commentarY

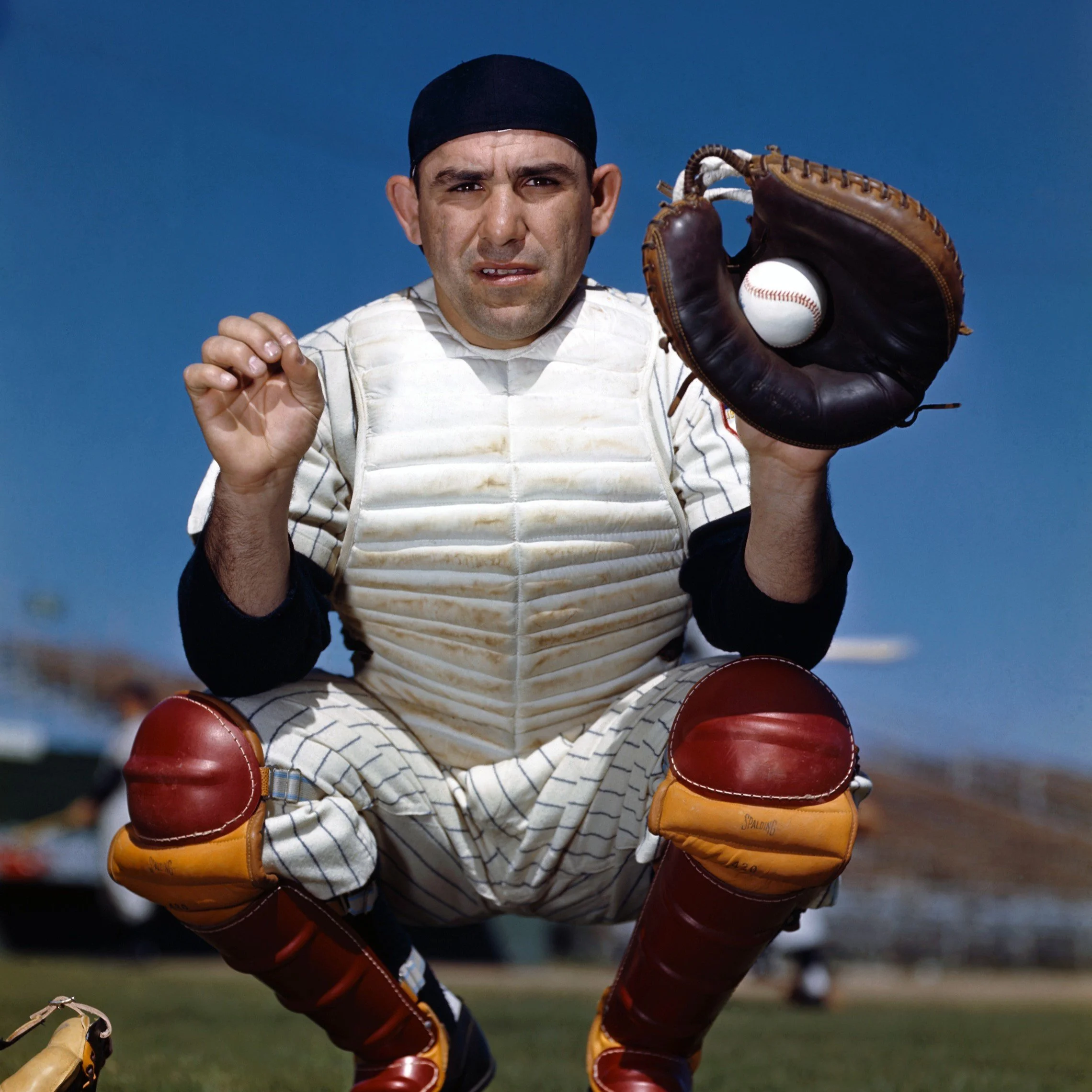

Yogi Berra, Making the Pitch, and Telling Stories

The Prophet Yogi Berra told us, “You can observe a lot by just watching.” Such sage advice! But it is true that we can learn a lot for our own lives by watching how our ancestors lived theirs.

Parashat Sh’mot, Exodus 1:1–6:1

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann, Ahavat Zion Messianic Synagogue, Los Angeles

The Prophet Yogi Berra told us, “You can observe a lot by just watching.” Such sage advice! But it is true that we can learn a lot for our own lives by watching how our ancestors lived theirs.

That’s how it is with a cluster of verses from our parasha where Moshe meets with his brother whom he has not seen in forty years. The encounter is arranged by Adonai himself, and its details outline seven lessons in what it means to share our faith with others.

To learn those lessons, we must travel to Sinai.

Adonai said to Aharon, “Go into the desert to meet Moshe.” He went, met him at the mountain of God and kissed him. Moshe told him everything Adonai had said in sending him, including all the signs he had ordered him to perform. Then Moshe and Aharon went and gathered together all the leaders of the people of Isra’el. Aharon said everything Adonai had told Moshe, who then performed the signs for the people to see. The people believed; when they heard that Adonai had remembered the people of Isra’el and seen how they were oppressed, they bowed their heads and worshipped. (Exod 4:27–31)

What are our lessons in faith-sharing?

Faith-sharing happens within divinely-ordained encounters. God arranged the meeting between Moshe and Aharon. And we should be on the lookout for how God works in our lives to arrange situational set-ups where sharing our faith with others fits the occasion. We might share our faith out of some pervasive anxiety to do so. When we do, the encounter may not be about the one we’re sharing with but about our need to say something. But there are people around us whom God has ripened for our mutual encounter. We should pray for eyes to see and hearts to respond to the occasion.

Faith-sharing best occurs within a prior relationship, as demonstrated by Moshe and Aharon. These relationships may be with family or with friends. Sharing the knowledge of God is highly personal. Little positive and too much negative is accomplished through buttonholing strangers. Look at it this way: sharing the good news of Yeshua is an act of love, an intimate encounter. No matter what our intention, if we ignore this, our faith-sharing may come across not as an act of love, but as an assault. Not good.

But what is faith-sharing? At its root, it is telling stories, the story of Yeshua and the story of our life-renewing encounter with God through him. Patrick Henry Winston, head of the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at M.I.T., taught that what sets humans apart from all other mammals is our capacity to construct and tell stories. If storytelling is central to our humanity, shouldn’t we then share our faith with stories about Yeshua, who he is and what he has done? And shouldn’t we tell our friends stories of our own encounters with him? Yes, we should. That’s what Moshe does here with Aharon, and what he will do later, when he shares his faith with his father-in-law (Exod 18:8–9). Elie Wiesel said that God created people because he loves stories. We should show our love and God’s love to people by storytelling. It’s the human thing to do.

Faith-sharing includes demonstrating the power. People need more than a story. They need to know God is real. Moshe received from God an ability to do miraculous signs. This was a crucial aspect of the storytelling, because the One at the center of the story is a miracle-working God. We can see that this is so by considering the apostles. They lived with Yeshua as his story was unfolding, but that was not enough. When Yeshua asked Peter (Shim‘on Kefa) and the rest of the apostles who they thought he was, “Shim‘on Kefa answered, ‘You are the Mashiach, the Son of the living God.’ ‘Shim‘on Bar-Yochanan,’ Yeshua said to him, ‘how blessed you are! For no human being revealed this to you, no, it was my Father in heaven’” (Matt 16:16–17). Peter knew Yeshua’s developing story, but to come to faith in him, he needed more: he needed to experience the revelatory power of God. So will it be with our friends. This is why we simply must pray for God to show up in the mix, trusting that he can make himself real to the persons with whom we share.

This is a message to be passed down the line. When Moshe and Aharon spoke to the people of Israel, it was Aharon who relayed the story Moshe had told him. This is how faith-sharing happens. One person tells another who then tells others.

This good news fulfills ancient promises. The message Aharon passed on to the oppressed Israelites was no novelty. It was a confirmation of promises made to them long ago. This is why we must share the good news of Adonai’s saving work in Yeshua as something new, which is at the same time linked to ancient words and eternal purposes. It is no gimmick, but the flowering of eternity’s seeds.

Finally, the evidence that the good news we reported takes root in people’s hearts is not simply that they nod their heads in agreement, walk forward, or raise their hands. The evidence includes a new birth of worship that confirms that the Ruach is at work.

Almost sixty years ago, I participated in a panel discussion with the great J. I. Packer, who spoke indelible words I still remember. He said, “Don’t ask me to believe that a person who walks forward at a meeting is a Christian (or, in our terms, a Messianic believer). The evidence of being a child of God is that the person prays and worships God.”

We would do well to think about this, that the new birth is a new birth of worship. This comes from the seed of the word, embodied in the stories we tell.

Shim’on Kefa, Peter, of whom we spoke earlier, put it this way in one of his letters:

You have been born again not from some seed that will decay, but from one that cannot decay, through the living Word of God that lasts forever. For

all humanity is like grass,

all its glory is like a wildflower —

the grass withers, and the flower falls off;

but the Word of Adonai lasts forever.Moreover, this Word is the Good News which has been proclaimed to you. (1 Peter 1:23–24)

Let’s go and tell some stories, sure that the God of Sinai goes with us.

Scripture references are from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

God Already Knows, but He’s Waiting to Hear from Us

God knows all things, but he has assigned to human beings, and therefore to us, a priestly responsibility. Even though our ancestors were groaning under heavy bondage, they still represented God and had the authority to call upon him to intervene.

Parashat Vayechi, Genesis 47:28–50:26

Rabbi Russ Resnik

In the next-to-last scene of the old Star Wars movie, The Empire Strikes Back, the hero, Han Solo, is frozen solid in carbonite by his imperial captors. As he is lowered into a vault, a frosty mist swirls about him and the music fades away. All you can think is, “sequel coming.” It seems like a moment of defeat, but it signals the victory that is sure to come.

Like The Empire Strikes Back, Genesis concludes with an image of seeming defeat—in this case a coffin—that conveys the promise of victory to come. The last two verses read,

Then Yosef took an oath from the sons of Israel: “God will surely remember you, and you are to carry my bones up from here.” So Yosef died at the age of 110, and they embalmed him and put him in a coffin in Egypt. (Gen 50:25–26)

At first glance this seems like a negative ending for the magnificent first book of the Torah. The rabbinic commentators do not say a great deal about it, perhaps reflecting some embarrassment at the fact that Joseph is embalmed, in contradiction to later Jewish law. Christian commentators often see the conclusion of Genesis as negative, suggesting the hopelessness of the human condition apart from divine redemption.

The book of Hebrews however, provides a key to understanding this conclusion: “By trusting, Yosef, near the end of his life, remembered about the Exodus of the people of Israel and gave instructions about what to do with his bones” (11:22).

The coffin in Egypt becomes an emblem of hope, a sure sign that this story is not over yet. Joseph “remembered about the Exodus of the children of Israel” assuring them that God would “surely remember” them and bring them up out of Egypt. God promises redemption, and Joseph believes that promise.

As Genesis concludes, then, we may believe that we have only to wait for the sequel, when the promise will surely be fulfilled. In the Book of Exodus, however, we learn that something else must happen first:

It was, many years later,

the king of Egypt died.

The children of Israel groaned from the servitude,

and they cried out;

and their plea-for-help went up to God from the servitude.

God hearkened to their moaning,

God called-to-mind his covenant with Avraham, with Yitzchak, and with Yaakov,

God saw the Children of Israel,

God knew. (Exodus 2:23–25, Schocken Bible)

The simple language of Torah describes God as taking four actions. The children of Israel groan, and the Lord hears, remembers, looks, and knows. Of course, God knows everything all the time. Hence, numerous translations supplement this final phrase, with words like, “God took notice of them” (JPS, 1967 ed.), or “God acknowledged them” (CJB). But the Hebrew is clear enough: “God knew,” period.

Indeed, God knows all things, but he has assigned to human beings, and therefore to us, a priestly responsibility. Even though our ancestors were groaning under heavy bondage, they still represented God and had the authority to call upon him to intervene on the earthly plane. This is the most basic sense of intercessory prayer. In Exodus, furthermore, we learn that the intervention they called for would involve a struggle against the demonic powers upholding Pharaoh’s dynasty, and holding the Israelites in bondage. As the Lord says, “I will execute judgment against all the gods of Egypt; I am Adonai” (Exod 12:12).

Beyond this basic intercession, we can see a second level, reflected in the traditional prayers that we recite every week. Even after our redemption from Egypt, we remain in exile and bondage, but we can go beyond simple groaning. We have the promise of victory and redemption revealed in Scripture, and can invoke that promise and call upon the Lord to intervene. It’s not clear whether our ancestors in Egypt even remembered the promise of redemption, until Moses came to deliver them, but God heard their anguished groaning. Now, however, we have the assurance of redemption revealed in Scripture, and call upon God on that basis.

Our liturgy is filled with examples of this intercessory outcry. The final line of the Kaddish, also repeated at the end of the Amidah, says, “He who makes peace in the heavenly realms, may he make peace for us and for all Israel.” Peace, the shalom that prevails already in the heavenly court, is central to the prophetic vision of the Age to Come. In the daily prayers, we call on Hashem to establish that shalom in our midst even now. When we sing this prayer, we repeat the refrain, ya’aseh shalom, ya’aseh shalom, shalom alenu v’al kal Yisrael, literally, “He will make peace upon us and upon all Israel,” a prophetic and intercessory cry for the Lord to do what he has promised.

Likewise, before we take the Torah out of the ark, we recite the words, “And it came to pass, whenever the ark went forward, Moses would say, ‘Arise O Lord, and let your enemies be scattered. Let those who hate you flee before you.’” As the word of God goes forth, we pray that the spiritual forces that oppose God and Israel—“the gods of Egypt”—will be defeated and driven back. In this weekly enactment, we are interceding for all Israel, and ultimately for the whole human race, looking forward to the day when “The Torah will go forth from Zion, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.”

With such prayers Israel has taken on its priestly responsibility throughout the centuries, and they remain most valuable in the sight of God. We do well to participate in them, especially as we do so in union with Messiah, who is the true high priest and intercessor. Through him these prayers will be fulfilled in the end, and through him we come to a third level of intercession.

The first level is what we see in the parasha, the simple groaning of Israel, crying out to God for relief. A second level of prayer comes in response to the promises revealed in Scripture. We cry out in the language of divine revelation to remind God to act as he has said he would. The third level is a response to the fulfillment of the promise in Messiah Yeshua. We still await the Age-to-Come, but in Messiah there is a present-day reality, the victory over demonic forces through his death and resurrection, which brings redemption in this age.

God already knows all things, but he’s waiting to hear from us. It is our priestly responsibility to remind him of his promise, and to proclaim the fulfillment of that promise in Messiah Yeshua.

Adapted from Creation to Completion: A Guide to Life’s Journey from the Five Books of Moses, Messianic Jewish Publishers, 2006.

Scripture references, unless noted, are from Complete Jewish Bible (CJB).

Hope Can Set You Free

Who among us hasn’t contemplated revenge? Who hasn’t caught themselves musing at length about toppling an enemy from their pedestal, wanting them to feel for a moment the same pain that they inflicted? When Yosef was hauled off to prison at the whim of Potiphar’s wife, who do you think he blamed?

Parashat Vayigash: Genesis 44:18–47:27

Ben Volman, UMJC Vice President

Who among us hasn’t contemplated revenge? Who hasn’t caught themselves musing at length about toppling an enemy from their pedestal, wanting them to feel for a moment the same pain that they inflicted? When Yosef was hauled off to prison at the whim of Potiphar’s wife, who do you think he blamed? Almost certainly, it would have been those brothers who callously sold him into slavery. After 13 years in Pharaoh’s jail, he had lots of time to imagine how to get even, if he ever got the chance.

As our story opens, it appears nothing can stop him. He’s already played with his brothers’ worst fears and though he’s a stranger, they have come to feel that somehow this Egyptian is an instrument of God’s judgment. They are about to watch him do to Binyamin what they once did to Yosef: make him a slave and send them away to explain the loss to their father.

At this crucial moment, Y’hudah steps forward (Gen 44:18). The Hebrew word “vayigash,” usually translated as “he approached,” carries unusual depths of meaning. One key midrash (Genesis Rabbah 93:6) reminds us that it may be used for entering battle (2 Sam 10:13), to reconcile (Josh 14:6), or to pray (1 Kings 18:36). The word also introduced another timely act of intercession, when Avraham “came forward” to intercede for the righteous who may yet be in Sodom (Gen 18:23).

Y’hudah’s speech is a master class in humility. He makes neither excuses nor any argument to explain or blame. Humbly he lays out the story of his promise to a grieving father, pleading for mercy on behalf of a heartbroken old man. All hope now lies in the hands of Pharaoh’s vizier.

If Yosef had been set on revenge, would this speech have moved him? Perhaps not. But what was in his heart? What happened during those years in prison? We have one important clue: when Pharaoh speaks to Yosef as one with power to interpret dreams, Yosef replies, “It isn’t in me. God will give Pharaoh an answer that will set his mind at peace” (Gen 41:16). This is not the same young man who once boasted of his dreams. These are words of a tested faith worthy of Avraham’s spiritual heir. All his hope is in God and he understands that God draws near to those who know him with shalom shalom, his perfect peace (Isa 26:3).

When I read Anwar Sadat’s memoirs, I was moved by his remarkable account of 31 months spent in a Cairo prison that transformed his life. Conditions in Cell 54 were horrific and disgustingly unsanitary, and prisoners came out for only 15 minutes a day. But in that time, Sadat (only 27 when he entered prison) developed a relationship with his inner self and with his Creator; a loving trust in God that guided the rest of his life. That experience gave him an internal resilience to become the first Arab leader to go to Jerusalem and sign a genuine treaty with Israel.

It’s impossible to know how Yosef found the way to hope and forgiveness in his dungeon. But when he heard Y’hudah’s appeal for mercy, Yosef knew that his brothers were changed. Still, his response came with great pain. Yosef’s long-buried, pent-up emotions overwhelmed him, and he had to order everyone from the room but the captive Hebrews.

Why was it so hard? Until his brothers arrived, Yosef was missing a part of himself. Despite the blessings of God’s presence, he yearned to fulfill his larger purpose as a son of Avraham. God brought his brothers—his betrayers—to restore his lost identity. They alone understood that when he said, “I am Yosef” he was saying, “No matter what you did, you are still my brothers.”

Finally, he could share the profound insight of faith that had given him the freedom to forgive. That is why he immediately declares: “Do not be distressed or reproach yourselves . . . it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you. . . . It was not you who sent me here, but God” (Gen 45:5–8). Yosef may have once wanted revenge, but he had given it up for something greater: he was at peace with God’s gift of a higher purpose.

When I consider how Israel’s future depended on the mercy of a man betrayed by his own brothers looking into the face of the one who sold him into slavery, my old resentments and aging grudges come into painful focus. Yosef spent 13 years in prison—how many years have we locked away some part of ourselves from grace?

One of Elie Wiesel’s German graduate students asked him, “Do you never feel hatred for the German people?” Wiesel replied, “You must turn hatred into something creative, something positive. . . . Express what you feel and let the hate become something else. But do not hate.” After miraculously surviving the Ravensbrück concentration camp, Corrie ten Boom set up a recovery home for fellow survivors. She recalled how those who took hold of life again had hearts to forgive. Those who stayed bitter remained trapped in the past.

We have all gone through waves of trauma over the past three years. I think of dear friends struggling with loss; some who are living with long Covid; others toiling faithfully for the suffering people of the Ukraine. But let’s not lose sight of hope. When Sadat arrived at Ben Gurion airport in November 1977, he had a special greeting for his familiar adversary of the Yom Kippur War, Golda Meir: “I have wanted to meet you for a long time,” Mr. Sadat said. Mrs. Meir replied: “Mr. President, so have I waited a long time to meet you.” He leaned over and kissed her on the cheek.

As the calendar turns over, I can’t think of anything more important than taking hold of hope and the words of Yeshua that lead me to pray: Lord, help me to let go of what needs to be given over to you and to forgive as I’ve been forgiven. Amen and Happy New Year.

All Scriptures are taken from the Complete Jewish Bible.

Light over Might

Let’s make no mistake; the Maccabees did not fight for religious freedom, but to cleanse the land for the worship of the one true God of Israel. While they fought to end the Greek cultic practices imposed through the tyranny of Antiochus, they also fought to end the long-felt effects of assimilation.

Hanukkah 5783

Rabbi Paul Saul, Shuvah Yisrael, West Hartford, CT

One of the primary messages of Hanukkah is to avoid assimilation at all costs. But how often do we hear that the Hanukkah story is about religious freedom? As if any religion would have been OK, so long as everyone got to choose for him or herself. Is that really true? Can we possibly imagine old Mattathias, leader of the Maccabees, accepting a compromise whereby the east wing of the temple would have offered kosher sacrifice, while, in the spirit of pluralism, the Hellenistic Syrians were featuring pork barbeque on the west side?

Let’s make no mistake; the Maccabees did not fight for religious freedom, but to cleanse the land for the worship of the one true God of Israel. While they fought to end the Greek cultic practices imposed through the military tyranny of Antiochus, the Syrian Greek ruler, they also fought to end the long-felt effects of assimilation. The hard-to-swallow truth is that many Jews then, as today, envied the freedom and fanfare of the nations, and were all too happy to put off the yoke of Torah. The war opposed the attractive popular spectacle of uncircumcised Jewish athletes in public sport as much as it did the forced sacrifices to Zeus in the Great Temple. It should not surprise us then that the greatest miracle of Hanukkah is not the immediacy of military triumph, but the sustenance of the divine light.

Perhaps the tradition surrounding how we light the Hanukkah menorah, or hanukkiah, can illuminate (pun intended) this point. One candle is lit the first night with the number of candles increasing each successive night. This is the tradition handed down from the School of Hillel (Shabbat 21b) and accepted by most practicing Jews in the world today. The School of Shammai, in contrast, held that all eight candles should be lit on the first night, and the number of candles should diminish by one each successive night. This view seems logical since each night the sanctified oil used to light the menorah in the Temple would have diminished. But then this would assume that there was enough oil to light the menorah in the first place.

Hillel argues that each night more oil was necessary to light the lamp, so the magnitude of the miracle increased. This follows the Jewish concept of the ascendancy of holiness. Since lighting the Hanukkah candles is a holy act, each night the holiness increases and so therefore should the number of candles.

The two schools of thought punctuate the two-pronged nature of the Hanukkah miracle as identified in the prayer Haneirot Halelu, recited after lighting the menorah each night. The first part states, “these lights we kindle to recall the wondrous triumphs and the miraculous victories wrought through your holy priests for our ancestors in ancient days at this season.” At Hanukkah we acknowledge that God, as is often his style, “gave the strong over into the hands of the weak.” The second part of the prayer goes on to say, “these lights are sacred through all eight days of Hanukkah. We may not put them to ordinary use but are to look upon them and thus be reminded to thank and praise you for the wondrous miracle of our deliverance.” It encourages us to look upon the miracle of maintaining the Jewish people in the face of ongoing assimilationist influences. The real miracle of the lights is that they do not end in eight days; rather, we are encouraged to become participants with God in our own spiritual deliverance by directing our attention to praising him and remembering him as he remembers us.

We might infer that the school of Shammai emphasizes the military victory. Though important, however, the effects of physical victory quickly fade, leaving few lasting results. We have seen this in our own times. How often has the U.S. military machine removed a rogue dictator only to fight the “democratic regime” that succeeds him within a quarter of a century? In the same way, history records that the Maccabees, the so-called champions of religious freedom, became strong-armed dictators of religious oppression in Israel during the century that followed. So by lighting eight candles on the first night and decreasing the number each night after, we observe the diminishing power of military might.

Spiritual power, on the other hand, begins modestly and is often barely noticed, then increases over time and slowly displays its lasting effects. By lighting the candles in ascending order as Hillel suggests, we illuminate (there I go again) the more efficacious nature of the spiritual miracle—the power of the spirit grows day by day.

As it was for the Maccabees, so it is for us. We have a culture that continually attempts to seduce us into believing that true power is in wealth and influence. We American Jews try our hardest to look and act like our neighbors. We crowd the malls this time of year with the same deliberate worship of consumerism as our neighbors, losing the true spiritual meaning of Hanukkah.

But let me not just pick on our Jewish people. What of the Christians across the country who advocate boycotting retail stores unless they put the name Christmas back in their holiday advertisements? I think I missed something here. Shouldn’t believers in Yeshua boycott stores that even imply any connection between the Christ Child and consumerism? After all, wasn’t Yeshua the greatest counter-culturist of them all? When the exuberant crowds called out for a military hero like Judah Maccabee, didn’t he respond by laying down his own life? When Caesar, like Antiochus, sought to grasp divinity and make himself the object of worship, didn’t Yeshua selflessly empty himself into the form of a servant, only to be exalted to the right hand of God on high?

Shouldn’t we then as Messianic Jews during this season become imitators of Yeshua, separating ourselves from the basest tendencies of our culture? Can’t we suffer the indignation of being different from our neighbors for the sake of God’s kingdom? Do we seek after the fading victories of military might and conspicuous wealth, or will we seek God’s higher standards?

This year as we light the menorah on the eighth night of Hanukkah, let’s remember the greatest miracle of the season, that God has sustained his light among his people Israel despite the best efforts of both militant tyrants and seductive assimilationists, recalling the words from the traditional reading for Chanukah: “Not by might nor by power, but by my Spirit, says the Lord of hosts” (Zechariah 4:6).

What Would the Maccabees Do?

When our Gentile friends or co-workers ask us “what’s Hanukkah about, anyway?” we tend to give them sugar-coated references to light, miracles, and funny games with spinning tops. But this is only half of the story.

Hanukkah 5783

Monique B, UMJC Executive Director

Hanukkah begins on Sunday night and lasts eight nights, and this year our very minor Jewish holiday overlaps with a very major Christian holiday. You may have heard of it.

Jewish people have enjoyed a sense of welcome, limited at times, within American society since before our nation’s founding. As a result, we have developed a uniquely American way of celebrating Hanukkah, with eight nights of gifts to our children (to rival the Gentiles’ haul of gifts under their trees), Hanukkah-themed decorations for sale at the local Target or Bed Bath and Beyond, and Chabad-sponsored menorah lightings in our town squares.

When our Gentile friends or co-workers ask us “what’s Hanukkah about, anyway?” we tend to give them sugar-coated references to light, miracles, and funny games with spinning tops. But this is only half of the story.

The full story of Hanukkah must include the catalyst: a tyrant invaded our ancestral land and made our way of life illegal. He offered wealth and power to Jewish priests and landowners, in exchange for tolerating the subjugation of pious Jewish peasants. In so doing, he corrupted our priesthood, paving the way for a complete desecration of our sacred Temple, making it impossible for us to make kosher sacrifices on a tainted altar. Soon his regime outlawed circumcision of infants and the study of our sacred texts. Antiochus’ soldiers occasionally forced random Jewish leaders to make pagan sacrifices in front of their neighbors, a potent humiliation tactic. If his regime had remained for a generation or two, the unique way of life of the Jewish people would have been forever erased. The Messiah would not have come. The nations would still be worshiping rocks and sticks.

Under Antiochus’ regime, many of our people accommodated the new reality for the sake of survival. They pretended to be good pagans in public, and held on to the scraps of Judaism they could still practice in private. But a band of religious zealots planned a rebellion in the caves of Judea, and waged a prolonged campaign of guerilla warfare that finally drove out the occupiers. When we recaptured Jerusalem, we had to immediately contend with our polluted Temple. Before our way of life could be restored, before a single sacrifice could be made on the rebuilt altar, before anyone could seek ritual purification, the eternal flame of the Temple menorah had to be relit. And so it was, and so we endured as a stubbornly resilient people. Foreign empires be damned.

For over two thousand years we have dared to light miniature menorahs and display them outside our homes, not as an act of nostalgia, or an attempt to compete with Santa, but as an act of defiance. Throughout our people’s history we have been beaten down by tyrants who seek our extermination. Every civilization that has sought our destruction has become a memory to be studied in dusty museum archives. But we are still here. The people of Israel live.

As antisemitism rises around the world, it is right for us to remember this era in our people’s history. It is no longer safe to be Jewish in Putin’s Russia—the Jewish community is leaving in droves. On the subways and streets of New York City, Jewish people are attacked once every 16 hours. In the last few weeks, those attacks have increased in ferocity and in frequency, inspired by Kanye West and Kyrie Irving’s endorsements of Black Hebrew Israelite ideology—which preaches that the “real” Jews are black Africans, and that we are the fakers. On the airwaves, and on social media platforms like Twitter, Telegram, Gab, and Truth Social, antisemitism and Holocaust denial are trending.

Everywhere that Jewish people have ever gone, in every society where we have sought asylum, the welcome mat has eventually been pulled. We are too strange and too stubborn to fit into Gentile societies—this was true for our patriarchs and matriarchs, for Moses, Daniel, Esther, and the Maccabees. It is still true today. Our very identity predates the concepts of race, religion, and nationality. So we are eternally treated as a “problem” to be solved. And our enduring survival in spite of everything they have thrown at us aggravates our haters even more.

What are we to do, as Messianic Jews living in 21st century America, when antisemitism is trending? We tread on especially treacherous ground, because some antisemites call themselves Christians, and for them, we are the only “acceptable” kinds of Jewish people, due to our fidelity to Yeshua. Sometimes they visit our synagogues, pray alongside us in our pews. If they stick around long enough, they inevitably heckle and pester us about our unique mission. “It’s too Jewish,” they say. “Too Jewish,” like that’s a bad thing. “Too Jewish,” as if it’s ever remotely possible for a synagogue, of all places, to be too Jewish.

What should we do when we face people like this? How do we discern our friends from our foes in such a turbulent environment? Should we serve as tokens for antisemites who call themselves Christians, enjoying a limited sense of elevated status in their midst? Should we depend on their donations and make excuses for their ignorance? Or do we have a special duty to correct their skewed perspective, and call them to make teshuva?

If our community is going to stand for anything, if it is going to mean anything in the broad scope of human history, and in the kingdom of heaven, let it be this: that it is entirely impossible to follow the Messiah of Israel while harboring resentment, envy, or hatred for the people of Israel. If we are going to be known for anything, it should be for making our homes, our neighborhoods, even our workplaces, more Jewish than we found them.

As you light your Hanukkiah this weekend, place it proudly in your windowsill. When your neighbors ask, “What’s Hanukkah all about anyway?” tell them that a tyrant invaded our ancestral land and tried to make our way of life illegal. We drove him out, and he met the same fate as everyone across history who has sought our destruction. We’re lighting these candles to thank the God of Israel for the miraculous and enduring survival of the people of Israel. Our people have walked through endless trials, and we’re still here. If that’s not abundant evidence for the existence of God, then nothing is.

As we add to our daily prayers during the week of Hanukkah:

You delivered the mighty into the hands of the weak, the many into the hands of the few, the impure into the hands of the pure, the wicked into the hands of the righteous, and the degenerates into the hands of those who cling to your Torah. And you made for yourself a great and holy name in your world, and performed a great salvation and miracle for your people Israel, as you do today.

“Turned into Another Man”

A little old Jewish lady decides to make the long journey to speak with a holy man in India. When she arrives, his attendants turn her down—the guru is thronged by admirers—but she is so insistent that they finally let her in on one condition: she can only speak three words.

Baba Ramdev, Photo by Sam Panthaky/AFP.

Parashat Vayishlach, Genesis 32:4–36:43

Rabbi Russ Resnik

A little old Jewish lady decides to make the long journey to speak with a holy man in India. She flies into New Delhi and takes a train to a small town in the mountains, where she catches a rickety old bus for another leg of the journey. At the end of the bus line, she hires a porter to schlep her bags as she walks the last few miles. Finally, she arrives at the ashram and demands to speak with the guru right away. His attendants turn her down—the guru is thronged by admirers—but she is so insistent that they finally let her in on one condition: she can only speak three words. “Fine,” says the old lady. When she comes before the holy man, she looks up at him and says, “Sheldon, come home!”

People of all sorts long to escape the commonplace and be transformed into someone more holy. What they often discover, however, is that such a change can only come from an encounter with something—or someone—beyond themselves. The Torah speaks of just such encounters.

Thus, our last parasha opened with Jacob departing from the land of promise. As night falls, the text says literally, “he encountered the place” (vayifga bamakom; Gen 28:11). Jacob spends the night in that place and has a vision of a ladder joining heaven and earth. He recognizes that in reality he has encountered God, sometimes named in rabbinic literature as HaMakom, or the Place. This encounter with HaMakom prepares Jacob for the journey that lies before him. At the end of the parasha, as Jacob is about to return to the land, we see the same verb: “And angels of God encountered him” (Gen 32:2). Now he will be prepared to return to the land from which he departed decades before.

“Encounter” in these contexts implies something out of the ordinary, the heavenly realm breaking into the earthly. Jacob is not equipped for his departure or his return without this heavenly breakthrough.

We see the same verb in the story of King Saul. Samuel anoints him as king and sends him back to his father’s house to await the time of his public revelation. Samuel tells Saul that he will “encounter a band of prophets . . . Then the Spirit of the Lord will come upon you, and you will prophesy with them and be turned into another man” (1 Sam 10:5–6).

“Turned into another man . . .”—this is the appeal of Jacob’s story. We might believe there is a transformed world waiting, the restored Creation of which the Scriptures speak. But like Jacob—and Sheldon—we desire transformation for ourselves. In the end, we learn that only a divine encounter will make us different people.

More than the other patriarchs, Abraham and Isaac, Jacob is like us. Abraham, despite the flaws that Genesis honestly reports, appears on the scene as a visionary from the very first, a pioneer of faith in the one true God. Isaac is more passive, but he never veers from the faith of his father Abraham. Jacob, in contrast, is the patriarch with whom we can most identify, the Everyman of Genesis. Like us, he is a person in process. His potential for greatness is evident, but nearly always mixed with qualities that are more ordinary.

Thus, for example, Jacob has the greatness to recognize and desire the spiritual legacy of his father Isaac, unlike his brother Esau who despises his birthright (Gen 25:34). But he gains the birthright ignobly, taking advantage of Esau’s shortsightedness to buy it for a bowl of lentil stew, and colluding with his mother’s deception to gain Isaac’s blessing. It will take twenty-two years serving the wily Laban to transform Jacob into the man who can return to the Promised Land and take up the legacy of his forefathers. We may sympathize with his trials at the hand of Laban, but we realize that they are necessary—just like the trials that mold us.

In Parashat Vayishlach, however, we learn that such trials do not give the final shape to Jacob, but the divine encounters do. This parasha is a tale of homecoming. Jacob discovers that you can come home again, but you cannot come home unchanged. The Jacob who returns is different from the Jacob who departed:

So Jacob remained all by himself. Then a man wrestled with him until the break of dawn. When He saw that He had not overcome him, He struck the socket of his hip, so He dislocated the socket of Jacob’s hip when He wrestled with him. Then He said, “Let Me go, for the dawn has broken.”

But he said, “I won’t let You go unless You bless me.”

Then He said to him, “What is your name?”

“Jacob,” he said.

Then He said, “Your name will no longer be Jacob, but rather Israel, for you have struggled with God and with men, and you have overcome.” (Gen 32:25–29 TLV)

Jacob undergoes two changes on his way home. His hip joint is dislocated, and his name is changed. Over the centuries commentators have discussed whether Jacob’s injury is permanent, but it’s clear that God touched Jacob and left a mark on his soul that he would never forget.

Jacob’s renaming has also evoked endless discussion, along with a variety of different translations, such as that of Everett Fox:

Then he said:

Not as Yaakov/Heel-Sneak shall your name be henceforth uttered,

but rather as Yisrael/God-Fighter,

for you have fought with God and men

and have prevailed. (Gen 32:29)

Likewise, Ramban (Nachmanides) sees Jacob’s new name as the opposite of his old one:

Thus the name Ya’akov, an expression of guile or of deviousness, was changed to Israel [from the word sar (prince)] and they called him Yeshurun from the expression wholehearted ‘v’yashar’ (and upright).

Jacob’s new name, like his injury, proclaims the transforming encounter with the divine. Jacob experiences two encounters—one as a young man setting out on his journey with nothing, and one as a mature man surrounded by possessions and cares, dependents and responsibilities. Apparently, the transforming encounter is not only for the young and adventurous, but also for the middle-aged (or beyond) and established. Whether we are caught up in youthful self-absorption or in the complacency of mature age, only a touch from God will really change us.

“Turned into another man.” The earliest stories of Genesis hint at the hope of new birth that is central to the work of Messiah and the writings of the New Covenant millennia later. Jacob is the Everyman of Genesis, and his story reminds us that we all must be changed by a divine encounter to find our place in the renewed Creation. Our Messiah taught, “Amen, amen I tell you, unless one is born from above, he cannot see the kingdom of God” (John 3:3 TLV). And Jacob’s story reminds us that this new birth is not a one-time encounter, but one that is to be renewed throughout our lives.

Only an encounter with God can bring the transformation that prepares us for a lifetime of faithfulness. May we remain open to divine encounters that may await us, and may we embrace them as essential stages of our journey.

Adapted from Creation to Completion: A Guide to Life’s Journey from the Five Books of Moses, Messianic Jewish Publishers, 2006.

Making Peace with an Intimate Enemy

Genesis is irreplaceable, forming a sturdy foundation for all of Scripture and all of life. Its portraits of family dysfunctionality provide a master class in ineffective and effective conflict resolution.

Parashat Vayetse, B’reisheet/Genesis 28:10–32:3

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann, Ahavat Zion, Los Angeles

Genesis is irreplaceable, forming a sturdy foundation for all of Scripture and all of life.

Its portraits of family dysfunctionality provide a master class in ineffective and effective conflict resolution. Because the conflicts in Genesis find their counterparts in our lives, we do well to learn its lessons.

This week’s parasha focuses on Ya’akov’s conflicts with his uncle and father-in-law, Lavan (or Laban). Rabbi Lilly Kaufman deftly sketches this messy family constellation:

Poor Jacob is triply triangulated in Parashat Vayetzei! His boss, Laban, is not only his uncle, (his mother Rebecca’s older brother), but also Jacob’s father-in-law, Leah and Rachel’s father. Leah and Rachel are bitter rivals, Leah resenting Jacob’s love for Rachel, and Rachel wishing for children when God has blessed only Leah with fertility. Complicating this tangle of relationships is the fact that Jacob and Laban work together, and Laban is not a fair employer.

Judging Lavan to be unfair is too generous. He is actually a manipulative victimizing narcissist. He sells both his daughters into marriage to Ya’akov for the exorbitant price of seven years labor for each. And he foists one of those daughters on Ya’akov by pulling a switch in the dark, passing Leah to Ya’akov for a sexual union which will render them married. However, Ya’akov thought he was getting his beloved Rachel as a bride. Thus Lavan misused both daughters plus his son-in-law. He also cheats his son-in-law every chance he gets.

Amazingly, nowhere in Torah’s account of twenty years of his dealings does Lavan admit wrongdoing. Instead, he unfailingly deflects all blame and responsibility onto others in the family. Ya’akov and his wives would be quick to tell you Lavan is no prize.

Finally, after twenty years of abuse, including being cheated of fair wages by Lavan, Ya’akov has had enough. God tells him it’s time to pick up and leave Paddan-Aram to go home to Canaan.

He departs with his wives, his children, his livestock, and whatever riches he had gathered. Meanwhile, Lavan is some distance away from home. It’s sheep-shearing season. Three days after Ya’akov heads west, Lavan hears he is gone and takes after him. It takes him a week to catch up with Ya’akov in the hill country of Gil’ad.

What happens next provides us an excellent model for conflict resolution.

The first step of the model is the presentation of grievances, which each man does in turn. Lavan speaks first, complaining that Ya’akov took off in the middle of the night, with all he owned, and also his wives, daughters of Lavan, and his children, Lavan’s grandchildren. Lavan presents himself as betrayed and innocent.

Next, it is Ya’akov’s turn. He recounts all the trouble he has endured, twenty years of it, point-by-point. He summarizes it all:

These twenty years I’ve been in your house—I served you fourteen years for your two daughters and six years for your flock, and you changed my wages ten times! If the God of my father, the God of Avraham, the one whom Yitz’chak fears, had not been on my side, by now you would certainly have already sent me away with nothing! God has seen how distressed I’ve been and how hard I’ve worked. (B’reisheet/Genesis 31:41–42)

Lavan denies all guilt, again identifying himself as the wronged party who did nothing wrong,

This brings us to our second step. In such a conflict, it is important that neither side be shamed, even if they are offering a self-serving and even patently false version of the events. They should be allowed to protect their dignity and image. There is nothing to be gained and much to be lost by exacting a pound of flesh at such times. Lavan has to portray himself as guiltless and wronged. It is psychologically impossible for him to do otherwise. Do you know anyone like that? I think we all do!

Then comes the third step, the litigants must choose to look away from the present and the past toward a desirable future. Lavan suggests he and Ya’akov assemble a standing stone, to which Ya’akov adds more stones.

Lavan says,

“May this pile be a witness, and may the standing-stone be a witness, that I will not pass beyond this pile to you, and you will not pass beyond this pile and this standing-stone to me, to cause harm. May the God of Avraham and also the god of Nachor, the god of their father, judge between us.” But Ya‘akov swore by the One his father Yitz’chak feared. Ya‘akov offered a sacrifice on the mountain and invited his kinsmen to the meal. They ate the food and spent the whole night on the mountain. (B’reisheet/Genesis 31:52–54)

The stone marker and the meal eaten together seal a covenant between these men to work toward a better future together.

In her drash on this parasha, Rabbi Kaufman points to a further step in peace-making. We will all agree her observation matches our experience.

This step recognizes how sometimes there are toxic people from whom we should separate ourselves. This is what Laban and Ya’akov do. They make their covenant, but they also agree to remain separated.

Rabbi Kaufman puts it this way:

It may surprise some readers of the Bible that family separation is employed as the problem-solving strategy in the Jacob-Laban story. In fact, it is a common technique of dispute resolution in early chapters of the Bible. In Lekh Lekha (Gen. 13:1–13), Abram separated from Lot, his nephew and sole heir, after their dispute over grazing land, but their real clash was over conflicting values. At stake was the future of their family’s spiritual commitments: to worship God, as Abram wished, or to incline towards Sodom and Egypt, as Lot did. In Vayetzei, as in Lekh Lekha, the biblical hero is much better off putting distance between himself and a toxic family member who does not share his values.

Sometimes we must take such measures if we wish to truly preserve peace and our own sanity.

Shabbat Shalom

Scripture references are CJB. Visit Rabbi Kaufman’s drash at https://www.jtsa.edu/torah/escaping-a-toxic-relationship/

Two Sons, Two Ways of Life

Do you ever feel as if your life is a conflict between good and evil? Rebekah, Isaac’s wife, was pregnant with twins, but the twins struggled within her, causing her great distress. When she inquired of the Lord, he answered her, “There are two nations in your womb.”

Parashat Toldot, Genesis 25:19–28:9

Daniel Nessim, Kehillath Tsion, Vancouver, BC

Do you ever feel as if your life is a conflict between good and evil?

Rebekah, Isaac’s wife, was pregnant with twins, but the twins struggled within her, causing her great distress. When she inquired of the Lord, he answered her, “There are two nations in your womb. From birth they will be two rival peoples. One of these peoples will be stronger than the other, and the older will serve the younger” (Gen 25:23, CJB).

In fact, these two children of hers would not only be rivals in terms of their relationship to the God of Abraham and Isaac; their lives would take completely different trajectories.

One would go east. One would make the Land of Promise his home.

One would take wives of the sons of Heth, the other would take his wives from his own God-fearing family.

One would be a hunter accustomed to killing wildlife for food, the other would be a pure, quiet man, living in the family encampment.

One would despise the birthright, the other would crave it.

One would be hated by God, the other would be beloved.

One was on the path of wickedness, the other of righteousness.

The two would have very different destinies, but paradoxically their destinies would always be intertwined. While the two kingdoms of Esau and Jacob were to be completely separate, they would yet have a lot to do with one another. Like it or not, their destinies were entwined, just as our present existence is intertwined with evil. It is telling that the biblical account never tells us whether they met up again after their father’s burial (Gen 35:29). Their ongoing relationship is left untold.

This is a recurring pattern in the Torah. It had already occurred with Jacob’s grandfather, Abraham, who had parted ways with his nephew Lot. Abraham would hold on to the promise and remain in the Promised Land. Lot would go east, back in the direction of the land which his family had been called from. No good could come of that. Abraham and Lot’s descendants would thereafter have a conflictual relationship. Their destinies were entwined.

So often in life, we find ourselves entwined with the evil prevalent in our world. Perhaps we are employed in a company that has some unethical practices going on. Perhaps we are governed by unethical rulers, to whom we pay our taxes. Perhaps we find that there are things in our very own lives that we are unable to free ourselves from.

We might wish that we could live entirely on a different plane. We might wish that we could be completely done with the wickedness of the world. After all, we have heard Moses’ call to Israel in Deut 30:19: “I have presented you with life and death, the blessing and the curse. Therefore, choose life, so that you will live, you and your descendants.” We have presumably made the choice for life, to live within our covenantal relationship with God, and everything that implies, including accepting his Anointed One. But somehow we find that we are unable to live that “pure and spotless” life that we have chosen.

The fact is that we live our lives in a world that is frightfully damaged by Esau, an Esau that we cannot completely disengage from. Nor would we want to, because Esau is indeed our flesh and blood and we love him. Because we care for Esau, we endure pain. Perhaps the greatest example of this is our Messiah himself, who was described as a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief (Isa 53:3). We see that Yeshua, too, was not unaffected by the evils of our world.

Can we free ourselves from the entanglement of evil?

The key is all in the choice that we have made, and the trajectory that we have chosen.

Some have chosen a trajectory that leads eastwards, towards the lands of idolatry. There is no hint that either Esau or Lot had to make the choices that they did. When Esau chose to sell his birthright, and then in false outrage threatened to kill his brother who went to claim it, he made choices. When he chose to marry women from the children of Heth rather than from a godly family, he made choices. When he chose to move eastward, his ongoing choices were actually signs of the trajectory that he had chosen. The same goes for Lot.

We certainly have a choice. It is a choice mandated to us in the words of Moses: “choose life, so that you will live.” We are in fact commanded to make the choice for life. It is a choice that is stark. A choice between two polar opposites. As Moses put it, a choice between blessing and curse, between life and death.

It was not just in Moses’ era. Sometime in the fist century CE, Jewish disciples of the Apostles wrote a letter to the gentile groups and congregations springing up all over the region. This discipleship manual, the Didache, says right at the beginning, “the difference is great between the two ways.” The difference is indeed great. It is the difference between light and darkness, as others would put it.

What makes the difference between the two ways is where they each lead. They begin as a choice, a choice at the crossroads if you will. That doesn’t mean that there won’t be problems along the way. After Israel made the choice for life the Hebrew Bible contains a remarkable catalogue of both successes and failures. Entanglements with idolatry, entanglements with greed at the expense of the poor, for example. Following the days of Yeshua, the New Covenant also contains a striking picture of communities in some ways commendable but in other ways subject to appalling shortcomings. Strife, division, idolatry, and immorality are common issues the writers had to address.

So where does our choice of the way of life lead to? It does indeed increasingly remove us from the entanglements of the way of death.

How does this happen? How can we be sure of our destination?

Israel provides a helpful example, despite Israel’s failings to consistently follow through on the choice made before Moses.

In Jeremiah 31:35 the prophet makes a remarkable statement. It is based in part on Moses’ proclamation to Israel in Deuteronomy when he commanded them to make the choice of life, with heaven and earth standing as witnesses. In Jeremiah 31:35 the Lord speaks as the one who made the heavens and the earth. He is the one who “gives the sun as light for the day, who ordained the laws for the moon and stars to provide light for the night.” He also speaks as the one who made the earth. So, we are told that he is the one “who stirs up the sea until its waves roar.” Before these same witnesses of the heavens and the earth, it is the Lord who ensures that his covenant relationship with Israel is upheld. It should be no surprise that the New Covenant carries this theme forward for all who have made the choice to worship the God of Israel in the name of his Son.

It is thus that ultimately the faithfulness of the Lord is what gives us hope. We have made our choice for life. None of us have been completely consistent in following through. But there will come a time when we will be freed from those entanglements that would seek to drag us onto the way of death.

In Ein Yaakov, commenting on b. Avodah Zarah 1.17, there is the saying, “It is customary with a human king that while he is within the palace his servants guard him from without. With the Holy One, praised be he! it is the contrary. His servants are inside, and he guards them from without.” Thus is borne out the Scriptural message that it is not we alone who can free ourselves from the entanglements of the world, even by making that choice for life. Ultimately, it is the Kadosh, Baruch Hu, the Holy One, blessed be he.

It’s a Family Thing

I’m about to be a father for the first time. Our son will be born quite soon. This impending change brings a heavy feeling with it, though not a burdensome one. Lately, I’ve found myself looking at life in new ways.

Parashat Chayei Sarah, Genesis 23:1-25:18

Chaim Dauermann — Congregation Simchat Yisrael, West Haven, CT

I’m about to be a father for the first time. Our son will be born quite soon. This impending change brings a heavy feeling with it, though not a burdensome one. Sometimes I am awake late at night, with nothing but the occasional Brooklyn traffic to break the silence, and it is in such times that I can most effectively take stock of my reality.

Lately, I’ve found myself looking at life in new ways. Before, I saw my physical, mortal life as something finite that would be someday transcended, but now I find myself seeing it as something I tangible that will continue beyond me in the form of a family. My wife and I will work to impart to our son the very best of what we have to offer as people, and somehow, if all goes well, in him those things will make their way in the world long after we are gone. And what we have within us to give him represents the best of what our parents and forebears were. In this way, as I invest the best of myself in my son in an effort to fulfill my duty as a father, I will also be further stepping into my role as a son.

In ruminating on these things, I’m entering a very Jewish conversation. The phrase l’dor v’dor—from generation to generation—encompasses this idea perfectly; it reflects a continuum of knowledge and experience, the passing of Jewish tradition and values down through the ages. The key mechanism in this process is family.

The parasha for the week is Chayei Sarah, which means “the life of Sarah.” It seems ironic, at first, given that the portion actually begins with Sarah’s death:

Sarah lived 127 years; these were the years of the life of Sarah. And Sarah died at Kiriath-arba (that is, Hebron) in the land of Canaan, and Abraham went in to mourn for Sarah and to weep for her. Genesis 23:1–2 ESV

But in a sense “the life of Sarah” is a perfectly appropriate name for this parasha. For indeed, only a generation prior to this passage, Sarah and Abraham had looked to the future with no prospects for descendants—the end of the line when it came to Abraham’s bloodline. Yet, through God’s promise to make of Abraham a great nation (Gen 12:2) and through his miraculous intervention, Sarah would conceive a son, Isaac, when it seemed altogether impossible, and through him her descendants turned out to be many, indeed.

But how do these descendants come about? How does this great nation rise up from Abraham and Sarah, through Isaac? In Genesis 24, we read of Abraham giving instructions to his trusted servant to return to his home country to find a wife for Sarah’s son, Isaac, ensuring that not only his own family, but an entire nation would live. We often hear this servant referred to as “the faithful servant,” and Jewish tradition identifies him as Eliezer of Damascus. Eliezer rates but one mention by name in the Torah, in Genesis 15:2, but his reputation looms large in Jewish tradition. So large, in fact, that the sages identity Eliezer along with the likes of Elijah as one of eight people who they say ascended to heaven without dying (Derech Eretz Zuta 1:18).

In sending out Eliezer to seek a wife for Isaac, Abraham connects the task with the covenant God made with him: “To your offspring I will give this land” (Gen 24:7). He knows that the land promise that God made cannot come to pass unless he has descendants beyond Isaac. As he invokes God’s covenant, he tells Eliezer that the angel of the Lord will go ahead of him, and help identify the right woman to be Isaac’s wife.

That brings us to this question: What is it that made Eliezer “faithful” in the eyes of tradition? Surely, he had walked with Abraham long enough to know that God could do whatever he purposed to do. Scripture records that he prayed to God upon arriving at his destination, and that he offered up a prayer of thanks upon finding Rebekah. As he trusted in God’s power, however, Eliezer did not rest on his laurels, waiting for the angel of the Lord to do the work for him. Rather, he went about his search thoughtfully and actively. Upon meeting Rebekah, he gave gifts to her and her family. He was prepared for the task, and dealt with it with deliberate care.

The Brit Chadashah has quite a bit to say on the subject of Abraham’s offspring, and on faithfulness. In chapter 3 of both Luke and Matthew, we read of Yochanan the Immerser admonishing the Pharisees and Sadducees for presuming that because they are Abraham’s offspring, they can enjoy the benefits of his immersion without repentance. He tells them, “God is able from these stones to raise up children for Abraham” (Matt 3:9 ESV). That is not to say that this is what God would do, but what God could do if he couldn’t count on participation. Here, Yochanan calls the Pharisees and Sadducees, and us as well, to a high standard.

So, what does it mean to be a child of Abraham? What conduct is befitting of one who would call Abraham “father?” Paul speaks to this quite a bit in his writings, and with a particular eloquence in his letter to the Romans, in which he paints a detailed portrait of the sort of life we are called to as followers of Messiah. On the topic of being children of Abraham, Paul writes:

That is why it depends on faith, in order that the promise may rest on grace and be guaranteed to all his offspring—not only to the adherent of the law but also to the one who shares the faith of Abraham, who is the father of us all. . . . No unbelief made him waver concerning the promise of God, but he grew strong in his faith as he gave glory to God, fully convinced that God was able to do what he had promised. That is why his faith was “counted to him as righteousness.” Romans 4:16, 20–22 ESV

But what does it look like to share the faith of Abraham, as Paul describes here? Chapters 12-14 of Romans are largely dedicated to explaining what a life of faith entails. Following this section, Paul looks to Yeshua as the greatest example of this faithfulness:

Therefore accept one another just as Messiah also accepted you, to the glory of God. For I declare that Messiah has become a servant to the circumcised for the sake of God’s truth, in order to confirm the promises given to the patriarchs and for the Gentiles to glorify God for his mercy. Romans 15:7-9a TLV

During my late nights, when I quietly contemplate my unborn son’s upbringing, my thoughts are in no way anxious, but are happy ones. As I think on the exchange of responsibilities and experiences that my son, my wife, and I will have with one another, and with generations past and future, I settle into the same conclusions that I am coming to here about this week’s parasha. It is by living faithfully, and teaching others to do the same, that we, like Eliezer, make the way for Abraham’s offspring. It is by trusting in God’s power, and by living in subjection to that power, that we ensure that the life of Sarah can continue, from generation to generation.

Greeting God the Unexpected Guest

The Almighty visits Abraham at the oaks of Mamre to show us how to care for the sick among us, those who are ill in body and soul, just as he provides the example of caring for the impoverished and vulnerable.

Parashat Vayera, Genesis 18:1–22:24

Rabbi Russ Resnik

And the Lord appeared to Abraham by the oaks of Mamre, as he sat at the door of his tent in the heat of the day. He lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold, three men were standing in front of him. (Gen 18:1–2)

One key to impact and influence in life is: “Don’t just say it; do it.” Don’t just lecture about your beliefs and convictions; act them out. Or more simply, “Don’t just talk the talk; walk the walk!” It’s especially true in seeking to instruct and influence younger people; they’re looking more for exemplars than explainers.

A famous discussion captured in the Talmud imagines how the Almighty might apply this principle to himself. It’s based on an imaginative reading of the opening lines of our parasha.

One of our ancient sages, Rav Hama, asks, What does it mean, “You shall walk after the Lord your God”? (Deut 13:5). Is it possible for a person to walk and follow in God’s presence? Does not the Torah also say “For the Lord your God is a consuming fire”? (Deut 4:24). But it means to walk after the attributes of the Holy One, Blessed be He. As He clothes the naked—for it is written: And the Lord God made for Adam and for his wife coats of skin, and clothed them—so you also shall clothe the naked. The Holy One, Blessed be He, visits the ill, as it says, “And the Lord appeared to him by the oaks of Mamre” (Gen 18:1)—so you shall visit the ill. (b.Sotah 14a)

Rav Hama goes on to list several other acts of hesed—gemilut chasadim—exemplified by Hashem in the Torah. God doesn’t just instruct us to be kind, generous, and compassionate, but he steps into the human story to show us how.

Rav Hama places this scene by the oaks of Mamre just a few days after Abraham’s circumcision in Genesis 17, when the old man is still recovering from the painful procedure. The Almighty visits Abraham at this moment to show us how to care for the sick among us, those who are ill in body and soul, just as he provides the example of caring for the impoverished and vulnerable (the “naked”) and the bereaved, as Rav Hama goes on to mention: “The Holy One, Blessed be He, comforts the bereaved, as it says, ‘And it was after Abraham died that God blessed his son Isaac…’ (Gen 25:11), so too shall you comfort the bereaved.”

God shows up in the midst of our human neediness and if we seek to follow his example, we’re likely to run into two obstacles.

In some cases, we might be tempted not to show up at all, even if we care, because we just don’t know how to act around those who are suffering and so we allow ourselves to avoid them.

In other cases, we might show up but say too much, particularly when we visit the bereaved or those facing life-threatening illness.

We try to cheer up the afflicted, or provide superficial assurances. We tell mourners that their loved ones are in a better place, or that God had a better purpose for them. We regale the dying with tales of miraculous healing (which might well be true), when they may already be focused on preparing to leave this life for the next.

Hashem’s example of simply showing up at Abraham’s tent door and saying little will serve us well as we visit the sick and comfort the bereaved. Knowing the power of simply being present for the suffering frees us from the need to figure out what to say.

And there’s another lesson here, based on another reading of the opening scene of Vayera, one closer to the text itself.

In this reading, Hashem shows up at Abraham’s door not as a comforting visitor, but as a wayfarer seeking hospitality. He shows up with two others not to provide gemilut chasadim but to receive gemilut chasadim himself.

The passage focuses on Abraham’s generous welcome to these three strangers (Gen 18:3–8). God reveals himself to Abraham after Abraham washes his feet and feeds him a lavish meal. We’ll miss the impact of this story if we think of hospitality as a matter of tea and cookies out on the veranda. In Abraham’s world, hospitality to a stranger could be a matter of life and death. Roadways and trails were dangerous, spied on by bandits and marauders, with great distances between watering spots and sources of food. Strangers were looked upon with suspicion, and even those who intended them no harm might find it best to maintain a safe distance—just as we’re tempted to do with those we label the “homeless” around us. Back then, travel was dangerous and hospitality a great mercy, and the Lord shows up as a stranger in need. He reveals himself to Abraham as he reaches out in simple compassion.

Messiah Yeshua may be building on this passage in the Torah in his striking portrayal of how he reveals himself to us. He begins, “When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on his glorious throne,” and goes on to describe his judgment of the nations, separating them like sheep and goats to his right or to his left (Matt 25:31–33).

Yeshua continues,

Then the King will say to those on his right, “Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you clothed me, I was sick and you visited me, I was in prison and you came to me.” Then the righteous will answer him, saying, “Lord, when did we see you hungry and feed you, or thirsty and give you drink? And when did we see you a stranger and welcome you, or naked and clothe you? And when did we see you sick or in prison and visit you?” And the King will answer them, “Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me.” (Matt 25:34–40)

Vayera—the Lord appeared to Abraham to support him in his recovery from bodily affliction, and we should do the same for the afflicted around us. And the Lord also appeared to Abraham as a stranger needing help, just as he might appear to us if we have eyes to see. In this appearance story Abraham provides the example, watching at the door of his tent for an opportunity to practice gemilut chasadim, gifts of kindness, to those who need them most. As we are watchful and ready like Abraham we may well encounter Messiah Yeshua himself.

Scripture references are from the English Standard Version (ESV).