commentarY

You Know, You Are Also Right

Probably about once a month, I will think about this famous scene in “Fiddler on the Roof.” Tevye is observing a conversation between two men, arguing about whether we need to read the newspaper and be aware of outside events or not. He agrees with each one in turn by saying “You’re right.”

Parashat Vayishlach, Genesis 32:4-36:43

Rabbi David Wein, Tikvat Israel, Richmond, VA

Probably about once a month, I will think about this famous scene in “Fiddler on the Roof.” Tevye is observing a conversation between two men, arguing about whether we need to read the newspaper and be aware of outside events or not. He agrees with each one in turn by saying “You’re right.” Then, another man says, “Wait a minute, he is right and he is right? How can they both be right?” To which Tevye responds, “You know, you are also right.”

What I love about this is that it’s brilliant diplomacy and wisdom all at once. Some tensions in our theology and our lives are never fully resolved. These tensions are apparently opposing truths which are both correct. If you are married, you may have experienced this phenomenon. Now, I’m sure you are convinced in your mind that your way of doing the dishes is the correct way, but there may be something to the other person’s perspective that’s worth hearing out. The key to resolving this kind of impasse is to draw out the other person’s narrative, so that they feel seen, understood, and valued. The goal is not necessarily to be right. However, the only way that you could both be right is if you both are understood and valued. Easier said than done, but it is possible.

Pastor Peter Steinke (a disciple of Rabbi Edwin Friedman) describes the tension within a need we have in all our relationships: to be connected and to be an individual. In other words, we long to have loving affirmation and encouragement with one another and at the same time to be able to define ourselves rooted in the affirmation and encouragement of God. We seek neither to placate the other person for fear of rejection, nor to isolate from the other person for fear of conflict. We make decisions both out of compassion on the one hand, and out of a sense of values based on Scripture on the other. If we can learn to balance these two over time, we can mitigate conflict and partner with God for the repairing of the earth (Tikkun Olam). “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God” (Yeshua the Messiah in Matthew 5:9). I’m waiting for the day that I will meet my Maker and he will say, “You know, David, as a peacemaker, you were also right.” Dream big, eh?

And this brings us to this week’s parasha, featuring our dubious hero (or maybe anti-hero), Jacob. Having finagled both the birthright of the firstborn son and the blessing meant for Esau, Jacob is now scrambling and lowering himself to prepare to see his brother after twenty years. He sends gifts, he refers to Esau as “my lord” and himself as “your servant,” and he divides his camp so that if Esau destroys half of his family out of revenge, at least he has something left.

We know Jacob. We know he uses deception and manipulation, but we know he values the blessings of God. We know he is a heel grabber, but that doesn’t just make him an annoying noodge--he is also tenacious and resilient. Jacob acknowledges in this parasha that he is blessed beyond what he deserves, and aren’t we all? Are we really any better than our conflicted ancestor, the namesake of Israel? Listen to his prayer in preparation to meet his brother:

“O God of my father Abraham, and God of my father Isaac, Adonai, who said to me, ‘Return to your land and to your relatives and I will do good with you.’ I am unworthy of all the proofs of mercy and of all the dependability that You have shown to your servant. For with only my staff I crossed over this Jordan, and now I’ve become two camps. Deliver me, please, from my brother’s hand, from Esau’s hand, for I’m afraid of him that he’ll come and strike me—the mothers with the children. You Yourself said, ‘I will most certainly do good with you, and will make your seed like the sand of the sea that cannot be counted because of its abundance.’” (Gen 32:10-13, TLV)

It’s God’s faithfulness vs. Jacob’s character flaws. Who wins that wrestling match? So we ask, “Is Jacob actually repentant?” Perhaps only partially, but he is both humbled and bold. “Lord, you said you would do good to me and to my descendants, and even though I’m afraid of my brother, I trust you.”

Jacob’s story isn’t really just about Jacob. It’s about God. Many rabbis have tried to massage this story to make Jacob more acceptable and Esau more unacceptable. But we don’t need to apologize for Jacob. We are also acceptable only because of God’s sovereign love, and not because we are always shining examples “worthy” of that love. But God does accept Jacob, and he does accept us. God is known in the Scriptures as the God of Israel, and even sometimes as the God of Jacob. The Lord stakes his name, his reputation, his shem, on Jacob and his imperfect descendants, because God cannot be unfaithful to himself.

The Lord of armies is with us;

The God of Jacob is our stronghold. Selah. (Psalm 46:7 NASB)

Jacob wrestles with God, with his brother, and ultimately with himself. He “wins” the fight, but comes out limping. Formerly the blessing-grabber, he is now the longsuffering, blessing-holder--from Ya’akov to Yisrael. And us? We wrestle with Jacob in all his glorious flaws--we scratch our heads at him and say like that great Jewish sage, Jerry Seinfeld: “Really?!” But Jacob is us. The text is a mirror, and we are full of contradictions, truths apparently opposed to one another inside us like a kaleidoscope. But we’re still here. We’re still loved by God, and we’re holding on to the blessings, and more so clinging to the Blessing-Giver.

Keep going, keep loving, keep wrestling it out. The truth is, we’re all in process, and the process is messy and takes time. Give yourself grace. Progress, not perfection, as a friend reminded me recently. After all, God loved and was faithful to a rough-around-the-edges guy like Jacob to bring to bear his covenant promise, and to do good to him and his descendants, the Jewish people.

The conflicts between Jacob and Esau (Israel and Edom), Jacob and God, and Jacob and himself are a sample of all conflicts we experience. Messiah Yeshua reconciles us back to God, back to each other, and back together within ourselves.

For it pleased God to have his full being live in his Son and through his Son to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace through him, through having his Son shed his blood by being executed on a stake (Col. 1:19-20, CJB).

The gospel brings peace amongst the opposing forces within us and among us. So, the way to be right isn’t always to be correct. We are also right because we are made right, made cleansed, having received a right-ness as a gift through Messiah Yeshua. In that sense, you know, you are also right!

The Twelve Tribes and Beyond

Our tribal history contains the classic elements of being chosen, having a special legacy, and being different from (and perhaps superior to) the Other. But in typical fashion for the Torah, the account of tribal origins points beyond the usual motifs to hint at hope and transformation to come.

Parashat Vayetse, Genesis 28:10–32:3

Rabbi Russ Resnik

In the Jewish community, we sometimes identify ourselves as MOTs, Members of the Tribe. It’s a bit whimsical, but it’s also a bit problematic in our current social-political climate, where “tribalism” is not a happy term. Our Torah reading last week introduced Jacob, the father of the Twelve Tribes of which all Jews are members. The tribal history continues in this week’s parasha and contains the classic elements of being chosen, having a special legacy, and being different from (and perhaps superior to) the Other. But in typical fashion, the Torah’s account of tribal origins points beyond the usual motifs to hint at hope and transformation to come.

We saw last week how our forefather Jacob was caught up from before birth in a struggle with his brother Esau, a struggle that sounds pretty tribal from the outset. Their parents, Isaac and Rebekah, struggle with barrenness through the first twenty years of their marriage. Finally, Isaac prays for Rebekah and she becomes pregnant . . . with twins!

But the children struggled with one another inside her, and she said, “If it’s like this, why is this happening to me?” So she went to inquire of Adonai. Adonai said to her:

“Two nations are in your womb,

and two peoples from your body

will be separated.

One people will be stronger

than the other people,

but the older will serve the younger.” (Gen 25:22–23)

The younger is Jacob, of course, and his early years are marked by strife and competition with Esau, from whom Jacob gains both his birthright and his blessing (belonging to Esau as the first born, since he emerged from the womb just ahead of Jacob). The struggle with Esau becomes so intense that Jacob has to flee the land of promise in fear of his life, and this week’s parasha opens as Jacob begins his journey into exile. He spends the night in “a certain place,” where he dreams of a ladder or ramp joining heaven and earth, with the Lord appearing and saying to him,

I am Adonai, the God of your father Abraham and the God of Isaac. The land on which you lie, I will give it to you and to your seed. Your seed will be as the dust of the land, and you will burst forth to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south. And in you all the families of the earth will be blessed—and in your seed. (Gen 28:13–14)

Jacob is the founder of a tribe, but it’s a tribal story that points beyond itself, because Jacob’s seed, in line with the prophetic words given earlier to grandfather Abraham (Gen 12:3), will be the source of blessing for all the families of the earth. This Torah narrative is tribal, but universal as well, pointing to a future of blessing for all the earth’s inhabitants.

But there’s a more immediate and less noticeable thread in the tapestry of Jacob’s tribal story that also hints at a reality beyond tribalism—the humanity of Esau, the son not chosen. When Esau discovers in last week’s parasha that Jacob has received his father’s blessing instead of him, he begs Isaac, “‘Haven’t you saved a blessing for me? . . . Do you just have one blessing, my father? Bless me too, my father!’ And Esau lifted up his voice and wept” (Gen 27:36, 38). Esau is impulsive and unstable. He loses his birthright because he despises it (Gen 25:34). After Jacob diverts his blessing to himself, Esau vows to kill him, thus triggering Jacob’s twenty-year exile, which begins in this week’s parasha (Gen 27:41–45). But for all that, the Torah portrays his sorrow over losing the blessing with compassion. Esau is not the tribal Other, but a fully-formed human character, flawed but evoking our generosity.

Throughout Jacob’s trying twenty-year exile from the land of promise, Esau isn’t mentioned at all. Again, our founding narrative refrains from the sort of belligerence and chest-thumping we might expect in a tribal tale. Esau reappears only as the exile is about to end, coming to meet Jacob with what looks like a war party of 400 men. But when the two finally meet, the Torah again portrays Esau with generosity and deep emotional connection.

When Esau saw Jacob coming toward him, he “ran to meet him, hugged him, fell on his neck and kissed him—and they wept” (Gen 33:4). Then he tried to refuse Jacob’s gifts of tribute, saying, “I have plenty! O my brother, do keep all that belongs to you” (Gen 33:9), and offered to escort Jacob and his whole household back into the land of promise.

Jacob declines to go with Esau, which some of our sages commend as a wise move, because of Esau’s emotional instability. It may seem better to part company while the feelings are good and Jacob is safe. But finally the two do reunite, at the death of Isaac, to mourn their father together. “Then Isaac breathed his last and died, and was gathered to his peoples, old and full of days. So his sons Esau and Jacob buried him” (Gen 35:29). Tellingly, in this final scene, Esau is named first, before Jacob. This reunion, however brief, reminds us of the equally significant reunion of Isaac and Ishmael at the death of Abraham (Gen 25:8–9).

The Torah insists on weaving the bright thread of our shared humanity into the complex tapestry of Jacob’s tribal origins.

Last week, I had the privilege of joining over 200,000 Members of the Tribe and supporters in the March for Israel, calling for release of the Hamas hostages and opposing the current surge in antisemitism. As I was swept along with the crowd toward the U.S. Capitol, I thought of the psalmists’ words about joining the multitudes, the tribes going up to worship Hashem (Psa 42:5; 122:4). We were there to protest and advocate, not worship in the usual sense, but the feeling of tribal assembly was overwhelming. One of the speakers, historian Deborah Lipstadt, provided a healthy balance, amazingly linked to the current Torah readings: “Do not sink to the level of those who harass you, but do not cower. Jews are strongest at their broken places.”

Jews are strongest at their broken places, like our father Jacob, who returned from exile lame and leaning on his staff to be reunited with his brother-adversary Esau. Jacob is a model for his descendants. Our journey, like his, is one of vulnerability and struggle, but also one in which we are to recognize the humanity of the Other and thereby keep hope alive.

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

Keep Digging Those Wells

The Jewish spirit is a productive spirit. It works for the future and believes against all hope that the desert can indeed bloom. The Jewish spirit believes that through the diligent application of hard work in the land where we sojourn, we will not just survive, but we will thrive.

Parashat Tol’dot, Genesis 25:19-28:9

Matthew Absolon, Congregation Beth T'filah, Hollywood, FL

The reading for this week’s drash is a little longer than normal, as I want to capture the narrative laid out during this time of Isaac’s life. The Torah contrasts the values of Abraham and Isaac and, by extension, the values of God's chosen people, with the values of the heathen nations wherein they resided.

And Isaac sowed in that land and reaped in the same year a hundredfold. The Lord blessed him, and the man became rich, and gained more and more until he became very wealthy. He had possessions of flocks and herds and many servants, so that the Philistines envied him. (Now the Philistines had stopped and filled with earth all the wells that his father’s servants had dug in the days of Abraham his father.)

And Isaac dug again the wells of water that had been dug in the days of Abraham his father, which the Philistines had stopped after the death of Abraham. And he gave them the names that his father had given them. But when Isaac’s servants dug in the valley and found there a well of spring water, the herdsmen of Gerar quarreled with Isaac’s herdsmen, saying, “The water is ours.” So he called the name of the well Esek, because they contended with him. Then they dug another well, and they quarreled over that also, so he called its name Sitnah. And he moved from there and dug another well, and they did not quarrel over it. So he called its name Rehoboth, saying, “For now the Lord has made room for us, and we shall be fruitful in the land.”

23 From there he went up to Beersheba.

32 That same day Isaac’s servants came and told him about the well that they had dug and said to him, “We have found water.” He called it Shibah; therefore the name of the city is Beersheba to this day. Gen 26:12-33

Abraham was a well-digger. And he taught his son Isaac to be a well-digger. The key to surviving in the land of Israel is water. Water was the key 3000 years ago, and water is still the key to this day. The location, extraction, and efficient usage of water means the difference between life and death in our homeland. In modern times Israel has become a world leader in its innovative technologies surrounding the efficient usage of water. Israel has partnered with countries in desert regions of Africa, showing them how to turn dry, arid, and unproductive land into gardens and fields full of crops.

So important is water in the Middle East that the decisive battle for control of the Middle East during World War I was over the well of Beersheba, a well that was first dug in this week’s parasha. When the allied forces led by the Australian Light-Horsemen captured the well of Beersheba, they turned the tide of the war against the Ottoman Turks in World War 1.

I have an emotional response to this history because I grew up in rural Australia. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth. I have been present when wells have been dug and water comes gushing forth from the ground below. From the first sign of wet soil to the final gushing of water to the surface, it is mirrored by the welling emotions of hope, exuberance, and finally relief. Relief because our efforts were not in vain. Relief because now we, our loved ones, and our livestock will not starve. Relief because there is hope for a future.

Isaac was a well-digger. Isaac believed in productivity. Isaac was a bringer of hope. Isaac believed in the future.

The Philistines, however, were well-destroyers. In the name of survival, it is understandable that one might capture a well and steal its life-giving water to provide for one’s own tribe. But to fill in a well and to destroy it, thus increasing the likelihood of malnutrition and starvation to one’s own family and tribe, requires a fiendish and perverse ethic. It is one evil to steal wealth. It is another level of evil to simply destroy it.

In Israel, water is wealth. So why did the Philistines fill in the wells?

He had possessions of flocks and herds and many servants, so that the Philistines envied him. Gen 26:14

The Hebrew word for “envied” in this text is not a passive emotion. It is a verb. It describes an envy that turns to anger. The Philistines were angry with Isaac, because Isaac was productive and successful. They were angry with Isaac, because Isaac believed in a future. They were angry with Isaac, because Isaac revived the land, and brought hope to its inhabitants.

There is a lesson to be learned in this interaction, and it is this: There exists a spirit which, against all sound logic, prefers jealousy over cooperation; anger over humility; destruction over productivity. It is a dark and devilish spirit.

The 19th century rabbi Ha’amek Davar, drawing from Midrash Rabbah, explains that this verse is prophetic, foreshadowing the future exiles when Jewish residency rights were restricted, and our success will engender the jealousy of the nations leading to our continual banishment. Moreover, it is not just anti-Jewish to be jealous of success, it is anti-God. To hate wealth and productivity and material success is a form of cultural nihilism that steals the bread from the future generation of children not yet born. To hate productivity is to hate life itself.

But the Jewish spirit is a productive spirit. The Jewish spirit works for the future and believes against all hope that the desert can indeed bloom. The Jewish spirit believes that through the diligent application of hard work in the land where we sojourn, we will not just survive, but we will thrive.

Our Lord Yeshua speaks of this spirit of productivity in expansive terms in the Parable of the Talents. The wicked and unproductive servant describes the Master, allegorically speaking of God, in this way: “Master, I knew you to be a hard man, reaping where you did not sow, and gathering where you scattered no seed.” The Master berates the unproductive servant and says these difficult words: “For to everyone who has will more be given, and he will have an abundance. But from the one who has not, even what he has will be taken away” (Matt 25:29). In other words, the good servant is one who is working, diligent, and productive. Just like Abraham. Just like Isaac.

This is our spiritual heritage. We belong to a long line of hopeful and ambitious men and women who under Gods providential hand have been well-diggers. And just like the Philistines in this parasha, there are always those who hate us precisely because of our productivity.

We must never forget that our productivity is inseparably tied to our holy calling. Our productivity is inseparably tied to the spirit of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Our productivity is inseparably tied the nature of our heavenly Father.

The challenge that we face in Israel today bears the hallmarks of this ancient conflict between Isaac and the Philistines of his day. We Jews are dedicated to digging wells, sowing crops, and living a productive life. Hamas is dedicated to destroying wells, burning crops, and disseminating death. The more we are productive, the more they hate us for it, even if they are the recipients of our abundance.

As I close, I want to leave a note of exhortation to the UMJC community. Be like your forefathers Abraham and Isaac. Dig wells. Plant crops. Work with all diligence. Resist the haters. Believe in the future. Hold fast to hope. Don’t just survive. Thrive!

Taking the Long View

This week’s parasha brings us the account of the very first land purchase in the Land of Promise. Seeking a place to bury his wife, Sarah, Abraham approaches a local landowner to purchase the cave of Machpelah, which was on his property.

Machpelah, Tomb of the Patriarchs, in Hebron

Parashat Chayei Sarah, Genesis 23:1–25:18

Chaim Dauermann, Brooklyn, NY

For the Jewish people, Eretz Yisrael is never far out of mind. This has been especially true in the month since the October 7th massacre perpetrated by Hamas, which took the lives of 1400 people in Israel and led to over 200 hostages being brought into Gaza.

As in past times of conflict in Israel, the validity of Jewish presence in the Land has become a matter of uncomfortable public debate. Many of Israel’s latest detractors may be unaware, or otherwise unwilling to consider, that the Zionist movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was typified not by the “illegal” land grabs they might imagine, but by something far more mundane: land purchases made in full accordance with the law. And it was on the foundation of these land purchases that the Jewish diaspora was regathered in the Land and, eventually the State of Israel was formed.

This week’s parasha brings us the account of the very first land purchase in the Land of Promise. As the portion begins, Sarah has died in Kiriath-arba—or Hebron—near the Oaks of Mamre, where Abraham has been dwelling for some time. Seeking a place to bury his wife, he approaches a local landowner to purchase the cave of Machpelah, which was on his property.

And Ephron the Hittite answered Abraham in the ears of the sons of Heth, all those who enter the gate of his city, saying, “No, my lord, listen to me. The field—I hereby give it to you. Also the cave that is in it—I hereby give it to you. In the eyes of the sons of my people, I hereby give it to you. Bury your dead one.” (Gen 23:10b–11)

Abraham, however, insists upon paying for the field and cave. And when Ephron quotes him a price of 400 shekels, he does not hesitate or bargain. There has been much debate among commentators as to whether this was a good deal. It’s ultimately unclear. But, high price or not, a key thing to note is Abraham’s insistence on paying the full price. By avoiding taking the Machpelah cave and field as a gift, or even at a discount, Abraham helped insure himself against dispute, such as in the event of Ephron’s death. In doing so, he secured a site not only for Sarah’s burial, but also for his own, and for Isaac and Jacob’s after him.

Abraham had his eye fixed on the future. God had already revealed to him that the promise of the Land was a promise deferred:

Then He said to Abram, “Know for certain that your seed will be strangers in a land that is not theirs, and they will be enslaved and oppressed 400 years. . . . Then in the fourth generation they will return here.” (Gen 15:13, 16a)

Abraham knew his own days were numbered. He made his land purchase while looking to a promise he himself would not see fulfilled. He was thinking of the not-yet.

Jewish tradition sees the Machpelah purchase as quite consequential, and many traditions surround its history and meaning. One suggests that the purchase was made in order to inspire the future inheritors of the Land.

The interpretation of Rava is recorded, who states, “It teaches that Caleb separated himself from the counsel of the spies, and went and threw himself upon the graves of the patriarchs. My fathers, cried he, pray for me, that I may escape the counsel of the spies.” (Sotah 34b)

In this telling, the Machpelah site plays a key role in Caleb’s experience as one of the twelve spies to go scout out the land (Num 13). Perhaps it was the knowledge of this ancestral possession that inspired his confidence concerning the Land, even as ten other spies ultimately failed to believe it could be taken.

Abraham’s purchase is not the only instance in Scripture where land is bought as a foundation for promises with a deferred fulfillment. The prophet Jeremiah records that, even as Jerusalem was under siege by the Babylonians—with its destruction and the Captivity imminent—God commanded him to purchase a field in Anathoth, a place only a short distance north of the city. When Jeremiah inquired of the Lord as to why he would command such a purchase at this time, he replied, “Just as I have brought all this great evil on this people, so I will bring on them all the good that I have promised them. So fields will be bought in this land . . . because I will bring them back from exile” (Jer 32:42–43a, 44b).

Elsewhere, we read of King David purchasing (for full price) the threshing floor of Ornan, a place where one day the Temple would stand, although David would not live to see it.

In hindsight, there is a bit of an irony here. Today, the Jewish people are in the Land after the miraculous restorations of 1948 and 1967. All three of these locations, however—Hebron, the site of the ancient city of Anathoth, and the Temple Mount—are currently outside of Israeli control. Just as Abraham, Jeremiah, and David all made their purchases with a long view toward the fulfillment of God’s plans, today the Jewish people continue in a similar not-yet. And as believers in Yeshua, our sense of expectation and eager longing for fulfillment have a scope that is similarly broad.

The author of Hebrews tells us that Abraham has a longer vision than we might understand from the text in Genesis alone. He says that Abraham was “waiting for the city that had foundations, whose architect and builder is God” (Heb 11:10). He later calls this, “The city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem” (12:22). John the Apostle records for us that when Yeshua was preparing his disciples for his departure, he told them he was going to prepare a place where they—and by extension, we—can be with him, a place with “many dwelling places” (John 14:2–3). Later, in Revelation, John gives a glimpse of a “city to come,” saying, “I also saw the holy city—the New Jerusalem—coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband” (Rev 21:2). As for when John’s vision will come to fruition, only God knows. But the witness of Scripture gives us faith in its coming, even if its timing may transcend our earthly lives.

God’s relationship with us has always been built on his faithful nature. He keeps his promises. In times of uncertainty, even (or especially) when we cannot see God’s promise in full, let us, like Abraham, take a long view of God’s redemptive plans. Let us strive to be a Caleb among unfaithful spies.

Meanwhile, let us also pray unceasingly for every hostage’s safe return from Gaza, and for a new and lasting peace in the Land.

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

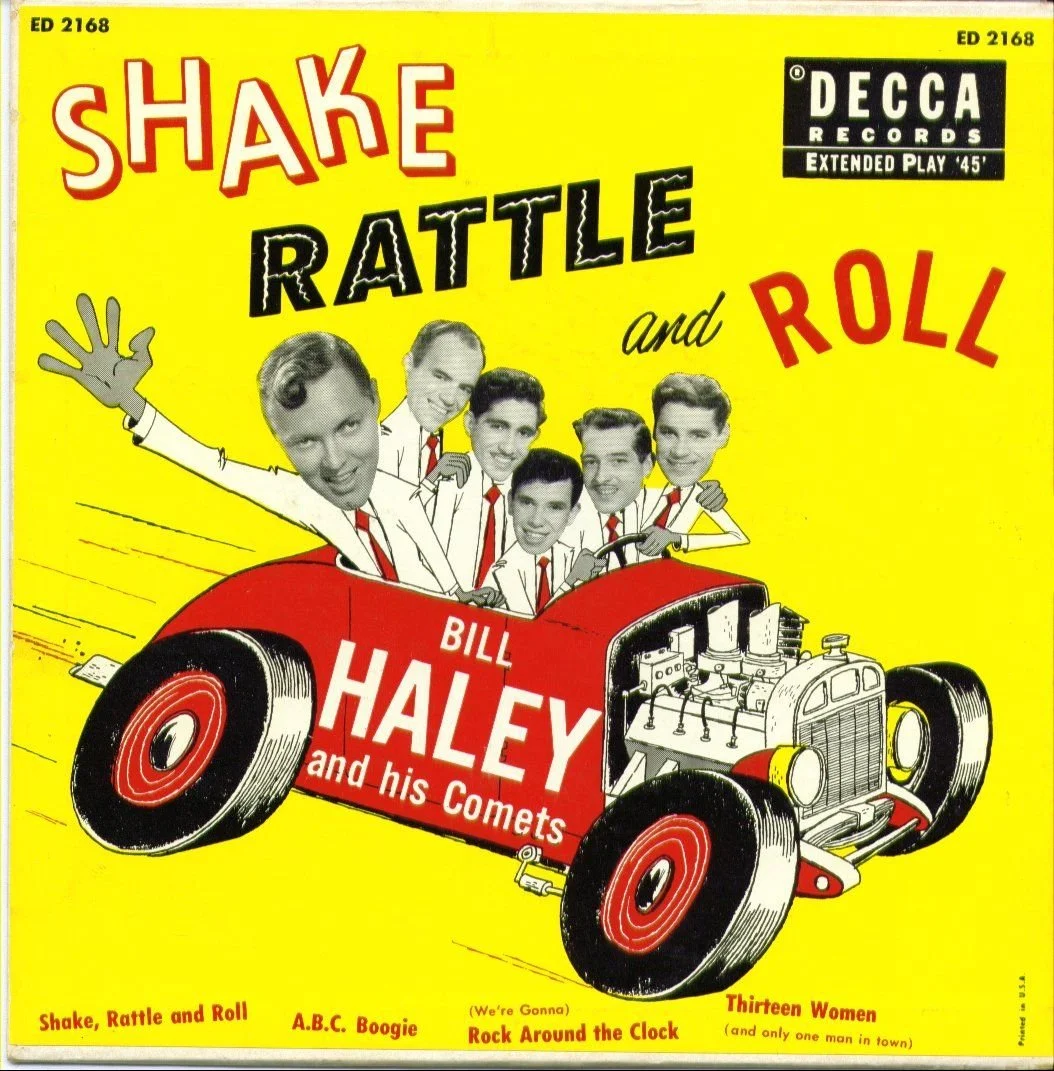

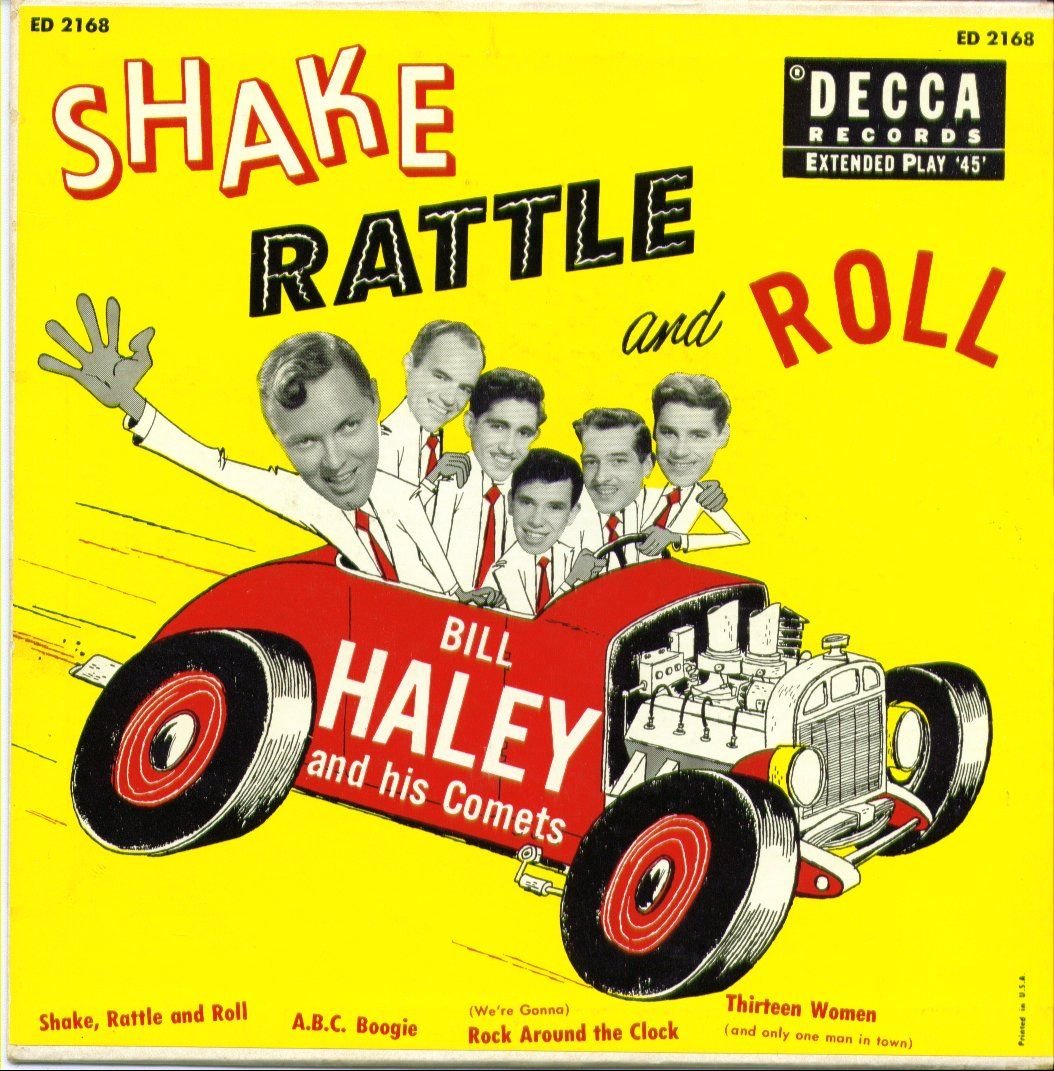

Shake, Rattle, and Roll

The Bible may be the world’s most surprising book. Just when you thought you had God down, you will read something that causes even the dead to rise up and say, “What was that?”

Parashat Vayera, Genesis 18:1–22:24

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann

If the Bible is not a book that surprises you, you are not reading it at all, not paying attention, or simply reading your own views into it.

The Bible may be the world’s most surprising book. Just when you thought you had God down, you will read something that causes even the dead to rise up and say, “What was that?”

This week’s parasha is one of those that just might shake, rattle, and roll the dead, and even some of us.

The first shaker is Avraham fudging on the identity of his wife so as not to tempt the people of the land to take her and knock him off (Gen 20:1–2). I remember discussing this with an Orthodox Jewish airliner seatmate who insisted we should congratulate the patriarch for his cleverness here. I disappointed the man by pointing out how the Torah puts words of moral rebuke into the mouth of pagan king Avimelech, shaming Avraham (Gen 20:9).

This is the second shake-rattle-and-roll in our text: the pagan king as moral arc-light. He is appalled when God tells him Sarah is Avraham’s wife, not his sister. This shaker reminds us of the Book of Jonah, where pagan sailors do everything right while the prophet of God is finding escape routes from doing the will of his Master.

The third resurrecting realization is that even though Abraham is a moral failure in this account, God still considers him a prophet. As a prophet, he has authority to pray, which, when offered, brings healing to Abimelech’s household (Gen 20:7).

What then should we make of these three shakes, rattles, and rolls?

First, we need to reconsider the sharp lines we often draw between God’s good soldiers and “the world.” These lines make for tidy thinking but have little to do with reality. Here in our story, we see the “believer,” the “good guy,” doing the bad things, and the “unbeliever”—the godless pagan—rightly perceiving the still small voice.

We all put some people groups on a pedestal while other we just put down. We make excuses for the ingroup, and make jokes about the others. Our party is the party of God and its platform written on tablets of stone with his finger. The other party has horns and a tail and smells of sulphur. For many people this is the obvious truth, but for a God who looks beyond outward appearances into the hearts of humans, it’s obviously an illusion.

This kind of categorical thinking about religion, politics, and people, is wrong. One way we know it’s wrong is that life is not like that—good people do bad things, bad people do good things, and sometimes it’s impossible to tell the bad guys from the good ones.

When it comes to biased judgments, religious people are well-known offenders, muscular in their judgments, and atrophied in their capacity to criticize themselves or their crowd.

Our parasha chastens and reminds us that sometimes you can’t tell the good guys from the bad guys without a score card, reminding us as well to make sure our score card is the same as the one in the hand of the Holy One.

Anne Lamott warned us: “You can safely assume that you've created God in your own image when it turns out that God hates all the same people you do.” And even though she’s a flaming liberal, she’s got it right, doesn’t she? Imagine that. If you can!

It’s past time to learn our lessons well.

First, we need to learn to not pile on or desert someone who fails to measure up to our image of them. They are not usually bad people. But all of us are a work in process. Let’s offer them a proper measure of support, not too much, not too little, and see what happens. If, instead, we throw stones or turn our backs on them, we sabotage their progress or miss the chance to celebrate their growth.

Yiftach was an illegitimate child whose brothers and the Gileadite elders drove out of town as just so much trash. Years later, when Gilead and all Israel were under attack by the Ammonites, these elders knew enough to send a delegation to recruit Yiftach to help them. He alone had the leadership skills to fight off the enemy (see Shoftim/Judges 11:1–11). Imagine what would have happened if they had simply persisted in writing him off!

Second, we need to learn to not idolize people, putting them on pedestals. Makers of idols are worshipers of lies. When we treat others as icons of perfection, we set ourselves up for disappointment, and them, for a fall. Again, we are all works in process, and our lives are most often two steps forward, one step back, or some variation on the theme. Let’s try to be part of other peoples’ solutions, and not their problems.

Third, we need to realize that everyone is in process. Even giants stumble. And Shorty Zacchaeus became the big guy in town (Luke 19:1–10). Holiness takes practice. Give people space. Yes, even relatives and close friends will disappoint you. But even strangers can astound you in all the best ways. Keep your eyes open, and your heart from being closed.

Avraham only expected unrighteousness from pagans, believing they would kill him to get at his beautiful wife. He was wrong. Some of us may expect nothing good from Democrats, Republicans, Liberals, Conservatives, immigrants, Palestinians, or Muslims. Let’s be careful we don’t make ourselves morally and spiritually blind and deaf.

Nothing I am saying justifies moral relativism. We must never forget this warning, “Oy to those who call evil good and good evil, who present darkness as light and light as darkness, who present bitter as sweet, and sweet as bitter!” (Isaiah 5:20). Evil should never be given the benefit of the doubt.

But neither can we justify being hard-nosed. We all need to seek and be prepared to find the grace, truth, and goodness in the discounted other. Our continual need is balance.

Pray for eyes to see the glimmer of God’s image whenever and however it appears. But don’t go through life with your eyes shut.

Wise as serpents. Harmless as doves.

Shake. Rattle. And roll.

It’s About the People

The events of the last several weeks in Israel have left all of us with a plethora of unchecked emotions. Many of us are experiencing extreme anger, and a cloud of darkness seems to hover forebodingly. In this age, war might be inevitable. Few of us can change the trajectory of violence. But we can decide how we relate to the specter of war.

Playground bomb shelter in Sderot, Israel

Parashat Lech Lecha, Genesis 12:1–17:27

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Congregation Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

In April 2003, on the eve of the Second Gulf War, I attended a forum of four Nobel Peace laureates. Though the United States invasion the next day proved to be misguided, the words of Elie Wiesel that evening stood out to me as an unfortunate truism. No doubt he shared from the perspective of his own experience of World War Two and the ensuing liberation of Holocaust survivors. He stated, “No war is just, but some wars are necessary.” I recall wondering who gets to make such a determination.

The events of the last several weeks in Israel have left all of us with a plethora of unchecked emotions. Many of us are experiencing extreme anger, and a cloud of darkness seems to hover forebodingly. In this age, war might be inevitable. Few of us can change the trajectory of violence. But we can decide how we relate to the specter of war.

This week’s parasha records the call of Abraham, the first Hebrew, and what is understood as the genesis of the Jewish experience. It includes two well-known affirmations—the promise of progeny to Abraham, and the blessing of Abraham by Malchi-Tzedek king of Salem (Gen 14:18–20). But wedged between is a much less-preached story of war that contains important lessons for us. Abram, as he was originally called, allies himself with the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah, as well as other tribal leaders, to liberate his nephew Lot, his family, and their possessions. I suppose there are several lessons we can gain from this terse narrative. But we can learn from at least two things Abraham does right, and one that he could have done better.

Lesson 1—Give God his due (Gen 14:23)

As a reward for not profiteering off the war, and relying upon his God, Abram is rewarded.

Abram said to the king of Sodom, “I raise my hand in oath to Adonai, El Elyon, Creator of heaven and earth. Not a thread or even a sandal strap of all that is yours will I take, so you will not say, ‘I've made Abram rich!’”

According to the sages of the Talmud, Abraham’s descendants are given the mitzvot of the blue thread of tzitzit and the straps of tefillin as a reward for this response (Sotah 17a). By declining the spoils of war, Abraham attributes the victory to God and not his own military prowess. The mitzvot are reminders that the Holy One is always near to his people. It is God who provides and protects.

Lesson 2—Give others their due (14:24)

I claim nothing but what the young men have eaten, and the share of the men who went with me—Aner, Eschol, and Mamre—let them take their share.

Abraham properly repaid those whom he enlisted, and he fed his men adequately. While he refused any bounty from war, he recognized that those who risked their lives defending and liberating his kin were entitled to remuneration and provision.

Lesson 3—Put people first (14:21)

Rabbi Yochanan asks (Nedarim 32a), “Why was Abraham our father punished that his descendants were enslaved in Egypt for 210 years? Because he prevented people from entering under the wings of the Shekinah, that is, from believing in God.” For it says that after the victory over the four kings Abraham returned all captured property, whereupon the king of Sodom said to Abraham, “Give me back the people. You can keep the goods.” Abraham should have insisted on taking the people with him to teach them to believe in God.

Though this is a fanciful accounting derived from Abraham’s silence, it makes a salient point. Perhaps if the people had not returned to Sodom their inevitable fate might have been different when the city was destroyed. It seems right that we answer the divine query by simply assuming we are our brother’s keeper. If we give the Holy One his due, provide for those who protect our freedom, and put people first, perhaps we can find some light amidst the present darkness.

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

The Original Influencer

The people around us influence us, and it is nearly impossible to avoid that. In this week’s parasha, however, we see two examples of people fighting and winning the fight against the negative influences around them. The first example is Noach.

Russell Crowe as Noah

Parashat Noach, Genesis 6:9–11:32

Daniel Vinokuroff, UMJC Young Adult Chair

In many different cultures, we have very similar things. These cultures might be on opposite sides of the world, yet their origin stories, their mythologies, their ideas of righteousness, and even certain phrases, can be eerily similar. We can talk about many examples, yet one comes to mind that relates to this parasha. There is a wise saying in Russian, and I have since learned that it exists in many other cultures, including Spanish, that says, “Tell me who your friends are and I will tell you who you are.” This says that the people around us influence us, and it is nearly impossible to avoid that. In this week’s parasha, however, we see two examples of people fighting and winning the fight against the negative influences around them.

The first example is Noach. He is called the only one who is righteous in his generation. He defies all odds and stays faithful to Hashem throughout his lifetime before the flood, and thereby is called righteous. We can see who talked into his life by looking at the genealogies and doing the calculations of years. Noach was taught the ways of Hashem by his forefathers (except Enoch who was taken by Hashem). He could have even met Enosh (Adam’s grandson) as a little boy. We see all of this in Genesis 5. We also read that the flood happened in Noach’s 600th year (7:6). Hashem first watched him and saw that he stayed faithful and righteous. It seems that the previous generations started to walk away from Hashem more and more. For whatever reason, Noach did not have children until he was 500 years old. He then had three sons and was able to raise and teach them for nearly 100 years before the flood waters came.

Yet we see that the influence of the father was not enough to guard the sons from the influence of the world. This is evident as Ham makes fun of or embarrasses his father a few years later. The scriptures seem to indicate that Canaan, the son of Ham, was also heavily involved in this deed, as this is the reason for him to be cursed (9:25). A different son of Ham, Kush, takes the people at the time and builds a huge empire with Babel as one of its cities (10:10). Idolatry is involved as the inhabitants seek to make a name for themselves through building a tower with its top in the heavens (11:4). They should know from firsthand accounts what Hashem has done for them and how he saved their forefathers, for after all Noach is the grandfather of Kush. Yet, we see that the influence of one godly generation was not enough for all other generations.

Our second example in this portion is Abraham, descended from Shem who was blessed by Noach, “May God . . . dwell in the tents of Shem” (9:27). How did Abraham get his godly example so that he could also be an example of godly influence? Without understanding the genealogies, we will not completely understand this. Hashem would not have told him to go to the land of Canaan if he were not a righteous man, for he hates wickedness and delights in righteousness (Psalm 45:7). Therefore Abraham was first observed by Hashem (our sages like Rabbeinu Bahya, Rashi, and Ramban point this out too), as Hashem does not pick people at random. Abraham’s faith in Hashem is what made him do righteous acts. How did he develop this faith?

In the genealogies of chapter 10, we learn that Kush, a descendant of Shem’s brother Ham, reigned over the Mesopotamian area of civilization as he built many of the cities, including the Chaldean cities. From this, we can also deduce that he is the one who built the tower of Babel. At first glance, one could say that all people live here. However, we see that some people leave this area in what appears to be before the building of the Tower, people like Asshur (10:11). Rashi comments, “As soon as Asshur saw that his sons listened to Nimrod, rebelling against the Omnipresent by building the Tower, he went forth out of their midst.” Who is this Asshur? According to Rabbeinu Bahya, Radak, and Ramban, he is one of Shem’s sons (10:22), who did not agree or want to have an ungodly influence. When we look at Genesis 10:21, we find that Shem is the father of the descendants of Eber. Ramban says, “This means that he was the father of all who dwelled beyond (eber) the Euphrates River, which was the place of Abraham’s family.” This is said from the perspective that the entire civilized world is east of the Euphrates at this time and to be beyond the river would mean you are west of the river. This is seen to be the case as they eventually traveled west to Haran (11:30).

The story of Abraham, however, begins with his father in Ur. They have been there long enough for his youngest brother to be born there (11:28). It seems that Terah took his family to the city of Ur later in life. This is seen in the light of a later passage when it talks about how Abraham is not from the Ur of the Chaldeans, but Hashem brought him out of it. Joshua 24:2 “In olden times, your ancestors—Terah, father of Abraham and father of Nahor—lived beyond the Euphrates and worshiped other gods.’” Terah worshiped other gods, so how is it that Abraham is adamant about the one true God? Where did he learn this from? Who is the influencer of Abraham? When we look at the ages of everyone involved, we see that Shem is still alive at the time of Abraham, probably away from the influences of Kush. Not only Shem, but Noach himself was alive until Abraham was about 60 years old. Shem lived for another 110 years after the birth of Abraham. Therefore one can surmise that the godly influence of Noach and Shem influenced Abraham to be righteous. Someone needed to tell and show Abraham about this mighty God and teach his way. In turn, Abraham became the father of a great nation that influences the world to this day.

So what does this mean for us? Well, what are we doing in this chaotic world around us? Are we influencing people for Hashem and being that light to the world that we are called to be? Or are we letting the world influence us? Who are we hanging out with? These past few weeks have not been easy for us, and many wish harm to us and Israel. Are we going to let them influence us in how we act? Or shall we stay strong in Hashem, knowing that he controls all? One way you can influence others is through standing with Israel.

We may not be able to influence everyone toward Hashem, but even if we can influence one person, that person may be the next Abraham. Hashem might even be able to use us in a mighty way, but only if we are righteous and can influence others toward Hashem.

My name is Daniel Vinokuroff, and I’m the Chair of the UMJC Young Adult Committee. We seek to influence and support our young adults as they walk with Hashem while living a Jewish lifestyle. Follow us on Instagram at #UMJCYoungAdults to see what we are doing, or contact me at daniel.vinokuroff@gmail.com.

How to Respond in an Evil Day

This week’s Torah portion, Genesis 1:1–6:8, is indispensable, as it sheds light on how to respond in an evil day. The guidance provided in Genesis is not glib or simplistic; it does not minimize the reality of evil in our world, or try to explain it away.

Photo: BNN.network

Parashat B’reisheet, Genesis 1:1–6:8

Russ Resnik, UMJC Rabbinic Counsel

We might be tempted, amid the unthinkable events of recent days, to set aside our weekly Torah discussion and focus entirely on the war in Israel. Earlier this week, my colleague Stephanie Hamman, director of UMJC’s Ashreinu School, wrote about a similar temptation, to suspend the school’s online children’s classes for a week in light of the horrific story that was unfolding in Israel. Instead, she was “deeply convicted that the very best response we can have is to set our minds to studying Hashem’s instruction and the beautiful culture He’s given us to reflect His heart and purposes to the world. As a people we will outlive every oppressor, but it will be because of His covenant love.”

I agree, of course. A savage attack on the holy day of Simchat Torah—Rejoicing in the Torah—demands a response that includes more Torah, not less. (Simchat Torah was celebrated on Saturday, the day of the attack, in Israel and Sunday in the diaspora.) A barbaric attack on the day we renew our cycle of Torah readings must not divert us from renewing that cycle. Indeed, this week’s reading, Genesis 1:1–6:8, is indispensable, as it sheds light on how to respond in an evil day.

The guidance provided in Genesis is not glib or simplistic; it does not minimize the reality of evil in our world, or try to explain it away.

Most people around us won’t accept simplistic answers. We live in a time of increasing unbelief, but for every doctrinaire atheist we might encounter, there’s a dozen genuinely questioning souls who can’t commit to either faith or the denial of faith. Many desire to know a God who is present, real, and loving, but stumble over the mystery of evil in the world. If God is all-good and all-powerful, the Creator of everything (as we learn in this week’s parasha), how can there be so much evil in the world? To cast that question in terms of the horrific events of recent days, how can an all-powerful, loving God let children and parents be murdered in their beds, or be carried off as hostages by heartless men? How can he allow the wanton destruction and cruelty that’s been all-too-real on our screens this week?

Such questions become even tougher as we read the creation account. When the Creator finishes his work, he looks upon all he has made and sees that it is “very good” (Gen 1:31). But how can such things as we’ve seen this week happen in a “very good” world, and how can we believe in a good, all-powerful Creator when such things happen? From such questions arise abundant doubts. Our parasha does not address all these doubts or provide one nice tidy answer, but it does provide a framework for understanding and responding to the realities we see in this world, even on an evil day.

Three main points stand out to me:

The “very good” creation is not finished or perfect, and humans have genuine responsibility for moving it toward perfection. After creating the first two humans, God tells them: “Be fruitful and multiply, fill the land, and conquer it. Rule over the fish of the sea, the flying creatures of the sky, and over every animal that crawls on the land” (Gen 1:28). A perfect creation would not need to be conquered or ruled over. Likewise, soon after God creates Adam, he places him in a garden, by definition a guarded place, amidst the still-unconquered creation. There, Adam is not to dwell in innocent passivity. Rather, the Lord assigns him real responsibility, “to cultivate and watch over it” (Gen 2:15). And it’s there in the garden, of course, that humankind falls short in that responsibility, and disorder gains an upper hand, as is still evident today.

Within this imperfect world we will encounter reminders of God’s compassion. The not-perfect world where we still live is made far worse by mankind’s rebellion. Even here, though, we can look for glimmers of God’s merciful presence and embrace them, and sometimes see them grow into something far brighter. After Adam and Eve sinned, God promised that a descendant of the woman would crush the head of the serpent that deceived her (Gen 3:15), a hope-fueling assurance of redemption to come. In the meantime, God had to drive Adam and his wife out of the Garden, but he made them “tunics of skin and . . . clothed them” (Gen 3:21). Soon after, he showed a similar mercy to Cain the murderer by putting a mark upon him “so that anyone who found him would not strike him down” in retaliation (Gen 4:15). Even amidst sin and judgment there are glimmers of hope and compassion, if we have eyes to see them. We are to be especially watchful in an evil day and not give in to despair.

As partners in the created order, we can create glimmers of hope ourselves. Our mother Eve provides an example. After promising her a serpent-crushing descendant, the Lord tells her, “I will greatly increase your pain from conception to labor. In pain will you give birth to children” (Gen 3:16). But, pain or not, Eve does give birth. She chooses life and continuity despite the pain. Even after the devastating loss of one son, Abel, murdered by his own brother, Eve conceives again and gives birth to another son, whom she names Seth, or Appointed. “For God has appointed me another seed in place of Abel” (Gen 4:25). Seth is the offspring of hope, and in turn becomes, like his mother, a bearer of hope. It’s in his time, after the birth of his son, Enosh—a name that, “like Adam, means ‘man’ but which puts the emphasis on the basic frailty of man” (Nahum Sarna, JPS Torah Commentary)—that “people began to call on Adonai’s Name” (Gen 4:26). This phrase records the origin of prayer, as Sarna goes on to note: “It is the consciousness of human frailty, symbolized by the name Enosh, that heightens man’s awareness of utter dependence upon God, a situation that intuitively evokes prayer.”

So, how do we respond on an evil day? At such a time, we may try to reassure ourselves and others by saying “our thoughts and prayers are with you.” Some people criticize this sort of saying as superficial, as a pious phrase that doesn’t accomplish anything. Nevertheless, in the face of the unthinkable, we do intuitively turn to prayer, and the picture of God in Genesis should encourage us to do just that. Even, or especially, when we don’t know what to do, prayer is the right response.

We also respond by continuing to live in hope and compassion, watching for openings to treat others with respect and generosity. Such opportunities often emerge in the dark times, but also within the ordinary contours of our lives, if we keep our eyes open.

The Creation narrative doesn’t purport to answer every possible question, including questions raised by the outbreak of evil into our world. It recognizes that we live in a world where human wickedness sometimes seems to have free rein, and also that we can find hope even within such a world. We can respond on an evil day by recognizing the mercy that God provides, by taking hold and acting upon it, including through prayer—and thereby becoming bearers of hope ourselves.

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV)

“Friends, Romans, Countrymen, Lend Me Your . . . Year!”

In “Julius Caesar,” William Shakespeare takes the liberty of putting these words in Mark Anthony’s mouth: “Friends, Romans, countrymen; lend me your ears.” In the drama called life, Judaism takes the liberty of representing the Creator pleading: “Friends and Hebrew countrymen lend me your year.”

Shemini Atzeret–Simchat Torah 5784

By Dr Jeffrey Seif

Executive Director, Union of Messianic Jewish Congregations

In “Julius Caesar,” William Shakespeare takes the liberty of creatively putting the following words in Mark Anthony’s mouth: “Friends, Romans, countrymen; lend me your ears.” In the drama called life, Judaism takes the liberty of representing the Creator pleading with his creation: “Friends and Hebrew countrymen lend me your year.” Okay, I made it up. . . . Doesn’t exactly say that. Judaism does, however, beckon constituents to give Torah an ear for a year.

In the Diaspora, Shemini Atzeret (the eighth day of Sukkot) is followed by Simchat Torah (joy of the Torah), during which time the faithful focus upon and celebrate the Torah. Interestingly, God’s people are actually required to rejoice in the process—difficulties notwithstanding. Commenting on the mandate ve-samachta be-chagekha (that is, “you shall rejoice in your festival”), the Gaon of Vilna opined it was “the most difficult command in the Torah”—for obvious reasons. Harking to the command’s adherence amidst the turbulence of extremely trying times, Elie Wiesel commented that, even during the Holocaust, when it was “impossible to observe” the requirement to “rejoice,” Jews nevertheless “observed it” and rejoiced (Paul Steinberg, Celebrating the Jewish Year: The Fall Holidays [Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2007], 149). How does one do that amidst the turbulence of such trying times?

The notion of making oneself rejoice is hard to fathom. Seems one must possess a strong internal locus of control and have some object to focus upon besides one’s circumstances. Bounced around and affected as we too often are by external circumstances, we do well to focus on something beyond our circumstances. Focusing energies on something external helps stave off deleterious internal emotions that can plunge us into disorientation and despair. In Judaism, we are exhorted to make God’s Word the object of focus and adoration.

In Israel, Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah are combined into one day, with Simchat Torah marking both the end of the annual cycle of Torah reading (in Deuteronomy) and the restarting of the reading cycle for the new year (in Genesis). This public Torah reading tradition actually began in the Talmudic era (around the sixth century CE), with a pattern called the “Palestinian triennial.” Unlike our current one-year reading cycle, the triennial took three years to complete. Babylonian Jews, however, didn’t abide the lengthy practice followed in the land of Israel. By contrast, they divided the portions into the 50+ segments we call parshiyot—referencing segments of Masoretic texts in the Tanakh. In 1988, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement ratified and expanded the 50+ weekly reading segments, with their now being standard fare in Jewish communal experience.

Steady and disciplined exposure to biblical literature over time has an ameliorating impact on human experience. Mindful of that, we would do well to challenge ourselves—and others—to take seriously the demand to give God a concentrated year of Torah study. Were we to do so at the start of 5784, and keep a journal in the process of our so doing, we would discover that, in ways, we would be a different and better person by the time we get to 5785. Try it. Without detracting from the point I am trying to make here, it is worth noting the original intention of the holiday was different—though human betterment was indeed the object.

The maftir (concluding reading) for Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah is Numbers 29:35–30:1. The text recounts the mandate for the eighth day celebration. Recollecting the Torah isn’t mentioned. There, Israel is beckoned to cease from day-to-day labors and assemble before the Lord at the Mishkan / Beit HaMikdash (v. 35), bring special, seasonal sacrifices (vv. 36-38), and properly prepare those sacrifices along with those that are not season-specific (v. 39). The biblical tradition is tethered to bringing a Temple sacrifice; the synagogal tradition—noted above—is tethered to making a sacrifice: both are understood to pay great dividends.

New Covenant believers rightly understand Yeshua—the Word made flesh—to be the ultimate sacrifice. What too many believers miss, however, is the need to personally be sacrificial after receiving the ultimate sacrifice. For this, assembling proximate to the Word on a weekly basis is adjudged to be meritorious, as is paying ongoing attention to biblical revelation. Doing so elicits new and improved life forms around and within us.

On the Feast’s last day, Hoshana Raba, judgment decisions are said to have run their course. It is said: “During the festival of Sukkot the world as as a whole is judged for water, and for the blessings of the fruit of the crops” (Eliyahu Kitov, The Book of Our Heritage [Jerusalem / New York: Feldheim, 1978], 204; cf. 211-214). Interestingly, Yeshua’s word during Sukkot in John 7 seems to corroborate the point (see vv. 2, 8, 10 and 14). In vv. 37–38, John notes: “On the last and greatest day of the Feast, Yeshua stood up and cried out loudly, ‘If anyone is thirsty let him [or her] come to me and drink. Whoever believes in me, as the Scripture says, out of his [or her] innermost being will flow rivers of living water’” (TLV). To paraphrase, Yeshua said: “Hey—you want water and refreshment? Come to me!” He is the source of the water.

I heard him and came to him years ago. I know I need to keep on coming. . . . As we walk through 5784, let’s make frequenting our congregations a priority. Let’s take bringing forth the Torah seriously and let’s practice the implications of the words noted in it and expounded from it. It is my prayer that you as an individual, and we as a collection of congregations, be sufficiently watered and grow in the coming year. Give him your ear this year. You’ll be so glad you did.

Sukkot and Your Divine Purpose

With the arrival of the month of Tishrei, we enter the serious yet strangely joyous High Holy Day season. What starts with teshuvah/repentance at Rosh Hashana will be sealed on the judgment day of Yom Kippur. As if to give us all a divine break, we have five days from the close of Yom Kippur to the next major holiday: Sukkot.

This week we feature a special message for Sukkot by UMJC President, Rabbi Barney Kasdan.

This is truly an amazing time of year! With the arrival of the month of Tishrei, the Jewish world commemorates the serious yet strangely joyous High Holy Day season. What starts with teshuvah/repentance at Rosh Hashana will be sealed on the judgment day of Yom Kippur. As if to give us all a divine break, we have five days from the close of Yom Kippur to the next major holiday: Sukkot. Although called “the time of our rejoicing,” the Feast of Tabernacles is not without its serious side. Yes, there is the joy of building and dwelling in the sukkah at home and at shul. There are the festival meals with family and friends. And, of course, waving the lulav/palm branch to remind us of the physical blessings from our Heavenly Father.

Intermingled with the joy of the eight-day holiday, however, is a rather sober lesson in life. The scroll read for the festival is Kohelet/Ecclesiastes, which is a serious reminder of some of the realities of life. Solomon, the son of David, shares some of his vast experience with us every Sukkot. Interestingly, the rabbis note that Solomon penned his three famous works at crucial stages of his own life. Song of Songs was penned as a young man in courtship. Proverbs contains wisdom from his mid-life perspective. The final scroll, Kohelet, contains his reflections at the end of his days (Midrash Shir HaShirim 1:1). If that is the case, it is striking that the scroll of Kohelet starts with the exclamation “chavel chavelim/vanity of vanities!” Upon reflecting over his illustrious life, Solomon summarizes that it is essentially empty! What profit is a person’s work? Generations come and go. The sun rises and the wind blows, but what really changes? (Eccl 1:1–7). Simply put, there are so many things beyond our control. This could be very depressing or it could lead us to an entirely different direction. Now it becomes clearer why Megillat Kohelet is read every Sukkot. In the midst of the joy of the harvest and material blessings, we are reminded of the frailty of life. Who can control the twists and turns of life? The sukkah reminds us that there is a much bigger picture than even our current situation.

Additionally, Kohelet acknowledges that any innovations of mankind are rather meager in their importance. All things toil in weariness; the eye and the ear are never quite satisfied (1:8). Ultimately, “there is nothing new under the sun” (1:9). Our society is constantly looking for the latest gadget or phone upgrade to improve our existence. The incredible advance of technology impresses many. Yet, when a hurricane or pandemic hits, the world is suddenly shocked back into reality. For all our advances we are still so far from Paradise. How appropriate that we meditate on the lessons of Kohelet while we dwell in our simple sukkah. Whatever the blessings and benefits of our technologically advanced society, we are called to reflect on the simple realities of life. This time of year we are to get back to the wilderness experience of our ancestors. Although they had none of the modern conveniences we enjoy, were they less advanced than us today? Maybe there are forgotten truths that our generation needs to rediscover at this season of Sukkot.

Solomon goes on for chapters about the vanity of much of life. Yet, at the very end of the scroll, he summarizes his secret to living a fulfilled and purposeful life. “The end of the matter, all having been heard: fear God and keep His commandments” (12:13).

Even though life is fragile and unpredictable, there is a divine purpose. Despite the fact that all the busy activity of mankind is so meager, we are all here for a reason. Perhaps one of the best secrets of life is revealed at this time of year during Sukkot. Ultimately, all is vanity unless God is in the picture.

How fitting it is that it was on this festival that our Messiah gave a vital public message on the Temple Mount. “Now on the last day, the great day of the feast, Yeshua stood and cried out, saying, ‘If any man is thirsty, let him come to me and drink. He who believes in me, as the Scriptures said, from his innermost being shall flow rivers of living water’” (Yochanan/John 7:37–38). Messiah came to give us that personal connection to Hashem and to a life of meaning.

The sukkah, while reminding us of the vanity of this life, also holds forth the meaning of real life. May we all have a renewed perspective on our lives as we dwell in the sukkah for the eight days. Chag Sameach!