Finding Our Rosebud

Parashat Vayetze, Genesis 28:10 – 32:3

Rabbi Paul L. Saal, Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

The movie Citizen Kane has been voted by many film academies and publications to be the greatest American movie of all time. Though the film’s cinematography was cutting edge in 1941, it is certainly not up to the technical capabilities of today’s films. Rather, it is the penetrating story that has kept this classic at the top of critics’ lists for more than half a century. Loosely based on the life of William Randolph Hearst, the film is ultimately a searing look into the human desire for love, acceptance, success, and peace.

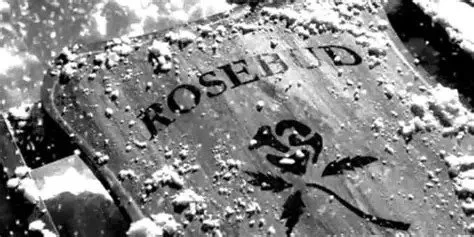

Many are familiar with the famous final word of Citizen Kane: “Rosebud.” In the film, a reporter tries to decode Kane’s entire life through that mysterious word, only to conclude that no single key can explain a human being. But the audience eventually learns that Rosebud was simply the name of Kane’s childhood sled, an emblem of simpler days, a symbol of a time when he knew joy, safety, and belonging.

What makes that symbol powerful is not its sentimental value. It is what it represents: the longing for a spiritual home. A place, internal or external—where we feel rooted, held, and whole. A place we can return to in memory or in faith, especially when life becomes too complicated or burdensome.

This week’s parashah, Vayetze, centers on a figure who desperately needs such a grounding place: Jacob. Jacob is a schemer, a striver, a man who knows how to get what he wants—but always at a price. He outmaneuvers Esau for the birthright, deceives his father for the blessing, and then spends twenty years wrestling with the manipulations of his uncle Laban. His family becomes a source of tension, competition, and heartbreak. And yet Jacob keeps going. Despite the turmoil, he somehow has a center. Something he returns to—his own Rosebud.

That center is Hamakom, literally, “The Place.”

When Jacob flees his home, afraid of Esau and uncertain about his future, the Torah says not that Jacob arrived at a place, but that he encountered Hamakom—the place (Genesis 28:11). It is a complex word, pregnant with potential meaning. The rabbis note that Hamakom is one of the divine names: “the Omnipresent,” the One who is present everywhere yet also meets us somewhere specific, somewhere real and human (B’reishit Rabbah 68:9).

At Hamakom, Jacob dreams of a ladder connecting heaven and earth, with angels ascending and descending. God promises him protection, blessing, and return (28:13–15). Jacob wakes awestruck and declares this place to be “the house of God and the gate of heaven” (28:17). He sets up a pillar, makes a vow, and essentially marks it as the spiritual home he will carry with him.

Jacob’s life from this point forward is not easy. But he has Hamakom, an inner compass point he can return to. When he later says, “God has been with me” (B’reishit 31:5, 35:3) it is probable he is remembering that moment, that place, the foundation that steadied him when everything else shifted.

The Fourth Gospel echoes this story in the encounter between Yeshua and Natan’el (Yochanan 1:43–51). When Yeshua says, “Behold, a true son of Israel in whom there is no deceit,” it recalls Jacob—Israel—whose life was defined by both guile and transformation. When Yeshua adds, “I saw you under the fig tree,” he is drawing on a rabbinic metaphor for studying Torah (e.g., Mishnah Avot 3:7). Many commentators suggest Natan’el had been studying the very story of Jacob at Hamakom. And when Yeshua declares that Natan’el will “see heaven opened and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man,” he identifies himself as Hamakom, he is the point of meeting between heaven and earth, the place where God becomes knowable.

For Jacob, Hamakom became the touchstone that guided him back home. For Natan’el, his encounter with Yeshua became his spiritual grounding. For Kane, Rosebud was the lost memory of a home he never learned to return to.

And for us?

As we approach Thanksgiving, a holiday centered on homecoming, gratitude, and the joy of remembering—we may find ourselves asking similar questions. What is our Hamakom? What is our Rosebud? Where is that literal or spiritual place where we felt truly ourselves, truly connected, truly embraced by something larger than our endless striving?

Thanksgiving invites us to return home, not only geographically, but spiritually. It calls us to give thanks for the moments in our lives when we have and will encounter blessings, connection, and purpose. It reminds us that we are not defined solely by what we accomplish, accumulate, or outmaneuver, but by the places and relationships that root us, shape us, and sustain us.

Jacob eventually returns to the land of his childhood, but more importantly, he returns to the God of Hamakom. He returns to gratitude. To blessing. To the memory of a place where heaven touched earth.

As we gather around tables, travel home, or simply pause to reflect this week, we have the chance to do the same. To remember the moments that formed us. To honor the people who nurtured us. To cherish the encounters, holy or humble, that became our spiritual anchors. And to give thanks for the places, seen and unseen, where the Holy One met us, steadied us, and guided us forward.

May each of us rediscover our Hamakom, our grounding place. May we approach this season not only with gratitude for what we have, but with renewed clarity about where we belong and what truly matters. And may that homecoming, like Jacob’s, strengthen us for the journey still ahead.