commentarY

Finding Life in Egypt

Our parasha begins, Vayechi Yaakov, “Jacob lived in the land of Egypt seventeen years.” The language of this opening line is somewhat unexpected. Why say that Jacob lived in the land of Egypt? In English translation it’s unremarkable, but there are other verbs that might have worked in Hebrew.

Parashat Vayechi, Genesis 47:28–50:26

David Nichol, Ruach Israel, Needham, MA

Our parasha begins, Vayechi Yaakov be’eretz Mitzraim, “Jacob lived (vayechi) in the land of Egypt.” The language of this opening line is somewhat unexpected. Why say that Jacob lived in the land of Egypt? In English translation it’s perhaps unremarkable, but there are other verbs that might have worked in Hebrew. Perhaps “dwelt” (vayeshev), as Isaac did in Canaan (Gen 37:1), or sojourned (vayagor), as Abraham in Gerar (20:1). It might well be translated “and Jacob really lived in the land of Egypt.”

Rabbi Yehudah Leib Alter of Ger (known as the Sfat Emet, 1847-1905) notices this as well:

Scripture could have just said, “Jacob was in the land of Egypt.” It wanted to teach that he was truly alive, even in Egypt. “Life” here means being attached to the root and source from which the life-force ever flows.

The Sfat Emet is getting at an irony here. The reader expects Jacob to “sojourn” instead of “truly live” in Egypt because, as when Abraham moved to Gerar, moving to Egypt looks on its face like a detour, a distraction in the arc of Jacob’s life. He is supposed to build up a great nation in the land promised to him and to Isaac and Abraham before him. Relocating the entire mishpacha to Egypt—right when they are poised to take the next step in growing into a nation—seems like a step in the wrong direction.

Indeed, we have evidence that Jacob himself feels this way. When his sons report the happy conclusion of their trials and the news of Joseph, Jacob’s heart “goes numb,” and only the strong evidence that his beloved son lives strengthens him to make the leap (Gen 45:26–28). Even after he sets out, God must give him further encouragement:

God called to Israel in a vision by night: “Jacob! Jacob!” He answered, “Here.” “I am God, the God of your father’s [house]. Fear not to go down to Egypt, for I will make you there into a great nation. I Myself will go down with you to Egypt, and I Myself will also bring you back; and Joseph’s hand shall close your eyes.” (Gen 46:2-4 JPS)

If we can read into the words of God’s encouragement here, Jacob is afraid that he is “shorting” the promise to become a great nation—selling the savings bonds before they mature, if you will. And what would keep his family of 70 people from assimilating into the greatest empire of the time? On paper, he would be giving up on the promise. To that end, God reassures him that this is in fact part of the story.

Yet this still doesn’t explain why Jacob is, in a sense, doubly connected to the “source of all things” while in Egypt. To understand this use of vayechi—related to chai, live—we must look at several earlier uses of that word in this narrative.

When Joseph can no longer hold back from reuniting with his brothers, he asks an unexpected question: “Does my father still live (Ha’od avi chai)?” (45:3). This is so confusing that the JPS translates it “is my father still well”? It’s unexpected because he already knows that his father is alive . . . it’s precisely so he won’t die that Judah pleads to bring Benjamin home!

The next cluster of occurrences of this word is when Jacob learns the news from his sons:

And they told him, “Joseph is still alive (od Yosef chai); yes, he is ruler over the whole land of Egypt.” His heart went numb, for he did not believe them. But when they recounted all that Joseph had said to them, and when he saw the wagons that Joseph had sent to transport him, the spirit of their father Jacob revived (vatechi ruach Ya’akov; literally, “the heart of Jacob became alive”). “Enough!” said Israel. “My son Joseph is still alive (od Yosef beni chai)! I must go and see him before I die.” (Gen 45:26-28 JPS).

Using these words in this way, the Torah is telling us more than the banal fact about Jacob staying alive and not dying for a certain number of years. Rather, he was revived; there was a quality about his life in Egypt that even surpassed the life he had in Canaan without Joseph.

I don’t think the text is saying that during his twilight years in Egypt Jacob “lived life to the fullest,” as in, he went to lots of parties, or that he took up woodworking, or started learning the saxophone. My guess is that with this choice of words, it tells us that Jacob was able to rekindle his faith that his life had meaning beyond what he could comprehend; God’s promises were not going to fizzle out when bad things happened.

This struggle is not foreign to us today. We may not literally be in Egypt, but we live in a world where redemption is incomplete, its processes hidden from us. Where are the nations beating weapons of war into implements of agriculture? How will our judges and counselors be restored as in days of old? Having left Egypt literally, we remain there figuratively: in exile—not just us but all the nations of the earth.

The metaphorical resurrection of Joseph restored Jacob’s ability to see God’s hand in both what he could see and what he couldn’t. In the same way, the resurrection of Yeshua enlivened the eyes of a handful of Jews in first century Judea. Having escaped Egypt only to live under the thumb of the Greek, then Roman empires, our ancestors perhaps could no longer perceive the arc of their story. They certainly would have been discouraged to learn that Jewish sovereignty would be another two millennia in coming.

Just as Jacob must reconcile the story he imagined with the way God was actually intending it to play out, so the first followers of Yeshua needed to adjust their expectations of what national redemption looked like.

Jacob’s heart is revived by his sons’ report that Joseph still lives, and rules over Egypt, but not right away. His heart first fails him and goes numb. According to the Ramban (Nachmanides, 1194-1270 CE) he is speechless and remains still for hours, and his sons have to yell Joseph’s words into his ears for the entire day, until the wagons arrive. And then, after hearing the words over and over again, and upon seeing all the bounteous goods from Joseph, his heart revives.

For those of us whose hearts are still numb, may we see Yeshua’s goodness to us in such quantity that it arrives by the wagonfull. And for those of us who have already seen it, may we truly live, connected to the source of all things, even as we live in Egypt, where the story’s arc is hidden from us. And may God, who brought us here, bring us back soon.

The Courage to Rise

Hundreds marched behind Martin Luther King and beside him, Abraham Joshua Heschel, who famously wrote later, “Legs are not lips and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words, our march was worship. I felt like our legs were praying.”

Parashat Vayigash: Genesis 44:18–47:27

Ben Volman, UMJC Canadian Regional Director

It is a moment when all seems lost. The sons of Israel were convinced that they had finally been reconciled with the intimidating vizier of Egypt. But their caravan had barely left the city gates, burdened down with crucial provisions, when they were overtaken by the vizier’s steward. He accused them of something impossible, stealing his master’s silver goblet. Despite their protests of innocence, after a careful search, the goblet was pulled out of Benjamin’s sack. In utter despair, they had turned back to face the most powerful man under Pharaoh. Now, this inscrutable Egyptian, who somehow had suspected the bloodguilt that stained their consciences, would have nothing to restrain his rage. There is even a painful note of confession from Judah as they are all prostrate before him: “God has revealed your servants’ guilt” (Gen 44:16).

And then—vayigash —Judah “approached” (CJB) or as others translate it, “went up” (NIV) to speak. Rabbinical tradition insists that we thoroughly study all that transpires from this heart-rending, humble intercession. He does not plead for himself, not even for the youth, but for the elderly father whose life is bound up with the fate of his youngest brother. Judah does not deny the vizier’s full right to exercise justice, but only begs to take his brother’s place.

The rabbis (Gen Rabbah 93:6) want us to consider all the scriptural nuances of the word vayigash that can be seen here: it is used before a charge into battle (2 Sam 10:13), a bold act of conciliation (Josh 14:6), and a prophet’s earnest call to prayer (1 Kings 18:36). We read the same word describing Avraham’s audacity as he bravely intercedes for the righteous who may yet be in Sodom (Gen 18:23). Judah’s courage in stepping forward is fully resonant with each of these situations.

All through the previous sidra, Mikketz, Joseph tested his brothers and each challenge, right up to this last one, revealed the hidden guilt for which they have no excuse. After all, what was the young Joseph’s offense when they sold him into slavery—being a dreamer? But each test had been equally difficult for Joseph who could not show them his tears. Now, Judah’s intercession is also a test for Joseph, who hears his brother’s mature note of compassion, regret, and even brokenness of spirit. “I couldn’t bear to see my father so overwhelmed with anguish” (Gen 44:34). How many of us, like Joseph, can look back with regret at our youthful arrogance and recall how we once imagined that the world should revolve around our dreams and shallow conceit? Until this moment, the man who had been sold into slavery and unjustly imprisoned for years had been holding them to account, but the one who has the right to judge may also choose to forgive.

To Judah’s brothers, anxiously waiting for a verdict, the sudden cry from the vizier for his attendants to leave the room is terrifying. For Joseph, weeping as he finally breaks all pretense of being a stranger, the time has come for healing. At first, when his brothers heard him speak, saying “Ani Yoseph”—“I am Joseph”—they recoiled in fear even before they could fully comprehend what was happening. But then, like a beloved brother, Joseph bids them to draw closer. There is no blame or reproach for the past. Everything has happened according to God’s purpose: “it was God who sent me ahead of you to preserve life” (Gen 45:5).

This is a man who is truly reconciled to the will of God. His message is an empowering word of life, first for his brothers, but also his father. When they arrive home and share the news, Israel can hardly believe it. We read that only “when he saw the wagons which Yosef had sent... the spirit of Ya’akov their father began to revive. Israel said, ‘Enough! My son Yosef is still alive! I must go and see him before I die” (Gen 45:27, 28). In a final plot twist to the story of Jacob who had spent decades in exile from the land of promise, he goes down to Egypt with God’s blessing. The God of his father tells him, “It is there that I will make you into a great nation. Not only will I go down with you to Egypt; but I will also bring you back here again, after Yosef has closed your eyes” (Gen 46:3–4).

A year ago, I was also writing on Vayigash for this commentary series, and I felt compelled to speak about faith that inspires hope in the shadow of difficult times. This year, it feels even harder to understand what is happening in the midst of our trials. But as I look at this story, I can’t help being inspired by Judah’s courage, stepping forward for the sake of his brothers. As we look around at a world enflamed with antisemitism, we require that courage, trusting that God will not fail to uphold his promises to Israel. And we need to be strengthened in the Spirit by Yeshua, who first engaged us, and rose to bring life when it seemed that all was lost.

At times like this, it’s tempting to retreat and withdraw. It takes courage of heart to keep praying, to stay engaged with God, and to remember that the gates of prayer never close. Even in the darkest times, there are miracles to remind us how God is still reshaping history. In 1933, just a few months after the Nazis came to power in Germany, the young Abraham Joshua Heschel had submitted his brilliant dissertation on the prophets at the University of Berlin and passed the oral exams, but couldn’t receive a doctorate until the work was published. Unable to pay the cost, he needed to find a publisher. The book, Die Prophetie, was finally sponsored in 1935 by the Polish Academy of Sciences and somehow received official permission for a book by a Jewish author to be received into Nazi German bookstores. Without the degree Heschel would never have escaped Europe, and despite endless complications, he left Warsaw for England just weeks before the Germans invaded Poland. Heschel re-wrote his dissertation in English and it was published in 1962 as The Prophets. It remains an influential volume, but not only among Bible scholars.

Some months ago, in a documentary featuring the late, revered Congressman John Lewis, who had survived the dogs and billysticks of the Alabama State Police in Selma on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, he spoke about the inspiration that he and his friends found in Heschel’s book, underlining passages on every page. He was one of the hundreds who marched behind Martin Luther King and beside him, Abraham Joshua Heschel, across the bridge from Selma on their way to the Alabama state capital. Heschel famously wrote later, “Legs are not lips and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words, our march was worship. I felt like our legs were praying.” Vayigash, indeed. May we, also, be so fully engaged with God’s purposes for us during these challenging times.

All Scripture citations, unless otherwise noted, are from the Complete Jewish Bible.

A Life in Technicolor

Joseph was a dreamer and interpreter of amazing dreams, full of meaning. He was in an Egyptian prison after a convoluted sequence of events triggered by a gift–the Technicolor Dream Coat (Gen 37:3)—the resulting jealousy of his brothers, and his own dreams of his brothers bowing to him.

Photo: https://broadway.com

Parashat Miketz, Genesis 41:1-44:17

Suzy Linett, Devar Shalom, Ontario, California

Several years ago, I had the opportunity to see a live production of the classic musical Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat, with roots and themes from the story of Joseph, eleventh son of Jacob. The musical numbers were well done and quite lively. The flashy colors, dance moves, and dramatics put a different flair on the narrative than one might receive by reading the text alone.

Joseph was a dreamer and interpreter of amazing dreams, full of meaning. He was in an Egyptian prison after a convoluted sequence of events triggered by a gift–the Technicolor Dream Coat (Gen 37:3)—the resulting jealousy of his brothers, and his own dreams of his brothers bowing to him. Miketz, meaning “at the end of,” picks up at the end of two years during which Joseph was forgotten in prison. Now Pharaoh had disturbing dreams. Finally, Joseph’s ability to interpret dreams was remembered, and Joseph was brought to appear before Pharaoh. According to Genesis 37:2, Joseph was about 17 when he was sold into slavery, and was about 30 when he was called up to Pharaoh. After being summoned, “He shaved, changed his clothes, and came to Pharaoh” (Gen 41:14b).

Release from prison and entry into Pharaoh’s court must have been like switching from old black-and-white broadcasting to vibrant Technicolor indeed!

This time, instead of simply providing an interpretation, as he had done for two fellow prisoners, “Joseph answered Pharaoh saying, ‘It’s not within me. God will answer with shalom for Pharaoh’” (Gen 41:16). After Joseph interpreted the dreams correctly, he was appointed to oversee the project of building storehouses and saving for the lean years to come. Within a moment, Joseph was released from prison, given an Egyptian name which meant “decipherer of secrets,” and given an Egyptian priest’s daughter as a wife. Joseph built the storehouses, and ran a food distribution program during the famine. Cue the music – Joseph was in charge of the land and his world was turned into technicolor. Joseph had matured. No longer the prideful young son showing off his gifts, he had developed a servant’s heart for the people. As his dream foretold, the Egyptians, who worshiped the sun, moon, and stars, bowed down to him.

Meanwhile, believing Joseph was dead, Jacob sent ten of his remaining eleven sons to Egypt to buy food. He kept Benjamin, Joseph’s full brother, at home. The brothers came to Joseph and “bowed down before him,” in fulfillment of Joseph’s other dream years earlier, which had set off the chain of events leading to his current position. Joseph recognized them, but they did not know he was their long-lost brother. Joseph accused them of spying, imprisoned them for three days, and then released nine of the brothers, keeping Simeon as a hostage, and instructing them to return with Benjamin. The brothers realized that this disaster was due to their treatment of Joseph all those years ago, and repented. They did not know Joseph understood them. He heard their cries of teshuvah. Joseph had his stewards return the brothers’ money by placing it in the sacks of grain. The narrative continues and eventually Joseph is reunited with his brother Benjamin, but again does not reveal himself. The parasha ends with Joseph demanding that the brothers leave Benjamin behind, and letting the others go home.

As we review this story, several things come to mind.

Joseph never sent word to his father that he was alive during the years he was in bondage. As I wondered about that, I realized if Jacob had known, the events leading to Joseph saving his family from famine would not have occurred. Joseph knew the truth of his own dreams, and understood the events must come to pass. He had two dreams about his future that are recorded in Genesis. The first was that his brothers would bow to him, and the second that the sun, moon, and stars would do the same. Egyptians worshiped the sun, moon, and stars. As Joseph saved that nation, its inhabitants bowed to him.

It is interesting to me that this parasha always comes during this time of year. The days are shortened, darkness is increased. Yet we have the light of Hanukkah, and the days will get longer again. Joseph was in dark places, the pit and the jail, yet the light of the dreams and word of God promoted him into full technicolor.

I am struck by the revelation of the Technicolor prophecies both fulfilled and promised.

In 1 Corinthians 13:12, Paul wrote, “For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part, but then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known.” A life in Messiah is a life in Technicolor, and we will see clearly in the world to come. We are to wrap ourselves in the “garment of praise” (Isa 61:3). In Ephesians 6, Paul exhorts us to put on the “armor of God.” Our spiritual lives can be vibrant Technicolor despite the dreary black-and-white around us. We, like Joseph, can put on our own “Amazing Technicolor Dream Coats!”

With the love of our Heavenly Father, we can forgive. When the brothers repented—made teshuvah—they were saved from death and reunited. They, like Joseph, moved from black and white lives into full Technicolor of what the Lord had for them. The Lord offers us a Technicolor life in him also. When we repent and make teshuvah, we are saved from eternal death and darkness to be reunited as the Body of Messiah. Olam ha-zeh—this present world—can be gray and dreary. When we put on the coat, we enter into the Technicolor world here on earth and in Olam ha-ba, the world to come. “I will rejoice greatly in Adonai. My soul will be joyful in my God. For he has clothed me with garments of salvation” (Isa 61:10a). Live a Technicolor life!

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version, TLV.

Servants of the Holy, Servants of the Light

As we commemorate Hanukkah this year, let’s focus on the shamash candle, the servant light that brings light to the rest of the menorah and sheds that light to the entire house. Let’s focus on Yeshua the quintessential servant, who through his sacrificial life brings light to the entire world.

Parashat Vayeshev, Genesis 37:1–40:23, and Hanukkah 5784

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Congregation Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

Sometimes it would seem that the focus within American Judaism is on impressive edifices, building funds, synagogue attendance, and business protocols – and why not? These values merely mirror those of our everyday lives. Sadly, Judaism appears to have forgotten the purpose of Jewish identity. We were not called to be Jews in order to spread borscht belt humor or, believe it or not, to give the world the perfect bagel. Neither were we called to obsessively observe minutia for its own sake, pridefully demonstrating our superior piety. We were called, and are still enjoined, to be a “Kingdom of priests, a holy nation.” Our mission in the world is to embody a communal life that will concretize God’s highest values: holiness, learning, sensitivity, and justice. We are called to be a living testimony of the faithfulness of the Creator, who maintains his creation in love. We are summoned to be “Avda de-Kud’sha: Servants of the Holy One.”

But how can we as Jews serve God if our leaders and teachers are so uncomfortable speaking of God? Several years ago, I was a member of a clergy association in the town where Shuvah Yisrael met. Each month we met at a different church or synagogue. One month we met at one of the member synagogues. We were all given a tour of the rather impressive facility. The rabbi then told us of an upcoming trip that they would be making to “Jewish New York.” The synagogue had contracted three large coaches to make the trip. When asked if they would be able to fill the buses, the rabbi replied, “My people will go anywhere I tell them to, except the sanctuary.” He then bemoaned the fact that most members rarely attended worship on a regular basis. I was not surprised, though; this rabbi had always seemed uncomfortable with routine mention of God and public prayer. In fact, he seemed far more comfortable speaking about the latest politico than he did about the spiritual issues at the core of our communal existence.

So, if the world we occupy is not suitable for God, why do we earth dwellers need him? Since the rabbi had relegated God to the sanctuary on Saturday, why then would he expect his congregants to risk the same incarceration?

The patriarch Joseph provides a much better role model of the committed Jew. After he is sold into slavery to the house of Potiphar the Egyptian, we are told, “the Lord was with Joseph” (Gen 39:21). This statement is somewhat perplexing in that it seems so obvious. As the protagonist of his own biblical story, one would only assume this to be true. So, what else might the narrator be trying to tell us?

According to Rabbi Huna in Midrash B’reisheet Rabbah, Joseph “whispered God’s name whenever he came in and whenever he went out.” The idea is not only that God took an interest in Joseph, but more so that Joseph continuously cultivated a consciousness of God’s presence. By regularly invoking God’s love, Joseph trained himself to perceive the miraculous among the ordinary, to experience wonder in the midst of the mundane. By whispering God’s name, he allowed his own deeds to speak more loudly than words testifying of God’s ever-present love.

Rashi interprets “the Lord was with Joseph” differently. According to the great medieval commentator, “the name of God was often in his mouth.” So, Rashi believed that Joseph spoke about God, not only to God. Joseph’s willingness to speak openly of his relationship with God, his love for God, and his eagerness to serve God encouraged others to consider their own relationship with God. By speaking openly of God’s love for humanity and his own reciprocal devotion, Joseph challenged the conventions of those around him, provoking them to rethink their own assumptions about morality and the order of the universe.

Both interpretations, one of quiet piety, the other of a willingness to speak of God openly and frequently, have a place in Judaism and in our faith life. Sometimes we best testify to God’s loving care by simply embodying that love in the acts of caring for the homeless and visiting the sick and elderly. In such instances our hands are the hands of God and can speak much more eloquently than our mouths.

But there is also a time to speak about God and to speak up for God. Of course, we speak about God at our Torah studies and services. But do we take the time to thank God before and after meals, upon rising, and before going to bed? Would our children be surprised to find us praying with regularity? Do most of our articulated dreams and values begin and end with God’s clearest values?

Also, are there times when it is not enough to merely care for the homeless and the needy, but to speak out for them as well, to fight for those who cannot fight for themselves? Joseph was willing to speak up for fellow prisoners, though he was falsely accused himself. Like Joseph, can we take a stand for those who have been forgotten by society and even vilified by those in power? Yeshua, who embodied the purest presence of the Holy One, lived his life and sacrificed his life for all, especially the meekest, the humblest, and the neediest among us. He was truly a Messiah cast into the model of Joseph, the suffering servant. He also encouraged us to live lives dedicated to Hashem, taking up our crosses daily!

Can it be said of us, “the Lord was with (state your name)?” Our Messianic Judaism can be one that concretizes and enlivens our ancestral love for our Creator, Provider, and Protector, and honors the presence of Yeshua our Redeemer.

As we commemorate Hanukkah this year, let’s allow it to be more than a materialistic celebration of society’s verities. Let’s resist the temptation to overemphasize Jewish military might! Rather might we focus on the shamash candle, the servant light that brings light to the rest of the menorah and sheds that light to the entire house. Let’s focus on Yeshua the quintessential servant, who through his sacrificial life brings light to the entire world.

Then perhaps we can pronounce with conviction, “Ana avda de-Kud’sha b’rikh hu: We are the servants of the Holy Blessing One.”

You Know, You Are Also Right

Probably about once a month, I will think about this famous scene in “Fiddler on the Roof.” Tevye is observing a conversation between two men, arguing about whether we need to read the newspaper and be aware of outside events or not. He agrees with each one in turn by saying “You’re right.”

Parashat Vayishlach, Genesis 32:4-36:43

Rabbi David Wein, Tikvat Israel, Richmond, VA

Probably about once a month, I will think about this famous scene in “Fiddler on the Roof.” Tevye is observing a conversation between two men, arguing about whether we need to read the newspaper and be aware of outside events or not. He agrees with each one in turn by saying “You’re right.” Then, another man says, “Wait a minute, he is right and he is right? How can they both be right?” To which Tevye responds, “You know, you are also right.”

What I love about this is that it’s brilliant diplomacy and wisdom all at once. Some tensions in our theology and our lives are never fully resolved. These tensions are apparently opposing truths which are both correct. If you are married, you may have experienced this phenomenon. Now, I’m sure you are convinced in your mind that your way of doing the dishes is the correct way, but there may be something to the other person’s perspective that’s worth hearing out. The key to resolving this kind of impasse is to draw out the other person’s narrative, so that they feel seen, understood, and valued. The goal is not necessarily to be right. However, the only way that you could both be right is if you both are understood and valued. Easier said than done, but it is possible.

Pastor Peter Steinke (a disciple of Rabbi Edwin Friedman) describes the tension within a need we have in all our relationships: to be connected and to be an individual. In other words, we long to have loving affirmation and encouragement with one another and at the same time to be able to define ourselves rooted in the affirmation and encouragement of God. We seek neither to placate the other person for fear of rejection, nor to isolate from the other person for fear of conflict. We make decisions both out of compassion on the one hand, and out of a sense of values based on Scripture on the other. If we can learn to balance these two over time, we can mitigate conflict and partner with God for the repairing of the earth (Tikkun Olam). “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God” (Yeshua the Messiah in Matthew 5:9). I’m waiting for the day that I will meet my Maker and he will say, “You know, David, as a peacemaker, you were also right.” Dream big, eh?

And this brings us to this week’s parasha, featuring our dubious hero (or maybe anti-hero), Jacob. Having finagled both the birthright of the firstborn son and the blessing meant for Esau, Jacob is now scrambling and lowering himself to prepare to see his brother after twenty years. He sends gifts, he refers to Esau as “my lord” and himself as “your servant,” and he divides his camp so that if Esau destroys half of his family out of revenge, at least he has something left.

We know Jacob. We know he uses deception and manipulation, but we know he values the blessings of God. We know he is a heel grabber, but that doesn’t just make him an annoying noodge--he is also tenacious and resilient. Jacob acknowledges in this parasha that he is blessed beyond what he deserves, and aren’t we all? Are we really any better than our conflicted ancestor, the namesake of Israel? Listen to his prayer in preparation to meet his brother:

“O God of my father Abraham, and God of my father Isaac, Adonai, who said to me, ‘Return to your land and to your relatives and I will do good with you.’ I am unworthy of all the proofs of mercy and of all the dependability that You have shown to your servant. For with only my staff I crossed over this Jordan, and now I’ve become two camps. Deliver me, please, from my brother’s hand, from Esau’s hand, for I’m afraid of him that he’ll come and strike me—the mothers with the children. You Yourself said, ‘I will most certainly do good with you, and will make your seed like the sand of the sea that cannot be counted because of its abundance.’” (Gen 32:10-13, TLV)

It’s God’s faithfulness vs. Jacob’s character flaws. Who wins that wrestling match? So we ask, “Is Jacob actually repentant?” Perhaps only partially, but he is both humbled and bold. “Lord, you said you would do good to me and to my descendants, and even though I’m afraid of my brother, I trust you.”

Jacob’s story isn’t really just about Jacob. It’s about God. Many rabbis have tried to massage this story to make Jacob more acceptable and Esau more unacceptable. But we don’t need to apologize for Jacob. We are also acceptable only because of God’s sovereign love, and not because we are always shining examples “worthy” of that love. But God does accept Jacob, and he does accept us. God is known in the Scriptures as the God of Israel, and even sometimes as the God of Jacob. The Lord stakes his name, his reputation, his shem, on Jacob and his imperfect descendants, because God cannot be unfaithful to himself.

The Lord of armies is with us;

The God of Jacob is our stronghold. Selah. (Psalm 46:7 NASB)

Jacob wrestles with God, with his brother, and ultimately with himself. He “wins” the fight, but comes out limping. Formerly the blessing-grabber, he is now the longsuffering, blessing-holder--from Ya’akov to Yisrael. And us? We wrestle with Jacob in all his glorious flaws--we scratch our heads at him and say like that great Jewish sage, Jerry Seinfeld: “Really?!” But Jacob is us. The text is a mirror, and we are full of contradictions, truths apparently opposed to one another inside us like a kaleidoscope. But we’re still here. We’re still loved by God, and we’re holding on to the blessings, and more so clinging to the Blessing-Giver.

Keep going, keep loving, keep wrestling it out. The truth is, we’re all in process, and the process is messy and takes time. Give yourself grace. Progress, not perfection, as a friend reminded me recently. After all, God loved and was faithful to a rough-around-the-edges guy like Jacob to bring to bear his covenant promise, and to do good to him and his descendants, the Jewish people.

The conflicts between Jacob and Esau (Israel and Edom), Jacob and God, and Jacob and himself are a sample of all conflicts we experience. Messiah Yeshua reconciles us back to God, back to each other, and back together within ourselves.

For it pleased God to have his full being live in his Son and through his Son to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace through him, through having his Son shed his blood by being executed on a stake (Col. 1:19-20, CJB).

The gospel brings peace amongst the opposing forces within us and among us. So, the way to be right isn’t always to be correct. We are also right because we are made right, made cleansed, having received a right-ness as a gift through Messiah Yeshua. In that sense, you know, you are also right!

The Twelve Tribes and Beyond

Our tribal history contains the classic elements of being chosen, having a special legacy, and being different from (and perhaps superior to) the Other. But in typical fashion for the Torah, the account of tribal origins points beyond the usual motifs to hint at hope and transformation to come.

Parashat Vayetse, Genesis 28:10–32:3

Rabbi Russ Resnik

In the Jewish community, we sometimes identify ourselves as MOTs, Members of the Tribe. It’s a bit whimsical, but it’s also a bit problematic in our current social-political climate, where “tribalism” is not a happy term. Our Torah reading last week introduced Jacob, the father of the Twelve Tribes of which all Jews are members. The tribal history continues in this week’s parasha and contains the classic elements of being chosen, having a special legacy, and being different from (and perhaps superior to) the Other. But in typical fashion, the Torah’s account of tribal origins points beyond the usual motifs to hint at hope and transformation to come.

We saw last week how our forefather Jacob was caught up from before birth in a struggle with his brother Esau, a struggle that sounds pretty tribal from the outset. Their parents, Isaac and Rebekah, struggle with barrenness through the first twenty years of their marriage. Finally, Isaac prays for Rebekah and she becomes pregnant . . . with twins!

But the children struggled with one another inside her, and she said, “If it’s like this, why is this happening to me?” So she went to inquire of Adonai. Adonai said to her:

“Two nations are in your womb,

and two peoples from your body

will be separated.

One people will be stronger

than the other people,

but the older will serve the younger.” (Gen 25:22–23)

The younger is Jacob, of course, and his early years are marked by strife and competition with Esau, from whom Jacob gains both his birthright and his blessing (belonging to Esau as the first born, since he emerged from the womb just ahead of Jacob). The struggle with Esau becomes so intense that Jacob has to flee the land of promise in fear of his life, and this week’s parasha opens as Jacob begins his journey into exile. He spends the night in “a certain place,” where he dreams of a ladder or ramp joining heaven and earth, with the Lord appearing and saying to him,

I am Adonai, the God of your father Abraham and the God of Isaac. The land on which you lie, I will give it to you and to your seed. Your seed will be as the dust of the land, and you will burst forth to the west and to the east and to the north and to the south. And in you all the families of the earth will be blessed—and in your seed. (Gen 28:13–14)

Jacob is the founder of a tribe, but it’s a tribal story that points beyond itself, because Jacob’s seed, in line with the prophetic words given earlier to grandfather Abraham (Gen 12:3), will be the source of blessing for all the families of the earth. This Torah narrative is tribal, but universal as well, pointing to a future of blessing for all the earth’s inhabitants.

But there’s a more immediate and less noticeable thread in the tapestry of Jacob’s tribal story that also hints at a reality beyond tribalism—the humanity of Esau, the son not chosen. When Esau discovers in last week’s parasha that Jacob has received his father’s blessing instead of him, he begs Isaac, “‘Haven’t you saved a blessing for me? . . . Do you just have one blessing, my father? Bless me too, my father!’ And Esau lifted up his voice and wept” (Gen 27:36, 38). Esau is impulsive and unstable. He loses his birthright because he despises it (Gen 25:34). After Jacob diverts his blessing to himself, Esau vows to kill him, thus triggering Jacob’s twenty-year exile, which begins in this week’s parasha (Gen 27:41–45). But for all that, the Torah portrays his sorrow over losing the blessing with compassion. Esau is not the tribal Other, but a fully-formed human character, flawed but evoking our generosity.

Throughout Jacob’s trying twenty-year exile from the land of promise, Esau isn’t mentioned at all. Again, our founding narrative refrains from the sort of belligerence and chest-thumping we might expect in a tribal tale. Esau reappears only as the exile is about to end, coming to meet Jacob with what looks like a war party of 400 men. But when the two finally meet, the Torah again portrays Esau with generosity and deep emotional connection.

When Esau saw Jacob coming toward him, he “ran to meet him, hugged him, fell on his neck and kissed him—and they wept” (Gen 33:4). Then he tried to refuse Jacob’s gifts of tribute, saying, “I have plenty! O my brother, do keep all that belongs to you” (Gen 33:9), and offered to escort Jacob and his whole household back into the land of promise.

Jacob declines to go with Esau, which some of our sages commend as a wise move, because of Esau’s emotional instability. It may seem better to part company while the feelings are good and Jacob is safe. But finally the two do reunite, at the death of Isaac, to mourn their father together. “Then Isaac breathed his last and died, and was gathered to his peoples, old and full of days. So his sons Esau and Jacob buried him” (Gen 35:29). Tellingly, in this final scene, Esau is named first, before Jacob. This reunion, however brief, reminds us of the equally significant reunion of Isaac and Ishmael at the death of Abraham (Gen 25:8–9).

The Torah insists on weaving the bright thread of our shared humanity into the complex tapestry of Jacob’s tribal origins.

Last week, I had the privilege of joining over 200,000 Members of the Tribe and supporters in the March for Israel, calling for release of the Hamas hostages and opposing the current surge in antisemitism. As I was swept along with the crowd toward the U.S. Capitol, I thought of the psalmists’ words about joining the multitudes, the tribes going up to worship Hashem (Psa 42:5; 122:4). We were there to protest and advocate, not worship in the usual sense, but the feeling of tribal assembly was overwhelming. One of the speakers, historian Deborah Lipstadt, provided a healthy balance, amazingly linked to the current Torah readings: “Do not sink to the level of those who harass you, but do not cower. Jews are strongest at their broken places.”

Jews are strongest at their broken places, like our father Jacob, who returned from exile lame and leaning on his staff to be reunited with his brother-adversary Esau. Jacob is a model for his descendants. Our journey, like his, is one of vulnerability and struggle, but also one in which we are to recognize the humanity of the Other and thereby keep hope alive.

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

Keep Digging Those Wells

The Jewish spirit is a productive spirit. It works for the future and believes against all hope that the desert can indeed bloom. The Jewish spirit believes that through the diligent application of hard work in the land where we sojourn, we will not just survive, but we will thrive.

Parashat Tol’dot, Genesis 25:19-28:9

Matthew Absolon, Congregation Beth T'filah, Hollywood, FL

The reading for this week’s drash is a little longer than normal, as I want to capture the narrative laid out during this time of Isaac’s life. The Torah contrasts the values of Abraham and Isaac and, by extension, the values of God's chosen people, with the values of the heathen nations wherein they resided.

And Isaac sowed in that land and reaped in the same year a hundredfold. The Lord blessed him, and the man became rich, and gained more and more until he became very wealthy. He had possessions of flocks and herds and many servants, so that the Philistines envied him. (Now the Philistines had stopped and filled with earth all the wells that his father’s servants had dug in the days of Abraham his father.)

And Isaac dug again the wells of water that had been dug in the days of Abraham his father, which the Philistines had stopped after the death of Abraham. And he gave them the names that his father had given them. But when Isaac’s servants dug in the valley and found there a well of spring water, the herdsmen of Gerar quarreled with Isaac’s herdsmen, saying, “The water is ours.” So he called the name of the well Esek, because they contended with him. Then they dug another well, and they quarreled over that also, so he called its name Sitnah. And he moved from there and dug another well, and they did not quarrel over it. So he called its name Rehoboth, saying, “For now the Lord has made room for us, and we shall be fruitful in the land.”

23 From there he went up to Beersheba.

32 That same day Isaac’s servants came and told him about the well that they had dug and said to him, “We have found water.” He called it Shibah; therefore the name of the city is Beersheba to this day. Gen 26:12-33

Abraham was a well-digger. And he taught his son Isaac to be a well-digger. The key to surviving in the land of Israel is water. Water was the key 3000 years ago, and water is still the key to this day. The location, extraction, and efficient usage of water means the difference between life and death in our homeland. In modern times Israel has become a world leader in its innovative technologies surrounding the efficient usage of water. Israel has partnered with countries in desert regions of Africa, showing them how to turn dry, arid, and unproductive land into gardens and fields full of crops.

So important is water in the Middle East that the decisive battle for control of the Middle East during World War I was over the well of Beersheba, a well that was first dug in this week’s parasha. When the allied forces led by the Australian Light-Horsemen captured the well of Beersheba, they turned the tide of the war against the Ottoman Turks in World War 1.

I have an emotional response to this history because I grew up in rural Australia. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth. I have been present when wells have been dug and water comes gushing forth from the ground below. From the first sign of wet soil to the final gushing of water to the surface, it is mirrored by the welling emotions of hope, exuberance, and finally relief. Relief because our efforts were not in vain. Relief because now we, our loved ones, and our livestock will not starve. Relief because there is hope for a future.

Isaac was a well-digger. Isaac believed in productivity. Isaac was a bringer of hope. Isaac believed in the future.

The Philistines, however, were well-destroyers. In the name of survival, it is understandable that one might capture a well and steal its life-giving water to provide for one’s own tribe. But to fill in a well and to destroy it, thus increasing the likelihood of malnutrition and starvation to one’s own family and tribe, requires a fiendish and perverse ethic. It is one evil to steal wealth. It is another level of evil to simply destroy it.

In Israel, water is wealth. So why did the Philistines fill in the wells?

He had possessions of flocks and herds and many servants, so that the Philistines envied him. Gen 26:14

The Hebrew word for “envied” in this text is not a passive emotion. It is a verb. It describes an envy that turns to anger. The Philistines were angry with Isaac, because Isaac was productive and successful. They were angry with Isaac, because Isaac believed in a future. They were angry with Isaac, because Isaac revived the land, and brought hope to its inhabitants.

There is a lesson to be learned in this interaction, and it is this: There exists a spirit which, against all sound logic, prefers jealousy over cooperation; anger over humility; destruction over productivity. It is a dark and devilish spirit.

The 19th century rabbi Ha’amek Davar, drawing from Midrash Rabbah, explains that this verse is prophetic, foreshadowing the future exiles when Jewish residency rights were restricted, and our success will engender the jealousy of the nations leading to our continual banishment. Moreover, it is not just anti-Jewish to be jealous of success, it is anti-God. To hate wealth and productivity and material success is a form of cultural nihilism that steals the bread from the future generation of children not yet born. To hate productivity is to hate life itself.

But the Jewish spirit is a productive spirit. The Jewish spirit works for the future and believes against all hope that the desert can indeed bloom. The Jewish spirit believes that through the diligent application of hard work in the land where we sojourn, we will not just survive, but we will thrive.

Our Lord Yeshua speaks of this spirit of productivity in expansive terms in the Parable of the Talents. The wicked and unproductive servant describes the Master, allegorically speaking of God, in this way: “Master, I knew you to be a hard man, reaping where you did not sow, and gathering where you scattered no seed.” The Master berates the unproductive servant and says these difficult words: “For to everyone who has will more be given, and he will have an abundance. But from the one who has not, even what he has will be taken away” (Matt 25:29). In other words, the good servant is one who is working, diligent, and productive. Just like Abraham. Just like Isaac.

This is our spiritual heritage. We belong to a long line of hopeful and ambitious men and women who under Gods providential hand have been well-diggers. And just like the Philistines in this parasha, there are always those who hate us precisely because of our productivity.

We must never forget that our productivity is inseparably tied to our holy calling. Our productivity is inseparably tied to the spirit of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Our productivity is inseparably tied the nature of our heavenly Father.

The challenge that we face in Israel today bears the hallmarks of this ancient conflict between Isaac and the Philistines of his day. We Jews are dedicated to digging wells, sowing crops, and living a productive life. Hamas is dedicated to destroying wells, burning crops, and disseminating death. The more we are productive, the more they hate us for it, even if they are the recipients of our abundance.

As I close, I want to leave a note of exhortation to the UMJC community. Be like your forefathers Abraham and Isaac. Dig wells. Plant crops. Work with all diligence. Resist the haters. Believe in the future. Hold fast to hope. Don’t just survive. Thrive!

Taking the Long View

This week’s parasha brings us the account of the very first land purchase in the Land of Promise. Seeking a place to bury his wife, Sarah, Abraham approaches a local landowner to purchase the cave of Machpelah, which was on his property.

Machpelah, Tomb of the Patriarchs, in Hebron

Parashat Chayei Sarah, Genesis 23:1–25:18

Chaim Dauermann, Brooklyn, NY

For the Jewish people, Eretz Yisrael is never far out of mind. This has been especially true in the month since the October 7th massacre perpetrated by Hamas, which took the lives of 1400 people in Israel and led to over 200 hostages being brought into Gaza.

As in past times of conflict in Israel, the validity of Jewish presence in the Land has become a matter of uncomfortable public debate. Many of Israel’s latest detractors may be unaware, or otherwise unwilling to consider, that the Zionist movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was typified not by the “illegal” land grabs they might imagine, but by something far more mundane: land purchases made in full accordance with the law. And it was on the foundation of these land purchases that the Jewish diaspora was regathered in the Land and, eventually the State of Israel was formed.

This week’s parasha brings us the account of the very first land purchase in the Land of Promise. As the portion begins, Sarah has died in Kiriath-arba—or Hebron—near the Oaks of Mamre, where Abraham has been dwelling for some time. Seeking a place to bury his wife, he approaches a local landowner to purchase the cave of Machpelah, which was on his property.

And Ephron the Hittite answered Abraham in the ears of the sons of Heth, all those who enter the gate of his city, saying, “No, my lord, listen to me. The field—I hereby give it to you. Also the cave that is in it—I hereby give it to you. In the eyes of the sons of my people, I hereby give it to you. Bury your dead one.” (Gen 23:10b–11)

Abraham, however, insists upon paying for the field and cave. And when Ephron quotes him a price of 400 shekels, he does not hesitate or bargain. There has been much debate among commentators as to whether this was a good deal. It’s ultimately unclear. But, high price or not, a key thing to note is Abraham’s insistence on paying the full price. By avoiding taking the Machpelah cave and field as a gift, or even at a discount, Abraham helped insure himself against dispute, such as in the event of Ephron’s death. In doing so, he secured a site not only for Sarah’s burial, but also for his own, and for Isaac and Jacob’s after him.

Abraham had his eye fixed on the future. God had already revealed to him that the promise of the Land was a promise deferred:

Then He said to Abram, “Know for certain that your seed will be strangers in a land that is not theirs, and they will be enslaved and oppressed 400 years. . . . Then in the fourth generation they will return here.” (Gen 15:13, 16a)

Abraham knew his own days were numbered. He made his land purchase while looking to a promise he himself would not see fulfilled. He was thinking of the not-yet.

Jewish tradition sees the Machpelah purchase as quite consequential, and many traditions surround its history and meaning. One suggests that the purchase was made in order to inspire the future inheritors of the Land.

The interpretation of Rava is recorded, who states, “It teaches that Caleb separated himself from the counsel of the spies, and went and threw himself upon the graves of the patriarchs. My fathers, cried he, pray for me, that I may escape the counsel of the spies.” (Sotah 34b)

In this telling, the Machpelah site plays a key role in Caleb’s experience as one of the twelve spies to go scout out the land (Num 13). Perhaps it was the knowledge of this ancestral possession that inspired his confidence concerning the Land, even as ten other spies ultimately failed to believe it could be taken.

Abraham’s purchase is not the only instance in Scripture where land is bought as a foundation for promises with a deferred fulfillment. The prophet Jeremiah records that, even as Jerusalem was under siege by the Babylonians—with its destruction and the Captivity imminent—God commanded him to purchase a field in Anathoth, a place only a short distance north of the city. When Jeremiah inquired of the Lord as to why he would command such a purchase at this time, he replied, “Just as I have brought all this great evil on this people, so I will bring on them all the good that I have promised them. So fields will be bought in this land . . . because I will bring them back from exile” (Jer 32:42–43a, 44b).

Elsewhere, we read of King David purchasing (for full price) the threshing floor of Ornan, a place where one day the Temple would stand, although David would not live to see it.

In hindsight, there is a bit of an irony here. Today, the Jewish people are in the Land after the miraculous restorations of 1948 and 1967. All three of these locations, however—Hebron, the site of the ancient city of Anathoth, and the Temple Mount—are currently outside of Israeli control. Just as Abraham, Jeremiah, and David all made their purchases with a long view toward the fulfillment of God’s plans, today the Jewish people continue in a similar not-yet. And as believers in Yeshua, our sense of expectation and eager longing for fulfillment have a scope that is similarly broad.

The author of Hebrews tells us that Abraham has a longer vision than we might understand from the text in Genesis alone. He says that Abraham was “waiting for the city that had foundations, whose architect and builder is God” (Heb 11:10). He later calls this, “The city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem” (12:22). John the Apostle records for us that when Yeshua was preparing his disciples for his departure, he told them he was going to prepare a place where they—and by extension, we—can be with him, a place with “many dwelling places” (John 14:2–3). Later, in Revelation, John gives a glimpse of a “city to come,” saying, “I also saw the holy city—the New Jerusalem—coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband” (Rev 21:2). As for when John’s vision will come to fruition, only God knows. But the witness of Scripture gives us faith in its coming, even if its timing may transcend our earthly lives.

God’s relationship with us has always been built on his faithful nature. He keeps his promises. In times of uncertainty, even (or especially) when we cannot see God’s promise in full, let us, like Abraham, take a long view of God’s redemptive plans. Let us strive to be a Caleb among unfaithful spies.

Meanwhile, let us also pray unceasingly for every hostage’s safe return from Gaza, and for a new and lasting peace in the Land.

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).

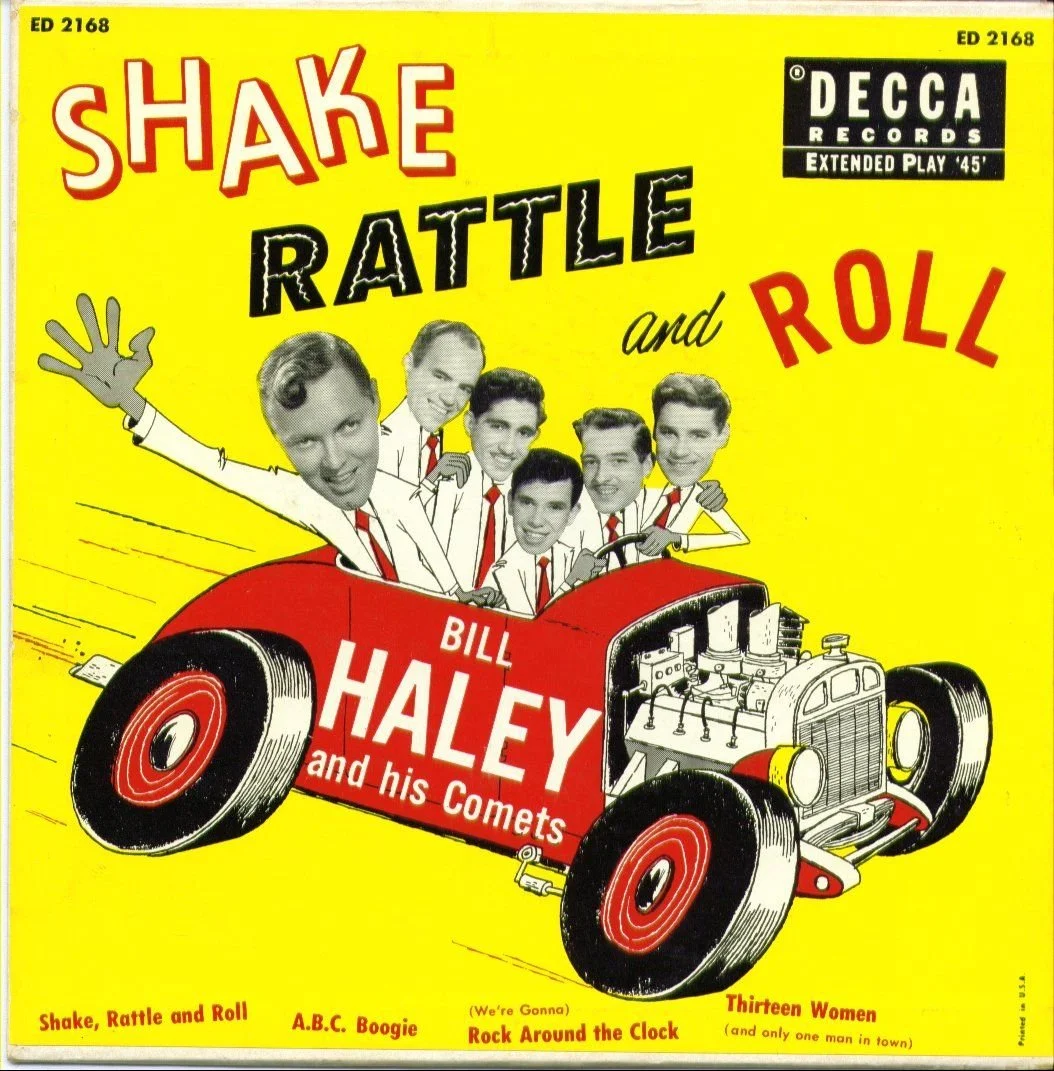

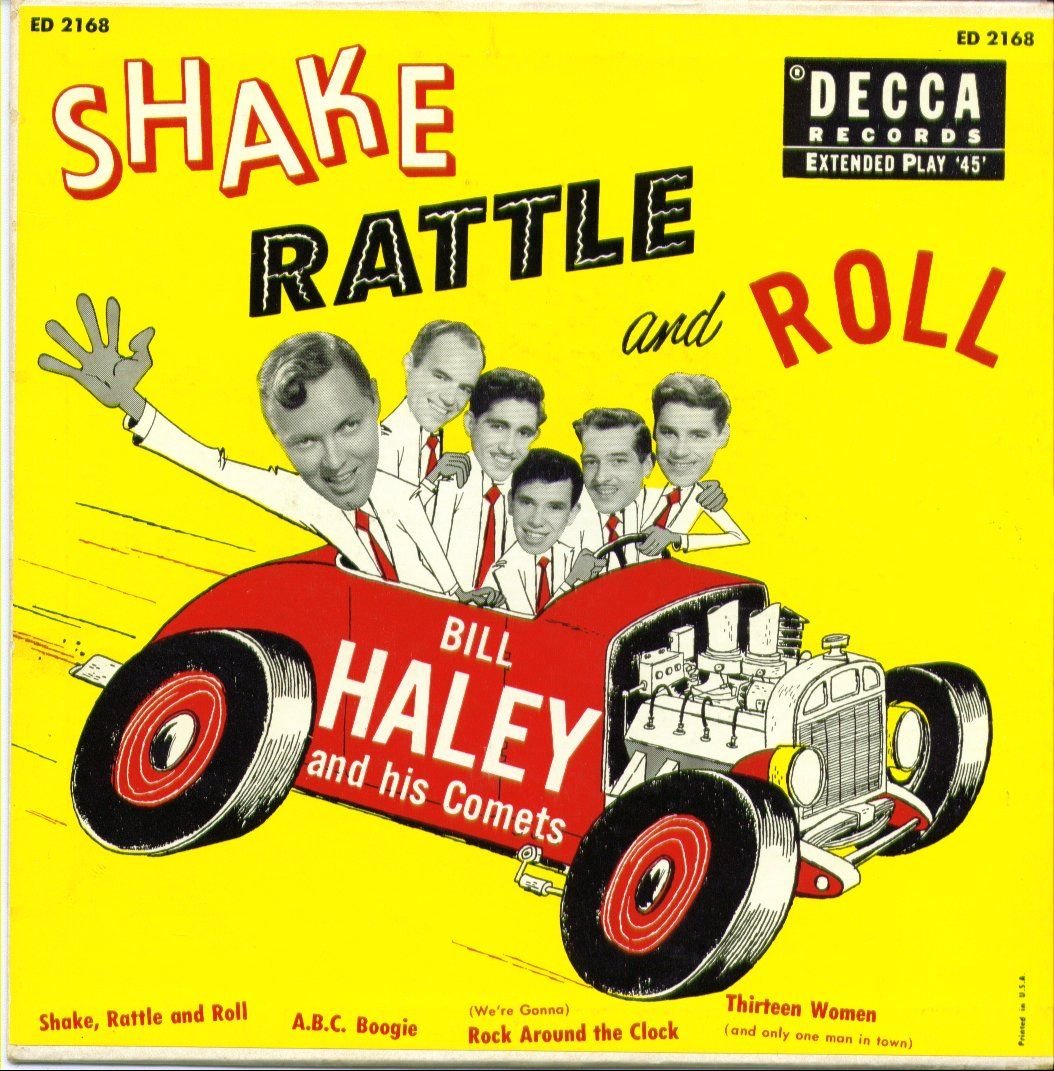

Shake, Rattle, and Roll

The Bible may be the world’s most surprising book. Just when you thought you had God down, you will read something that causes even the dead to rise up and say, “What was that?”

Parashat Vayera, Genesis 18:1–22:24

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann

If the Bible is not a book that surprises you, you are not reading it at all, not paying attention, or simply reading your own views into it.

The Bible may be the world’s most surprising book. Just when you thought you had God down, you will read something that causes even the dead to rise up and say, “What was that?”

This week’s parasha is one of those that just might shake, rattle, and roll the dead, and even some of us.

The first shaker is Avraham fudging on the identity of his wife so as not to tempt the people of the land to take her and knock him off (Gen 20:1–2). I remember discussing this with an Orthodox Jewish airliner seatmate who insisted we should congratulate the patriarch for his cleverness here. I disappointed the man by pointing out how the Torah puts words of moral rebuke into the mouth of pagan king Avimelech, shaming Avraham (Gen 20:9).

This is the second shake-rattle-and-roll in our text: the pagan king as moral arc-light. He is appalled when God tells him Sarah is Avraham’s wife, not his sister. This shaker reminds us of the Book of Jonah, where pagan sailors do everything right while the prophet of God is finding escape routes from doing the will of his Master.

The third resurrecting realization is that even though Abraham is a moral failure in this account, God still considers him a prophet. As a prophet, he has authority to pray, which, when offered, brings healing to Abimelech’s household (Gen 20:7).

What then should we make of these three shakes, rattles, and rolls?

First, we need to reconsider the sharp lines we often draw between God’s good soldiers and “the world.” These lines make for tidy thinking but have little to do with reality. Here in our story, we see the “believer,” the “good guy,” doing the bad things, and the “unbeliever”—the godless pagan—rightly perceiving the still small voice.

We all put some people groups on a pedestal while other we just put down. We make excuses for the ingroup, and make jokes about the others. Our party is the party of God and its platform written on tablets of stone with his finger. The other party has horns and a tail and smells of sulphur. For many people this is the obvious truth, but for a God who looks beyond outward appearances into the hearts of humans, it’s obviously an illusion.

This kind of categorical thinking about religion, politics, and people, is wrong. One way we know it’s wrong is that life is not like that—good people do bad things, bad people do good things, and sometimes it’s impossible to tell the bad guys from the good ones.

When it comes to biased judgments, religious people are well-known offenders, muscular in their judgments, and atrophied in their capacity to criticize themselves or their crowd.

Our parasha chastens and reminds us that sometimes you can’t tell the good guys from the bad guys without a score card, reminding us as well to make sure our score card is the same as the one in the hand of the Holy One.

Anne Lamott warned us: “You can safely assume that you've created God in your own image when it turns out that God hates all the same people you do.” And even though she’s a flaming liberal, she’s got it right, doesn’t she? Imagine that. If you can!

It’s past time to learn our lessons well.

First, we need to learn to not pile on or desert someone who fails to measure up to our image of them. They are not usually bad people. But all of us are a work in process. Let’s offer them a proper measure of support, not too much, not too little, and see what happens. If, instead, we throw stones or turn our backs on them, we sabotage their progress or miss the chance to celebrate their growth.

Yiftach was an illegitimate child whose brothers and the Gileadite elders drove out of town as just so much trash. Years later, when Gilead and all Israel were under attack by the Ammonites, these elders knew enough to send a delegation to recruit Yiftach to help them. He alone had the leadership skills to fight off the enemy (see Shoftim/Judges 11:1–11). Imagine what would have happened if they had simply persisted in writing him off!

Second, we need to learn to not idolize people, putting them on pedestals. Makers of idols are worshipers of lies. When we treat others as icons of perfection, we set ourselves up for disappointment, and them, for a fall. Again, we are all works in process, and our lives are most often two steps forward, one step back, or some variation on the theme. Let’s try to be part of other peoples’ solutions, and not their problems.

Third, we need to realize that everyone is in process. Even giants stumble. And Shorty Zacchaeus became the big guy in town (Luke 19:1–10). Holiness takes practice. Give people space. Yes, even relatives and close friends will disappoint you. But even strangers can astound you in all the best ways. Keep your eyes open, and your heart from being closed.

Avraham only expected unrighteousness from pagans, believing they would kill him to get at his beautiful wife. He was wrong. Some of us may expect nothing good from Democrats, Republicans, Liberals, Conservatives, immigrants, Palestinians, or Muslims. Let’s be careful we don’t make ourselves morally and spiritually blind and deaf.

Nothing I am saying justifies moral relativism. We must never forget this warning, “Oy to those who call evil good and good evil, who present darkness as light and light as darkness, who present bitter as sweet, and sweet as bitter!” (Isaiah 5:20). Evil should never be given the benefit of the doubt.

But neither can we justify being hard-nosed. We all need to seek and be prepared to find the grace, truth, and goodness in the discounted other. Our continual need is balance.

Pray for eyes to see the glimmer of God’s image whenever and however it appears. But don’t go through life with your eyes shut.

Wise as serpents. Harmless as doves.

Shake. Rattle. And roll.

It’s About the People

The events of the last several weeks in Israel have left all of us with a plethora of unchecked emotions. Many of us are experiencing extreme anger, and a cloud of darkness seems to hover forebodingly. In this age, war might be inevitable. Few of us can change the trajectory of violence. But we can decide how we relate to the specter of war.

Playground bomb shelter in Sderot, Israel

Parashat Lech Lecha, Genesis 12:1–17:27

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Congregation Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

In April 2003, on the eve of the Second Gulf War, I attended a forum of four Nobel Peace laureates. Though the United States invasion the next day proved to be misguided, the words of Elie Wiesel that evening stood out to me as an unfortunate truism. No doubt he shared from the perspective of his own experience of World War Two and the ensuing liberation of Holocaust survivors. He stated, “No war is just, but some wars are necessary.” I recall wondering who gets to make such a determination.

The events of the last several weeks in Israel have left all of us with a plethora of unchecked emotions. Many of us are experiencing extreme anger, and a cloud of darkness seems to hover forebodingly. In this age, war might be inevitable. Few of us can change the trajectory of violence. But we can decide how we relate to the specter of war.

This week’s parasha records the call of Abraham, the first Hebrew, and what is understood as the genesis of the Jewish experience. It includes two well-known affirmations—the promise of progeny to Abraham, and the blessing of Abraham by Malchi-Tzedek king of Salem (Gen 14:18–20). But wedged between is a much less-preached story of war that contains important lessons for us. Abram, as he was originally called, allies himself with the kings of Sodom and Gomorrah, as well as other tribal leaders, to liberate his nephew Lot, his family, and their possessions. I suppose there are several lessons we can gain from this terse narrative. But we can learn from at least two things Abraham does right, and one that he could have done better.

Lesson 1—Give God his due (Gen 14:23)

As a reward for not profiteering off the war, and relying upon his God, Abram is rewarded.

Abram said to the king of Sodom, “I raise my hand in oath to Adonai, El Elyon, Creator of heaven and earth. Not a thread or even a sandal strap of all that is yours will I take, so you will not say, ‘I've made Abram rich!’”

According to the sages of the Talmud, Abraham’s descendants are given the mitzvot of the blue thread of tzitzit and the straps of tefillin as a reward for this response (Sotah 17a). By declining the spoils of war, Abraham attributes the victory to God and not his own military prowess. The mitzvot are reminders that the Holy One is always near to his people. It is God who provides and protects.

Lesson 2—Give others their due (14:24)

I claim nothing but what the young men have eaten, and the share of the men who went with me—Aner, Eschol, and Mamre—let them take their share.

Abraham properly repaid those whom he enlisted, and he fed his men adequately. While he refused any bounty from war, he recognized that those who risked their lives defending and liberating his kin were entitled to remuneration and provision.

Lesson 3—Put people first (14:21)

Rabbi Yochanan asks (Nedarim 32a), “Why was Abraham our father punished that his descendants were enslaved in Egypt for 210 years? Because he prevented people from entering under the wings of the Shekinah, that is, from believing in God.” For it says that after the victory over the four kings Abraham returned all captured property, whereupon the king of Sodom said to Abraham, “Give me back the people. You can keep the goods.” Abraham should have insisted on taking the people with him to teach them to believe in God.

Though this is a fanciful accounting derived from Abraham’s silence, it makes a salient point. Perhaps if the people had not returned to Sodom their inevitable fate might have been different when the city was destroyed. It seems right that we answer the divine query by simply assuming we are our brother’s keeper. If we give the Holy One his due, provide for those who protect our freedom, and put people first, perhaps we can find some light amidst the present darkness.

Scripture references are from the Tree of Life Version (TLV).