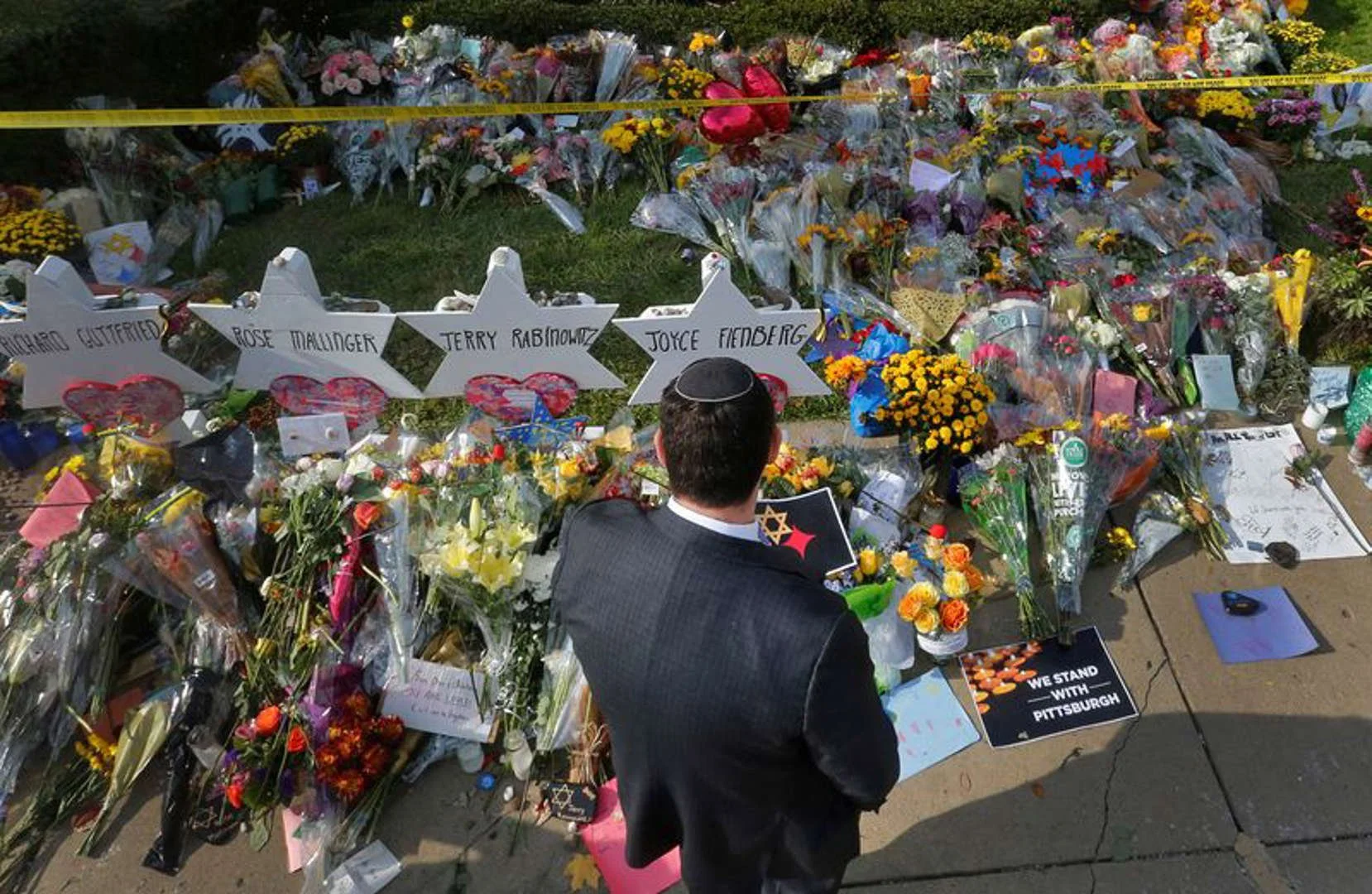

Justice, Not Vengeance

On October 27, 2018, Robert Bowers entered the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh shouting “All Jews must die!” He then proceeded to open fire. After the chaos had settled, eleven people had been murdered and six more critically wounded. It is the most violent antisemitic attack ever perpetrated on American soil.

Parashat Shoftim, Deuteronomy 16:18 - 21:9

Matthew Absolon, Beth Tfilah, Hollywood, FL

Justice, and only justice, you shall follow, that you may live and inherit the land that the Lord your God is giving you. (Deut 16:20)

The man who acts presumptuously by not obeying the priest who stands to minister there before the Lord your God, or the judge, that man shall die. So you shall purge the evil from Israel. ( Deut 17:12)

On October 27, 2018, Robert Bowers entered the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh shouting “All Jews must die!” He then proceeded to open fire. After the chaos had settled, eleven people had been murdered and six more critically wounded. It is the most violent antisemitic attack ever perpetrated on American soil.

Nearly five long years later on August 3, 2023, Bowers was formally sentenced to death.

Why did it take so long to exact justice? When we have the videos, the confessions, the 911 calls, the many, many eye-witnesses; why should vengeance be delayed for such an agonizingly long time? Why should the victims and the surviving families suffer so long to be denied their vengeance?

The answer is that we in America do not believe in vengeance, we believe in justice; and this belief finds its roots in the biblical world view of justice.

Rabbi Uri Regev in his paper, “Justice and Power: a Jewish Perspective” (https://www.berghahnjournals.com/view/journals/european-judaism/40/1/ej400113.xml) suggests that the Jewish fixation on justice starts at the very beginning of the Jewish story with our father Abraham. God commends Abraham in this way:

For I have chosen him, that he may command his children and his household after him to keep the way of the Lord by doing righteousness and justice, so that the Lord may bring to Abraham what he has promised him. (Gen 18:19)

Here the words “righteousness and justice” – tzedakah u’mishpat – stand as the cornerstone of Jewish law and indeed are the vehicle through which the Lord will “bring to Abraham what he has promised him.” Stated another way, Abraham will receive God’s promises “by doing righteousness and justice.”

Justice, however, can be a pesky thing. It is not convenient, and it stands as a barrier to our fits of anger, rage, and vengeance. Justice is often described as having “slow turning wheels” or, in the words of Martin Luther King Jr., “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Vengeance, however, requires no self-control; no moral discipline; no pause for thought. Vengeance amplifies its thirst for blood, when working in the collective of the mob. As we look down the annals of history, and reflect upon the social upheavals of the modern day, we see the great dangers of mob rule. Beckoning to the primitive and devilish ways that lurk in the deep recesses of each of our hearts, mob justice froths at the mouth in a sort of bestial trance, that defies reason, discipline, and self-control.

Our Lord was well accustomed to the mob. The mob tried to toss him off the cliff. He saved the woman caught in adultery from the mob. He was traded for the terrorist Barabbas by the approval of the mob.

Justice, in contrast, is a discipline. And moreover it cannot be explained outside a transcendent worldview. Without God, there is no framework to define justice. In fact, physical justice only has power when aligned with the spiritual view that man is made in the image of God (Gen 1:27; 9:6). As such man is endowed with free moral agency, and simultaneously endowed with infinite individual worth.

And so we see that justice at its core is not a system, or a person, or a socio-cultural phenomenon; justice is an outward expression of faith. It is an unwavering belief that man is created in the image of the Almighty God. As such we all contain the divine spark with its infinite and intrinsic value.

The neurotic hand of vengeance pays no attention to God’s claim upon every living soul and, when brandished in haste, vengeance leads to vengeance, and blood to more blood. Vengeance, like Justice, is a choice. It is a decision that we enter into for our own hurt.

Justice is a fruit that is cultivated in the individual heart as a moral decision that we must make, as an expression of God’s character and in humble submission to his divine claim as creator of mankind.

We Jews, along with our faithful friends, all breathed a mournful sigh of relief as we heard the verdict upon Robert Bowers that August night. But more than that, we decided to reject vengeance. Although we were killed, we burned with righteous anger, our hearts were broken with hurt; we did not give way to vengeance. We did not riot in the streets; we did not loot our neighbors; we did not burn down the city square.

No. Instead, with discipline and dignity, we upheld our spiritual duty by “doing righteousness and justice” that the promises of God may be visited upon the Children of Abraham.

In parallel to this, we submitted to God’s divine claim as creator by affording Robert Bowers the dignity of divine worth, through the exercise of justice, in contrast to the neurotic hand of vengeance. A dignity that he did not afford to us.

Justice is an act of spiritual discipline. It stands as the calming and stable hand of God, against the neurotic hand of vengeance. Justice is not found in the chants of the mob, or the passions of the grieving, or the swift bullet of the lawman; justice is found in the individual heart of every person who recognizes God’s sovereignty over his creation.

“Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” Amen.

Scripture references are from the English Standard Version (ESV).

Freer Than We Think

Our parasha begins with Moses speaking to the people of Israel in the plains across the Jordan river, offering us what is clearly a choice. Note the opening word, Re’eh, “See.” We are not to offhandedly choose one way or another by default, but are to really see this choice, to deeply encounter it . . . even if we may not have previously recognized it as a choice.

Parashat Re’eh, Deuteronomy 11:26-16:17

Dave Nichol, Ruach Israel, Needham, MA

“See, I am setting before you today a blessing and a curse—the blessing, if you listen to the mitzvot of Adonai your God that I am commanding you today, but the curse, if you do not listen to the mitzvot of Adonai your God, but turn from the way I am commanding you today, to go after other gods you have not known.” (Deut 11:26-28 TLV)

So our parasha begins, with Moses speaking to the people of Israel in the plains across the Jordan river, offering us what is clearly a choice. Note the opening word, Re’eh, “See.” We are not to offhandedly choose one way or another by default, but are to really see this choice, to deeply encounter it . . . even if we may not have previously recognized it as a choice.

The concept of free will has taken a beating in recent years. An article in The Atlantic announces, for example, that “there’s no such thing as free will,” based on a growing body of research in neuroscience and evolutionary biology. This reflects a growing trend—in both the hard sciences and philosophy—of skepticism in our ability to freely choose, well, anything (of course, there is lively debate on this issue, which I won’t get into here). On the other hand, by opening this speech with the command to see, Moses seems to be teaching us the opposite message: we often have more freedom than we think, choices that we don’t even realize are choices.

As the Atlantic article argues, some choices may be predetermined by our subconscious or by habituation—which clothes to wear, which route to take to work, and what overpriced coffee to order at Starbucks. But then there are others we may not recognize: when we choose to interpret someone else’s actions charitably or with cynicism, or choose frustration over forbearance when faced with a whining child. But these are choices as well, even if we don’t usually see them as such.

Put another way, breaking into that bag of chips, reacting in anger when someone cuts us off in traffic, or jumping to conclusions about another person based on a first impression, are all choices, but only if we are aware of the choice and put in the work to claw back the freedom to make them.

Danny Silk, in his insightful book, Keep Your Love On! Connection, Communication & Boundaries, sees exercising this freedom as an essential ingredient in relationships:

If you want to preserve relationships, then you must learn to respond instead of react to fear and pain. Responding does not come naturally. You can react without thinking, but you cannot respond without training your mind to think, your will to choose, and your body to obey. It is precisely this training that brings the best qualities in human beings—like courage, empathy, reason, compassion, justice, and generosity—to the surface. The ability to exercise these qualities and respond gives you other options besides disconnection in the face of relational pain.

If you have spent time around children (or perhaps have been one yourself), you have probably heard logic along the lines of, “He did this to me, so I had to respond this way.” Actually, you’ve probably heard adults doing this (and, dare I say, done it yourself): rationalizing a response by appealing to the circumstances or actions of someone else. Silk doesn’t let us get off that easily:

Powerful people are not slaves to their instincts. Powerful people can respond with love in the face of pain and fear. This “response-ability” is essential to building healthy relationships.

It is exactly the freedom to not respond in a predetermined way that makes us human. The ability to say, “Wow, that hurt. I’m angry. I feel a deep need to respond in kind, but I choose not to,” is the moral achievement par excellence in Judaism: overcoming the yetzer hara (evil inclination) and mastering the nefesh habehamit (animal soul). Yeshua exemplifies this, in that his ultimate act was to respond to hatred, violence, and injustice with lovingkindness and self-sacrifice. In exercising freedom to respond with generosity one could say he was the ultimate human. This explains why the besorah narratives never present Yeshua’s actions as predetermined, but show him having a choice (in the desert, in the garden) and choosing rightly.

It is commonly said that our emotions are outside our control, and to an extent that’s true. But if we dig into them a little deeper, we may find that our reactions are often rooted in deeply-ingrained beliefs that are either untrue or only partially true. This is why our reactions sometimes feel necessary in the moment, and silly a few hours later. Similarly, we are pretty good at giving ourselves (or our friends) the benefit of the doubt. Someone who cuts us off in traffic is a jerk or a bad driver; if we do it ourselves, it’s simply because we had to get over. Sorry!

The truth is that we make decisions almost every minute of the day, and most of them are about how to perceive, rather than what to do. Even how we see and interpret the world has an element of choice in it. As one of my favorite bumper stickers says, “Don’t believe everything you think!” Our tradition is quite aware, as the social sciences continue to confirm, that humans are anything but purely rational beings.

But, rather than being a downer, this message is deeply empowering. Moses teaches us that as we enter the land we have this power of choice within us. We are not mere puppets of our genetics, environment, or culture. Far from it! With a little work, even our previous choices can be repudiated and rectified through teshuva.

The challenge for us is one of awareness: to hold off before reacting, and to see the forces inside us that lead us to interpret something one way versus another. Thus may we be free to choose the blessing set before us.

Don’t Forget How to Remember

Remembering and not forgetting is a major issue in life as it is in this week’s parasha. In our very first verses we read. “Because you are listening to these rules, keeping and obeying them, Adonai your God will keep with you the covenant and mercy that he swore to your ancestors.”

Parashat Ekev, Deuteronomy 7:12–11:25

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann, Ahavat Zion Messianic Synagogue, Los Angeles

Remembering and not forgetting is a major issue in life, as it is in this week’s parasha.

In our very first verses we read. “Because you are listening to these rules, keeping and obeying them, Adonai your God will keep with you the covenant and mercy that he swore to your ancestors.” The kind of listening Moses highlights is the kind that results in appropriate action. If we are to apply God’s word to us, we must remember what it says. And this kind of remembering involves deep, attentive, and obedient attention.

Judaism is an auditory religion. That is why our core credo is, “Sh’ma Yisrael: Listen Israel,” and why the visual, idolatry, is foreign to our ethos. In ancient times, before the Gutenberg press, hearing was the faculty used to take in God’s Word. This is why we so frequently discover the Bible admonishing us to listen, rather than to read!

Life repeatedly teaches us to connect paying attention and remembering. When is the last time you couldn’t find your cell phone, your keys, or your glasses? And why was that? Wasn’t it because you failed to pay attention to where you put them. Yes it was!

Paying attention is essential to remembering. So is repetition, which is likely why our text repeatedly mentions remembering and not forgetting. The repetition is there to prevent us from forgetting and to enable us to remember.

In 8:2 we read, “You are to remember everything of the way in which Adonai led you these forty years in the desert, humbling and testing you in order to know what was in your heart — whether you would obey his mitzvot or not.” Moshe adds, “Think deeply about it” (v. 5). In 8:11 we read “be careful not to forget Adonai your God by not obeying his mitzvot, rulings and regulations that I am giving you today.” So we see here that remembering is an essential means toward obedience, which is what Hashem seeks from us. Being careful, that is, paying attention, is essential to success in remembering.

In verse 19, Moshe reminds us why all of this is important: “If you forget Adonai your God, follow other gods and serve and worship them, I am warning you in advance today that you will certainly perish.”

After all this emphasis on God telling us to remember, it is striking that our haftarah begins this way: “Tziyon says, ‘Adonai has abandoned me, Adonai has forgotten me.’ Can a woman forget her child at the breast, not show pity on the child from her womb? Even if these were to forget, I would not forget you. I have engraved you on the palms of my hands, your walls are always before me.”

Adonai is reporting that his people think he has forgotten them. This indictment against the Holy One is due to the downturn of their fortunes. But he is wrongly indicted. He remembers Israel even more than a woman remembers her child. Our walls are always before him.

For Jews, remembering is holy business. When we remember we bring the past into the present, such that it has the power to stand in judgment over us now.

The past is present in the event that we remember now, and our response to that memory is our response to the event itself and to the saving acts of God.

Each generation of Israel, living in a concrete situation within history, was challenged by God to obedient response through the medium of her tradition. Not a mere subjective reflection, but in the biblical category, a real event as a moment of redemptive time from the past initiated a genuine encounter in the present. (Brevard Childs, Memory and Tradition in Israel)

The events of Israel’s redemption were such significant realizations in history of divine redemptive intervention that, together with the rituals, rites, and commandments they entail, they have the authority to assess each successive generation of Israel, including ours. Our response to these events, rites, rituals, and obligations, is our response to God. And we are accountable. Even though we may wish to avoid this accountability, we cannot.

The Haggadah, echoing the Talmud, agrees. It reminds us, “In every generation a man is bound to regard himself as though he personally had gone forth from Egypt.” Torah tells us of Passover, “This will be a day for you to remember (v’haya hayom hazzeh lachem l’zikkaron)” (Exod 12:14).

The holy past is no mere collection of data to be recalled, but a continuing reality to be honored . . . or desecrated. As a zikkaron, a holy memorial, the redemption from Egypt is so authoritatively present with us at the seder, that a cavalier attitude toward the seder marks as “The Wicked Son,” unworthy of redemption, anyone who fails to accord it due respect. In this remembrance, the holy past is present with power, assessing our response.

That such past-evoking rituals have intrusive and unavoidable authority to judge our response is proven in Paul’s discussion of the Lord’s Table. In First Corinthians 11, he states that those who fail to discern the reality present among them in the ritual of remembrance, who drink the Lord’s cup and eat the bread in an unworthy manner, desecrate the body and blood of the Lord and eat and drink judgment upon themselves. He makes this point unambiguous when he states, “This is why many among you are weak and sick, and some have died” (1 Cor 11:23–31).

Because of this numinous power of holy remembrance, honoring the holy Jewish past and the holy Jewish future as re-presented in the liturgy, ritual, and calendar of our people must become a lived reality in our movement. Our only other option is to dishonor God and to trifle with his saving acts. I think it no exaggeration to say that failure to properly honor our holy past is just as truly an act of desecration as was the failure of the Corinthians to honor the body and blood of Messiah present in their midst in the bread and the wine.

Don’t forget how to remember. It’s serious business.

Scripture references are from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).